Making the Video That Made Gorillaz

Plus: news.

Welcome! It’s time for a new Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Glad you could join us.

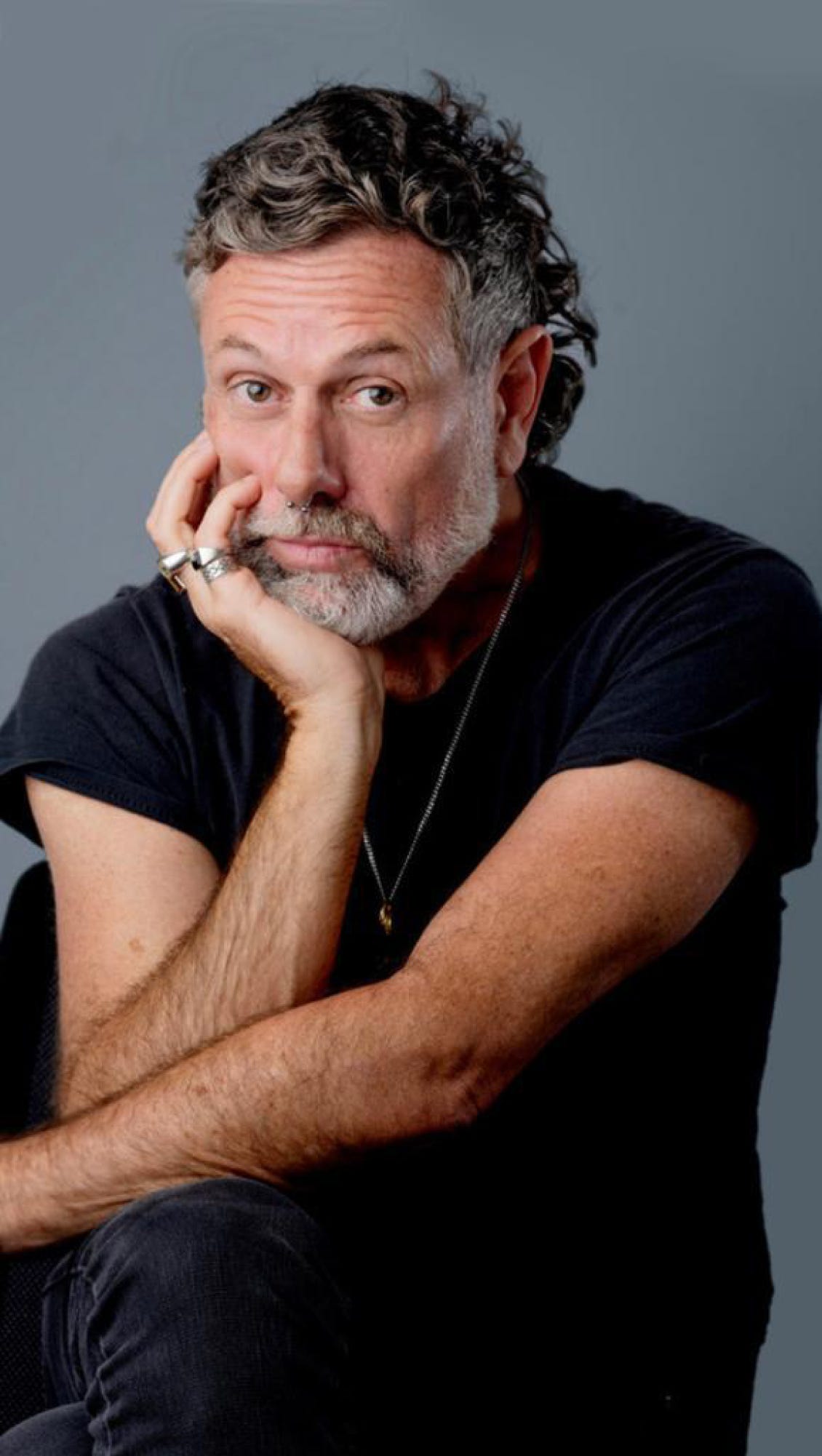

Today’s lead story is a little bit different. Last summer, Sophie Kuebler of NSNS Magazine pitched us an interview with Pete Candeland — whose videos for Gorillaz tracks like Feel Good Inc. and DARE need no introduction. He spent almost two decades as a Gorillaz director, animator and more. (Presently, he’s at Laika.)

The two of them dove into his process and origins, and particularly into one of the century’s most recognizable music videos: the one he did for Clint Eastwood (2001). Candeland rewatched it for the first time in years, pausing to explain the decisions and influences (and even the mistakes) that made it what it is.

With that, here’s our slate:

1) A conversation with Pete Candeland.

2) Animation newsbits from around the world.

Now, let’s go!

1 – “The noodle of it all”

I meet Pete Candeland at a bar in Mexico City. He directed music videos for Gorillaz, he tells me. I think he’s joking.

“The band?!” I ask. “And your last name is Candyland?”

“It’s with an ‘e’ instead of a ‘y,’ but yes, it is,” he says.

As a Gorillaz fan, I’m stunned. I’ve never heard of him.

I Google him the next day — he isn’t kidding. But, apart from a few IMDb entries and a couple of photos, I can’t find much about “Pete Candeland.” When I ask friends who work in animation, they call him an “OG.” One of the “most influential animators.” I get curious.

A few weeks later, I meet him again to chat about his work over dinner. He’s an open book. I leave knowing much more about animation, the industry and directing as a whole. I can’t help but schedule another meeting.

What comes next is a search for an artist and his influence — on a generation, and on an entire era of animation and pop music.

At a moment when pop culture stood on different pillars than today — the internet was rising against TV and print, Napster was rethinking music distribution and the hype of the new millennium was in the air — young people were looking for songs they could connect to. Songs that felt like the future.

Following up his success in Blur, Damon Albarn partnered with artist Jamie Hewlett (Tank Girl) on a fresh idea. Gorillaz would be their animated band, its music credited to slick, fleshed-out, anime-inspired characters who starred in the videos. 2-D would be its frontman, with Murdoc, Noodle and Russel behind him. Other bands had released animated music videos, but not like this.

Doing it right would take a director willing to push boundaries.

Pete Candeland was originally from Sydney, where he’d started as an intern at Disney in his teens. Then he moved into the ad world, finding his first real success with a Coco Pops commercial. Its mix of 2D and CG animation was innovative — it gave him a name. Like Albarn and Hewlett, he was trying something fresh.

When I ask Pete how he got the Gorillaz job, he tells me, “Jamie. He saw that Coco Pops [ad].”

The band’s first EP landed in 2000, featuring the song Tomorrow Comes Today. A few months later, the single Clint Eastwood hit, and Pete’s music video for it changed everything. It was an adventurous use of 2D characters in a CG world.

I speak to Belinda Blacklock, a longtime friend of Pete’s and a producer who worked back then at Passion Pictures, the animation studio behind Clint Eastwood. “I think those videos were really groundbreaking, especially when he moved them from 2D to 3D,” she says. “3D wasn’t like it is today. I remember at Passion Pictures at that time the 3D department was like eight to ten people and the 2D department was a whole floor.”

Pete was already one of those directors willing to push boundaries, Belinda tells me. Someone with a different approach. “He really thinks about things from a live-action perspective, even though they’re animated. That’s kind of become his signature style,” she says. “And then he moves the edit around a lot … he tends to tweak and tweak and tweak until it’s just right.”

Clearly, there’s more to discover here.

When I next meet Pete, we’re on a bus from Querétaro to Mexico City. During the ride, he gives me the complete anatomy of the Clint Eastwood video, that first classic. I still can’t accept that so few fans know his name, and I want to hear everything — from the beginning.1

Sophie: What, for you, is the definition of animation?

Pete: Animation is bringing something alive. For me, it’s about bringing characters alive. It ultimately is bringing a story alive — but first is characters.

Sophie: And how did you get into it?

Pete: I was in Australia, and I was like 17. I was always drawing and loved art, and looked up to this guy [at school] called Sinduh who did amazing graffiti. I wanted to be a graffiti artist like him, and that’s how I started to draw — I was copying his stuff.

After high school, I went to graphic design school. That didn’t work for me at all; I only stayed for about three months. I got into animation because I got an in-between test at Disney. I had no idea what it was, but that was how you started back then.

I used [the job] to earn money and fuel my skiing habit, ‘cause I wanted to be a skier at that time — or just to ski and do nothing. The more I got into the filmmaking part of animation, the more I started to love it and grow.

Sophie: You must have had things that influenced you, stylistically. You often talk about clouds, for example, and the sky.

Pete: That’s a little bit later in my [career]. Over the years of work you do, you get all these tentpole moments of realization that you love something. One of my first big tentpole moments was Natural Born Killers. When that came out, I went, “That’s the type of thing I want to do in animation.” Really, it didn’t matter if it was in animation or not, but I kind of got stuck in animation.

Then came things like Guy Ritchie and Tarantino, who were really big tentpole influences for me. And I was in a kid’s world of animation, having to do Disney stuff, frustrated because I wanted to do this ultra-cool stuff. I found myself in a bit of a dilemma.

The clouds are a tentpole within my development in the way that I light a scene and create its visuals. Spending such a lot of time in London, I noticed that the skies were absolutely amazing, and they gave personality to the city at different times of day, or in different weather. London changes massively from the bright, sunny day in the summer to the cold, winter, gray days. And all of the personalities in between are dictated by the sky, changing the mood of the place.

[Artist] Daniel Cacouault and I would talk about skies and lighting bringing the personality to a scene. I would often start with the sky to figure out, “Well, what’s the energy that I want?”

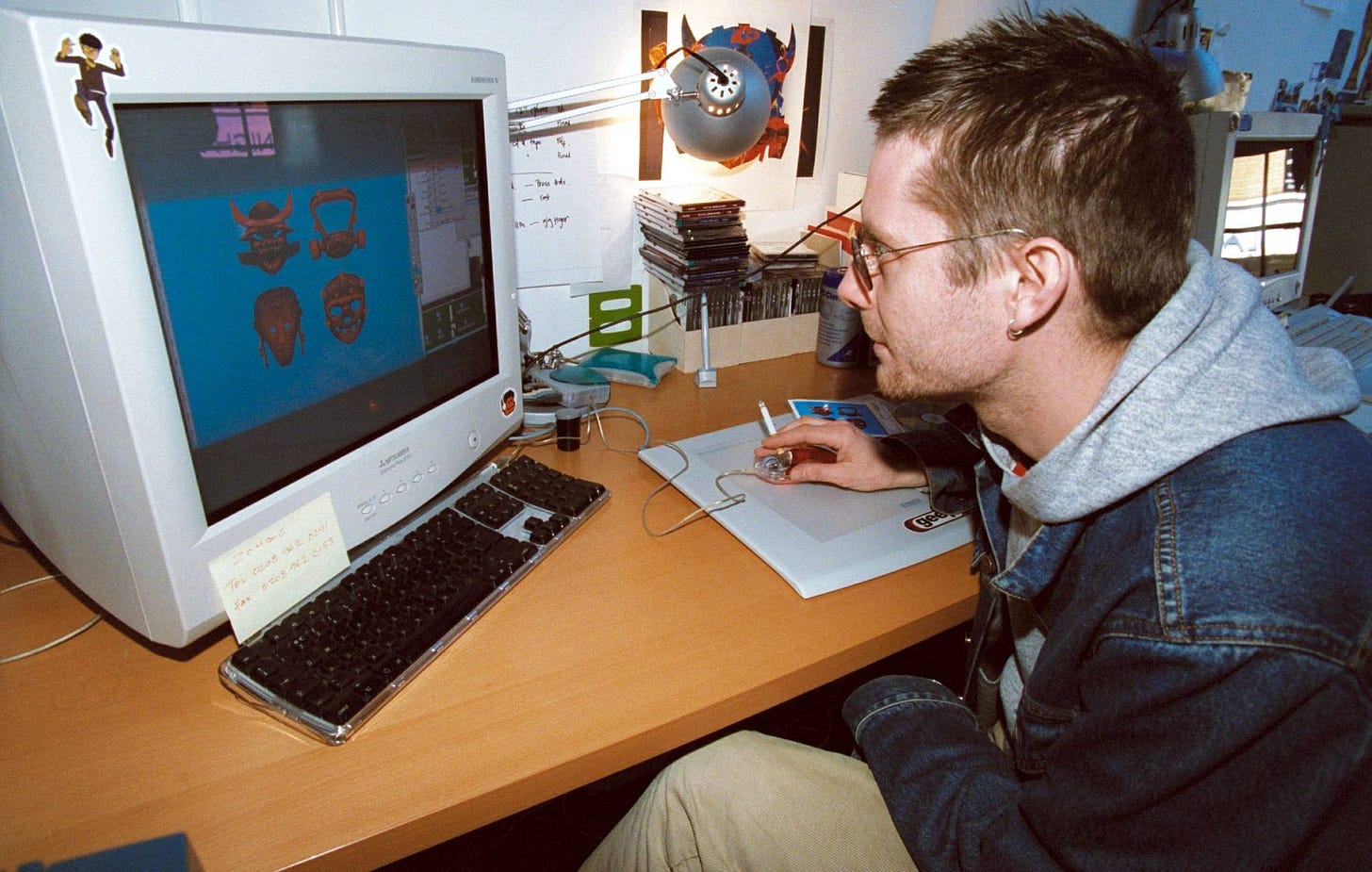

Sophie: Let’s imagine it’s the year 2000. You’re sitting in London at Passion Pictures. Did you have a room, a studio?

Pete: We had an apartment. I would turn up at like 5 o’clock in the morning, open it up. I was working in the living room at a desk with my drawing board on it. On the other side of the big table was my assistant. Then we had the kitchen. Upstairs was where all the assistants and coordinators were working.

It was attached to Passion Pictures, the big animation studio. We got lucky: we rented the flat next door. It was called the “Gorillaz flat.” At the time, it was easy and comfortable in there, while the big Robbie Williams thing and Tim Hope’s Coldplay stuff were going on next door.

From that 5 o’clock until 9 o’clock, I would get all of my animation done — the primary amount of my drawing and animation and ideas. Then, as people started to turn up, that would start taking my time. Working with them and helping them stay on track and directing them.

Sophie: When was the last time you saw the Clint Eastwood video?

Pete: A long, long time ago. Must be over a few years — more — since I saw it fully, I think.

I can remember it pretty well, though. I can remember like every frame, because I directed it and animated most of it. I didn’t sleep for almost three months doing that. So it’s etched in my brain.

Sophie: Did you have a story for it first?

Pete: For this, we didn’t. It was me and Jamie, coming up with the graveyard idea. Jamie and I learned we had lots in common, from magazine references to movie references, zombie references and general cultural taste of stuff. He started the storyboard with the first half and set it in a graveyard. That triggered me into the zombie idea with the gorillas, and how to go about doing that second half.

So, it was this combined effort. I just knew and understood, technically, how we were gonna go about bits and pieces. In order to balance out the big highlights, I had to thin out some of the work at the front so it was simpler — and use some CG for the first time — to then allow us the freedom and the capacity to do the bigger dance numbers at the end.

Sophie: Why put the big dance number at the end?

Pete: You always try to build entertainment almost like a ladder — or steps — going up to a climax. Like a little story. You want to keep people involved by giving them just enough to want to know what’s going to happen next.

In a short video, it’s about what comes in the next 20 seconds, and then the next 20 seconds, and then the next. It’s an escalating ramp-up of interest, and sometimes a ramp-up of activity and richness of imagery.

So, I was working with that nice, clear, linear arc. That meant a lot of the attention went into the high-energy dance at the end, contrasted at the beginning by a slow, gradual introduction of the band that then escalates — hopefully, at the right times.

It just felt quite instinctive. I don’t know if there was a specific place I got it from, but I’d been directing for about two years on commercials and, before that, I was an animator. I think the knowledge must have seeped in through conversations with directors, with other animators or just through my own observations.

Because you learn about pacing as a storyboard artist. I was always able to pin my storyboards up on the wall and “watch the video” in my mind. I’d see where the peaks were and where the troughs were — the places where it gets a little stagnant. Nothing new is happening; nothing’s escalating. And, if it was a trough, I’d try and fill it in and make it more interesting. That’s something I still do now.

Sophie: Okay, let’s watch the video…. Why is that text in Japanese (0:07)?

Pete: That’s from Jamie. I think he had just come back from Japan, and had a big influence from Japan. And it was the noodle of it all — I think he’d recently come out of designing and figuring out Noodle, and how she was gonna look.

Sophie: What were you getting from Jamie art-wise?

Pete: What Jamie’s giving [me] is a model sheet. A drawing of what he wants Noodle, Murdoc, Russel and 2-D to look like on the front and on the side.

So, yeah, we’re introducing each of the characters individually… and we can stop there (0:27). I want to show you a mistake that lived on.

I animated all of this. We were doing those movements in a really different way to usual, which was in After Effects. The technology was new and we got to play with it. But the mistake is that 2-D’s got two bags under his eyes.

That’s a comping problem. I only drew one as a separate layer, and then the compositor accidentally put two in, duplicating it. I never noticed it until we finished the video. Then we kept two bags for other times, occasionally.

These were simple executions of trying to make a band look like they’re playing the instruments and singing (0:38). The lip sync’s quite good in this. And then I was bringing in effects in comp.

If you stop there (0:58), that’s the first “step,” to me. We’ve introduced the band in a really simple way, and now [we] want to step it up. Because the music is stepping it up, we’re going to visually step it up as well.

So, we’re bringing in a new character. The idea is that Russel falls asleep — he’s narcoleptic. Then he’s possessed by this ghost who comes out of his body. He’s way more dynamic: he’s moving around the camera and the scene a lot more than the other characters were. He’s got all these different poses, and he’s kind of taking over.

Coming along with the introduction of this character is all the static that’s running through him, which is a bit of a step up in energy. Recorded static off the TV — you take that as one of the layers and multiply it into your drawing. I was trying to figure out, “What’s my unique idea, or what would make Del the Ghost Rapper different?” And it was to put static through him.

This is the first time we’re introducing CG (01:25). The technique is a step up from the simple opening. We’re going, “Okay, we’re gonna start playing now and show you some things.”

Sophie: Which parts were CG?

Pete: The ground cracking open is CG. The light coming up and out of the ground is all volumetric. It was super hard to do at the time.

We’ve escalated I think two steps now, because the CG tombstones are coming up (01:41). We started off on a really simple, white background. Brought him in, took it up one step. And he’s brought another element in, which is the CG transformation of the background. Then these camera moves start to get much more elaborate (01:50). The layers of visual richness get a bit bigger.

[2-D is] hand-drawn by me, and all of that [behind him] is CG (02:06). That was a very unique moment in animation when no one was really doing that. We’re comping hundreds of layers to get this type of stuff.

Sophie: Why was no one doing that at the time?

Pete: The technology was new and I was one of the first to notice a way to do it.

People mostly were building CG, and they were trying to make the [characters] in CG. I wanted to keep my drawing in CG. So, I’d put a fake CG screen inside the CG scene, and I’d project my drawing onto that poly. It’s something I still use all the time. A lot of people started to do [it] after this video.

Now, we’re breaking all the CG (02:14). We’re playing with it — we’re discovering how to make it at the same time. We’re taking it another step up.

I was talking about a tentpole earlier — what I loved was using all the techniques and ideas that other filmmakers were doing in live action, and bringing those into animation. So, you see the gorilla get up multiple times. You repeat the footage (02:18). I was loving those techniques from The Matrix.

Then Murdoc runs away (02:29), but I didn’t have the energy to animate it. I just did stills, and he fades.

Sophie: I love the shoulder movements (02:44).

Pete: That was all based on Thriller. At the time, I watched and watched it, and I would turn it off and draw from what I remembered. Rather than copying, I used my memory. This is a method I still use. To me, that became important, what I remember… because I believe this is what other people will remember, too. And I remembered the slide and the clap. Those became the most iconic parts for Clint Eastwood.

By this time, we’re bringing all the elements together (03:00). You’ve got multiple gorillas, you’ve got the tombstones, you’ve got 2-D — you just had Del the Ghost Rapper whisper in his ear.

Then this Noodle stuff (03:20) was all playing with techniques that I loved in The Matrix. This [video] was me playing a lot with “rock and rolling,” we call it. Taking the footage, playing it forward and then rolling it backwards, and finding a rhythm. Here, I have her run and then play it backwards and forwards, and repeat it, and get more rhythm out of the animation, so it sits with the music.

Sophie: Oh, this here is totally The Matrix (03:32).

Pete: What I was doing there, when she’s kicking, was animating the same shot from different angles. People hadn’t been doing that in animation. It’s like using camera one, camera two and camera three at the same time on set. It would take me a long time, but I’d animate “camera one,” then “camera two,” then “camera three,” and then I’d be able to cut it like live action.

By the end, we’re taking everything back down to its simplest form again, like the beginning (03:38).

I was trying to animate the last shot on the last night. Everyone was pissed off with me because I couldn’t get anything that I liked. So, we took some still drawings into composite and made it up in the last hours before delivery. It’s when the zombie gorilla becomes a skeleton (03:43). That was meant to be animated, but it’s not. It’s just a series of cheats.

Sophie: You told me that you found the animation style for the video by accident, because of the limited budget.

Pete: Yeah. You want all the pieces coming together in the biggest way that you can afford, right? I wanted to multiply the gorillas and make a big dance number. There’s lightning going on at the same time; Del is coming into the shots. It’s really busy and big. I kind of knew what we’d need to spend. In order to afford that, I tried to make the beginning cheap and simple.

It’s less expensive, and we were doing less work — but that doesn’t make it less cool or good. I was using a lot of anime and manga techniques, where the classic thing is you’ve got a still face, but the hair is blowing in the wind. I used to love that — I was completely captivated at the time by those ideas, that world of animation. They were using ultra-cool poses, and the character didn’t need to move because the drawing was telling you everything. All you needed was a little bit of life.

So, I was using that. For example, not having enough money meant, for Murdoc, I was only able to animate his fingers playing the bass. For 2-D, I could only animate the lip sync. But those were the most important parts of the characters.

Sophie: So you kept it as the style.

Pete: I started to recognize that this was a technique that I loved for the animation. Because it was easier to do, and because it gave a signature look and feel to what we were doing, which wasn’t over-animated.

I have a big issue with over-acting and over-animation, so I would play it the other way — I’d under-animate everything. Make it as simple but as cool as possible. It started to become a signature for Gorillaz, and the way that I would work. It was the opposite of Disney.

With that video, all of those ideas that we’re seeing, I had been building up in my head for like a year or two, frustrated at Disney. And then it all poured out. For me, it was cathartic.

I started taking those ideas and techniques into other videos and into CG — which is quite unusual, because CG is built to animate and move everything. I would build something in CG but keep it really static, and just move the parts that told the story. The most important parts; not everything.

That was a slow evolution of learning what you need to do to make something cheaper, loving anime and then realizing that, if I work on it right, it’s cooler.

Sophie: Belinda told me that you started using a different type of editing, a live-action process. Can you explain that a little bit?

Pete: With Clint Eastwood, I was so excited to see my scene against the music that I would go down to the edit suite. It was a digital changeover; we weren’t shooting on a rostrum camera anymore. All of my animation was digitized and we could look at it really quickly. I was like, “This is amazing!”

Loving the editing process, I noticed most animation directors didn’t work in the edit much. I didn’t understand why because I wanted to see my animation cut in with the music. An animator would get the length of time that their scene would last, and that’s what they had to draw. It could be two-and-a-half seconds, or five. That would get assembled in an edit. The editor was not a creative editor at all; it was just assembling.

With [editor] Kevin [McDonald at Passion Pictures] I learned what we could do in the edit. I’d be sitting with him and I’d get him to shift the timing left and right. With one scene of animation that lasted three seconds, I could suddenly make it 12 seconds, because I would repeat it and play it backwards or forwards, timing it to the music. You’re able to create a lot more footage than you’re actually drawing. I went, “This is animating live!”

That’s how I did most of the back half of Clint Eastwood — that was all built in the edit. The edit suite became my home base. I still believe in it completely.

Sophie: What did you add to your toolkit through the Clint Eastwood video project?

Pete: Quite a bit. After that video, my general attitude towards my own work was to never do the same thing again, technique-wise. What I learned from that video, I took into the next one, but would always build on top of it with another technique idea.

Working on Gorillaz, I had the freedom to make all the choices of how to do it, with very little oversight. That was the attitude that got me into live action, got me into more CG, into all the diversity that I got out of Gorillaz. It was from bringing a bit of invention to the first one, and then wanting to bring invention each time to the next ones.

By doing that, I got to learn and make loads of mistakes, but ultimately get a really full look at filmmaking. I just got lucky.

Sophie Kuebler is a sound designer and sound editor specializing in games and post-production. As a writer, she shares stories and conducts interviews on independent platforms, as well as through her own projects NSNS Magazine and Sophie Sound.

2 – Newsbits

We lost cartoonist Jules Feiffer (95). Alongside his print work, he spent time in mid-century animation — writing and storyboarding the brilliant Munro (1960), the first cartoon produced outside the States to win the Oscar for animated short.

I Just Wanted to Say is a new Japanese film based on a children’s book, and it’s very nice. Check it out on YouTube.

Starting this month, Hayao Miyazaki’s personal Citroën 2CV will be displayed at Ghibli Park in Japan. “We would like to cherish it as a treasure of Ghibli Park forever,” said the governor of Aichi Prefecture, the park’s home.

In France, first-year animation students at École L’Atelier created Apollonicon — a fun, novel film that put each animator in charge of a few seconds.

Nezha 2 is a few days away in China, and ticket pre-sales are strong. By the 24th, they’d already passed 76 million yuan (over $10 million). The original Nezha is the country’s biggest animated film to date, so all eyes are on this one.

In America, the Oscar nominations were announced. Flow nabbed two — The Wild Robot, three. Elsewhere on the list, we find the new Wallace & Gromit movie and In the Shadow of the Cypress. See all the nominees here.

Also, don’t miss the live reaction of Flow director Gints Zilbalodis (Latvia) to his film’s nominations.

Moana 2 has earned more in South African theaters than any other animated film. The Citizen reports that it’s also “the highest-grossing animated film of all time in East and West Africa.”

My Life at 24 Frames per Second, the manga autobiography of Rintaro, is out in Japan. But it was published first in France. The largest Japanese newspaper ponders what that means, and praises the book, in an English article.

Lastly, we wrote about some of Tissa David’s classic animation.

Until next time!

The interview between Kuebler and Candeland has been edited for flow, clarity and length, and contains additions from later emails and exchanges.

Completely awesome! Thanks for including the gifs -it was neat to see many of the specific scenes discussed.

This is such a great interview— it's col to hear that a lot of this was just playing and trying things out; it really was the only think that looked like this when it came out. Super cool