Welcome! Thanks for joining us. We’re here with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is what we’re doing today:

1) Watching the Zagreb cartoons in 2025.

2) The ongoing Nezha 2 boom.

3) Newsbits in animation.

Now, let’s go!

1 – “An atmosphere”

Something exciting happened in 2022. Quietly, a collection of restored cartoons began to appear on YouTube. Cartoons made in Zagreb during the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. Products of the Zagreb School of Animation.

This was a big deal. Like we wrote at the time, “Many insiders have long admired and prized the cartoons of the Zagreb School. For decades, they’ve been rare — or stuck in shabby quality. But that’s finally changing.” The School was a lawless, hyper-modern inheritor of the UPA revolution: critics and artists loved its films. Now, they were back in beautiful quality.

Only some of them, though. The official Zagreb Film: The Art of Animation channel had lots of holes in 2022. But it wasn’t done. Restorations have continued to pop up as recently as January of this year.

Soon after these films reemerged, we did a brief intro to them. Years have passed since then — and the collection is much, much larger. It’s a treasure trove that’s always expanding. So, today, we’re revisiting this work and remembering what makes it so special.

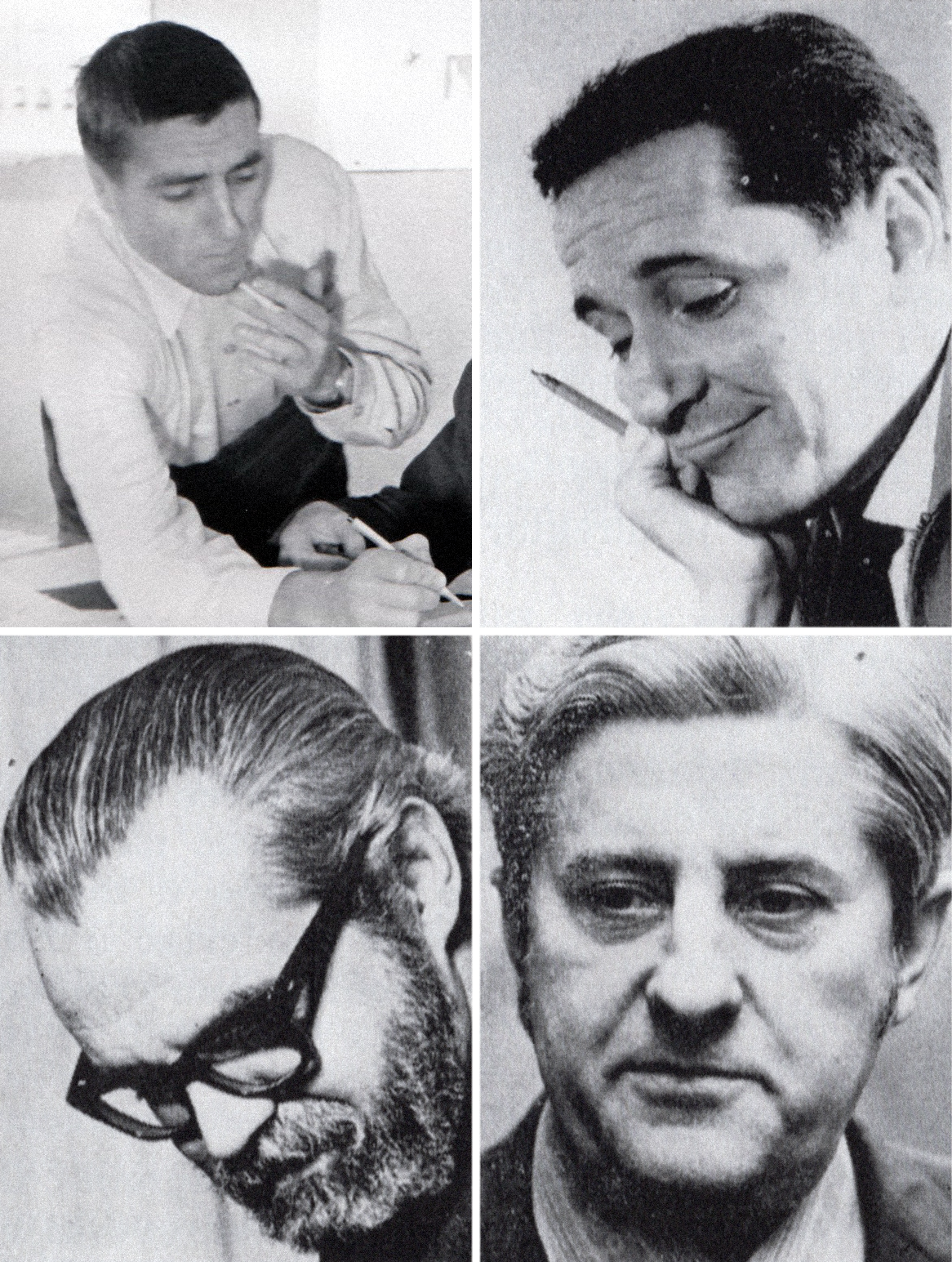

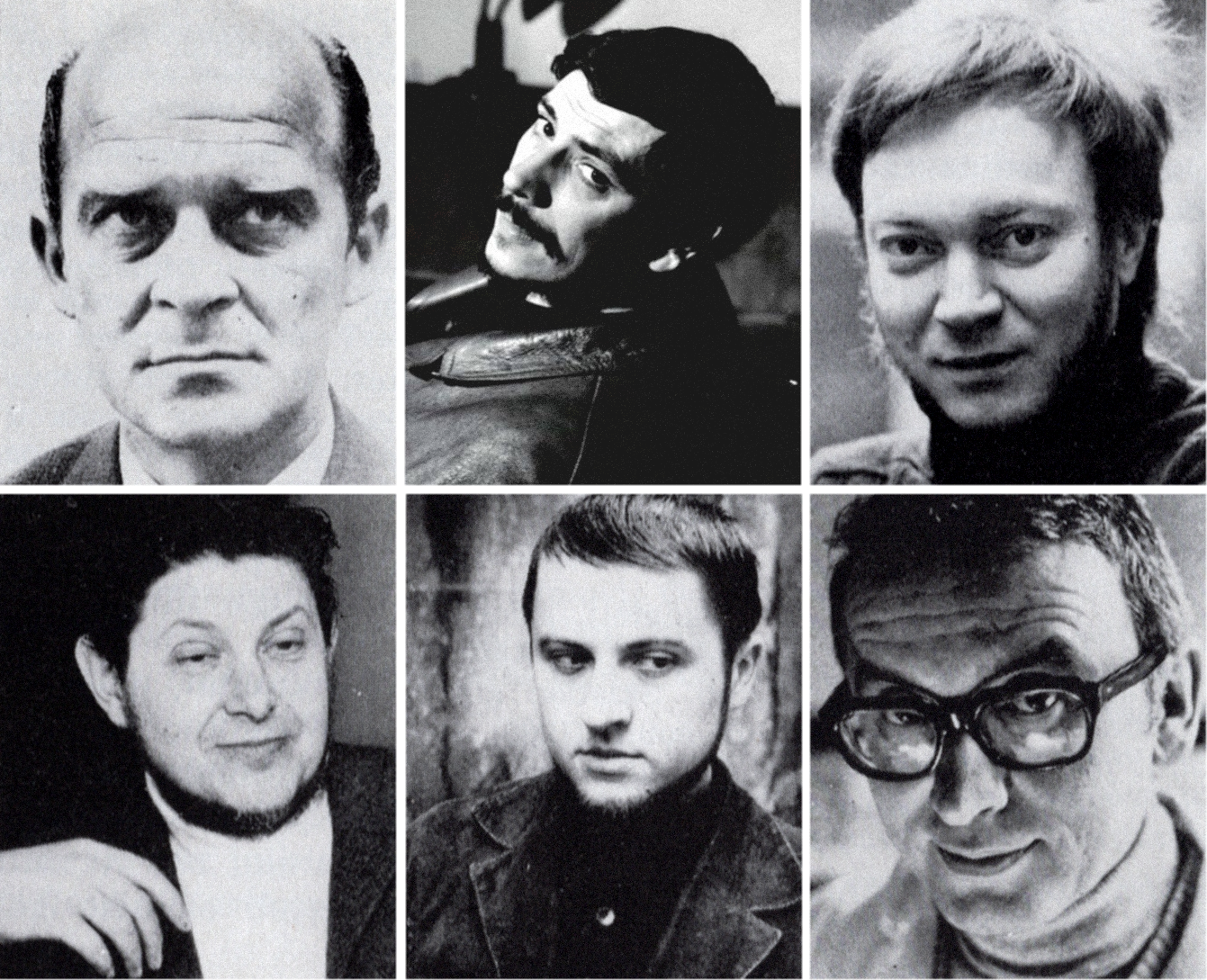

People have attempted to define the Zagreb School since it began in the ‘50s. It’s a fuzzy thing. In Yugoslavia (an ex-country), a bunch of artists worked in the city of Zagreb at the studio Zagreb Film, on Vlaška Street. It was the hub of Yugoslav animation — and everyone there brought a different style and philosophy.

“The Zagreb School, or more precisely our studio, is not an artistic academy or boarding school,” said Dušan Vukotić, the group’s leader. “It is above all an atmosphere, in which individual potentialities are maximally expressed.”1

It favored variety. Take the duo Aleksandar Marks and Vladimir Jutriša — one a cartoonist, the other a former railroad employee. Their film The Fly (1966) is a gem of stark, psychological horror. Yet they also gave us A Modern Fable (1965), a very funny satire on people’s treatment of nature in the 20th century.

Neither film looks or feels much like the other. And both are pretty far removed from Vukotić’s own Oscar winner Ersatz (1961), which later inspired the Worker & Parasite joke from The Simpsons.2 Yet all three have subtle things in common. They defy the Disney tics of design and movement, for example — and they tell stories for adults about modern concerns (alienation, consumerism, industrial society).

It was a fresh approach. In the words of a Zagreb Film manager:

From the very beginning the Zagreb School abandoned the concept that the cartoon is only for children or is simply a curtain raiser.

A film may be, and should be, art. The cartoon film is art par excellence. The Yugoslav film deals primarily with human beings and attempts to portray them through modern graphic expression.3

In addition, The Fly, Ersatz and A Modern Fable are all wordless, which was common for Zagreb cartoons. “We are a country whose language is spoken over a limited territory,” explained animator Zlatko Grgić, “so we have had to formulate a universal language. … We have therefore had to resort to a kind of mime.”4

The ideas of the Zagreb School first solidified in the mid-1950s. Back then, Yugoslav cartoons were close to non-existent — but Dušan Vukotić led a small animation team in an apartment. Pulling from the modernism of UPA and Jiří Trnka, they did a series of ads around ‘54 and ‘55. According to one historian:

Since material resources and particularly the availability of cels … were limited, the process of “reduced animation” was discovered. Some [advertising] films took an unbelievable eight cels to make, without losing any of the expressive movement a large number of cels usually required. … Writers, architects, sculptors and painters lent a creative hand whenever needed. The cartoons took on a daring, avant-garde surface.5

It was a starting point. By 1957, Vukotić and his team were set up at Zagreb Film, and he was explaining their theories to the press. Disney’s style had run its course, he argued: the “strictly idealistic” fairy tales, the fixation on realism, the use of only round shapes in the characters.

Vukotić called for “new, modern” themes, and new forms of design and movement — beyond the circles, the ovals and the “soft and very flexible animation.” Although he praised Disney’s advances, he was fiery in his attacks on the studio’s style. He described it as a commercial “formula” that:

... does not require particularly great drawing skills, and what is perhaps more important, the time spent on creating a frame of such a drawing is half that of a free graphic solution of modern cartooning, which does not carry any laws and requires from the [draftsman] more time and more artistic knowledge.6

The following year, Zagreb Film’s cartoons took over at festivals. They weren’t like Disney’s, or even much like UPA’s. The ‘58 Cannes screened films like Happy End, a dark, artful and gag-free meditation on the end of the world. It’s gorgeous, and it flows without hard cuts for 10 minutes. Joining it at the event were Alone, On a Meadow, Scarecrow, Abra Kadabra and Revenger.7 Not all were classics, but something new and different was happening here.

Unique artists were behind this unique work. Happy End came from a live-action director, Vatroslav Mimica, who’d turned into a leading poet of the Zagreb School. Meanwhile, designing films like La Peau de Chagrin and The Man and His Shadow (both 1960) were avant-garde painters from Yugoslavia’s EXAT 51 movement.

One of those painters, Vlado Kristl, was an unstable virtuoso who lasted just a few years at Zagreb Film. “Kristl is a man whom I appreciate enormously as an artist and hate terribly as a person,” said Zlatko Grgić. He was paranoid and delusional, but “the most superior, incredible” cartoonist. You see it in Kristl’s film Don Quixote (1961), the furthest-out of any Zagreb project, and among the most famous.8

There were still other key names in the School. Nikola Kostelac (Opening Night) was an architect before he got into animation. Boris Kolar was a print cartoonist first, and his graphically brilliant Boomerang (1962) and Woof-Woof (1964) are some of Zagreb’s best-looking cartoons of the ‘60s. Pavao Štalter was classically trained as a painter, and had planned to be an art restorer, but he gave us films like The Masque of the Red Death (1969) instead.9

All of these artists fed each other. “It was constant brainstorming, a constant exchange of experiences … Each sought their own individuality, and yet they shared a common spirit,” said Mimica. His own Typhus (1963) is a visual stunner in the expressionist woodcut style. Its design and animation were the work of Aleksandar Marks and Vladimir Jutriša — for whom Mimica wrote The Fly.10

That habit of cross-pollination helped to create Zagreb Film’s major hit: the TV series Professor Balthazar (1967–1978), dreamed up by Zlatko Grgić. It’s the School at its most accessible — full of charm, light humor and fun cartooning. Many hands touched it.

Professor Balthazar isn’t much like The Masque of the Red Death, but its lead character was named by Pavao Štalter.11 The cynicism and abstraction of Boomerang aren’t present, but Boris Kolar was a main director and animator here. It’s not a piece of hostile avant-gardism like Don Quixote, but one of Don Quixote’s animators, Ante Zaninović (The Wall), was a star artist on it.

Still, Balthazar is pure Zagreb in its weirdness and creativity — and in its brazen anti-realism. That third thing was true of every Zagreb cartoon, no matter its style. As Vukotić once explained:

Since animation is not burdened with the ballast of physical laws, it is not a slave to literal reality and does not imitate life, but interprets it. And because of this, the first question I ask myself for a script is: can this text be filmed with live actors without any substantial changes? If the answer is yes, the script in question is not suitable for an animated film — in other words, what can be shot with actors is senseless to draw.12

A few factors underpinned the Zagreb School. For one, Yugoslavia was communist, but not Soviet: the arts were funded with few restrictions. They weren’t funded very well, though. Just as important to the School was its tenacity, and its desire to push boundaries even when the money and equipment were bad. The cartoons it aimed more at the masses (A Modern Fable, Balthazar) tended to be strange, too.

“Our studio has long lived on moral victories,” lamented Aleksandar Marks in 1965, “but not on material ones.”13

Exploring the Zagreb Film channel today, you find oddities that are hard to explain logically, let alone economically. It’s fascinating to look at 1x1=1 (1964) — but even a leading scholar of the Zagreb School dismissed it as “a complete puzzle.” Referencing Worker & Parasite to ding Zagreb cartoons is played out, but The Man and His Shadow nearly lives up to the stereotypes, despite how eye-grabbing it is.

The School could be inscrutable at times. In its stories and visuals and more, it focused on rebellion. It was anti-tradition and anti-cliche — which took it to unexpected places. You hear that in the bizarre audio of its films. Like one critic noted:

… their use of sound is both original and remarkable. Their music is never mickey-moused, but is used as music is in ballet. All musical genres are utilized — including jazz and modern idioms. … Yugoslav composers avoid most of the usual cliches, such as obvious quotation from the classics … The visuals [of Alone, for example,] are surrealistic, and on the soundtrack, in addition to such real sounds as those of typewriters, there are synthetic sounds — some are produced electronically; some by running tapes of music and singing at velocities which make the sounds high and squeaky; and some by drawing on the soundtrack à la McLaren. … Although some of these effects are far-fetched and would-be, most of them click.14

That was how the School operated in general: it tried things. Many of them ended up as one-off experiments. Some of them only sort of worked — or didn’t work at all. These artists saw and acknowledged plenty of problems in what they made. Mimica called Happy End “very dear” to him, but he felt that the amazing-looking Typhus was a bit of a misfire.15

So, very imperfect. And yet perfection wasn’t the point. In Zagreb, cartoons were powered for decades by mad invention and the charge into the unknown. The results were inspiring then — and they’re inspiring now. We’re lucky to live at a time when the School’s successes, failures, delusions and discoveries are freely accessible to all.

2 – Animation news worldwide

2.1 – An update on Nezha 2

The historic run continues. We wrote last Sunday that Nezha 2 was breaking all kinds of records since its release in China. This weekend, after 10 days in theaters, the film passed $1 billion at the Chinese box office. No movie, live action or animated, has hit that number in one market until now.

And it isn’t done. Nezha 2 shot past 8 billion yuan (around $1.1 billion) this weekend, with a reported 160 million tickets sold. That beats every previous record-holder in the country. To give a sense of the scale: Boonie Bears is one of China’s largest movie franchises, and it reached 8 billion yuan last month — after 11 years and 11 theatrical films.

Forecasts keep changing, but the latest predicts a total above 12 billion yuan for Nezha 2, or somewhere north of $1.64 billion. If that happens, the film will rank in the box-office top three for animation worldwide — bumping Frozen II ($1.45 billion) to fourth place. Depending on Nezha 2’s momentum, Disney’s records for the Lion King remake and Inside Out sequel may be at risk.

In China, the film’s launch has come with reports of huge lines, sold-out showings and the conversion of a “2,000-seat auditorium” in Henan into a theater, where the film screened multiple times per day. (There’s video of that last one.) Chinese news coverage has focused a lot on the 138 companies in the credits, some of them very small teams of animators who worked on bits and pieces of the film.

Also, this week, a rumor spread on Chinese social media that America’s government had banned Nezha 2 for reasons of “national security.” The press roundly debunked that rumor. As it stands, the film should be out in the States on February 14.

2.2 – Newsbits

We lost Joe Hale (99), a Disney veteran who worked on Sleeping Beauty and many more.

In America, a new campaign supports animation workers affected by the Los Angeles fires. It’s called AnimAID, and Cartoon Brew has details.

In India, Vaibhav Kumaresh of Lamput fame reminisces about the Simpoo Singh cartoons, a defining early success for him. See the series of posts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

One of China’s top imported shows last year? Peppa Pig, which remains very popular in the country.

In America, back in the 2000s, an attempt was made to turn Mike Mignola’s comic The Amazing Screw-On Head into an animated series. Now, a YouTube documentary tells that story and shares the show’s pilot in high quality.

The Wild Robot took nine categories at the Annies in America. Meanwhile, Adiós (trailer) won among student films — well deserved. See the full list via Variety.

In Japan, Kazuya Kanehisa scored a Japanese VMA with his animated video for Hai Yorokonde, a phenomenon last year.

One more from America: artist Kat Tsai (Across the Spider-Verse) now has a newsletter, where she’s sharing insider tales from the industry. The latest is her experience on Kipo at DreamWorks.

Lastly, we went behind the scenes of Hermína Týrlová’s anti-Nazi film The Revolt of the Toys (1947), a stop-motion classic.

Until next time!

See the article “Animacija — sloboda i budućnost filma,” collected in Zagrebački krug crtanog filma 3 (The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 3).

See The Atlantic (December 1962).

As quoted in Animation Magazine (Winter 1989).

Ronald Holloway wrote this in his book Z Is for Zagreb. He’s also our source for the “complete puzzle” quote later in the article.

Vukotić made these arguments in the 1957 essay “Koncepcije i želje našeg crtanog filma,” collected in The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 3.

This list of Cannes screenings is recorded in The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 1.

Grgić’s quotes about Kristl come from the interview “Redatelj bez poruke,” as seen in The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 4.

For details about Štalter’s background, see the November 1969 issue of 15 dana (Vol. 12, No. 6).

Mimica’s quote comes from this interview.

Štalter’s involvement in Balthazar’s name was revealed in an article published by Nacional.

From the interview “Evolucija animacije,” collected in The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 4.

See “Izaći iz otvorenog kruga,” from The Zagreb Circle of Animated Films 3.

This is part of T. M. F. Steen’s column “The Sound Track” in Films in Review (May 1961).

Best newsletter on Substack I swear

Thank you for this thorough article— it was simply outstanding!