Happy Sunday! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And this is the slate today:

1️⃣ In defense of making a mess.

2️⃣ Animation news around the world.

New here? It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. Get them right in your email inbox, weekly:

Now, we’re off!

1: “Substance over style”

There’s always been perfectionism in animation. See Walt Disney, who passed that attitude down to his staff.

In the book The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney, a story from one employee painted Disney as a hopeless perfectionist who’d take “all the pains in the world to get a picture the way he thought it should be.” Someone with absolute disregard for the money and effort it took to chase the ideal movie.1

Sky-high standards allowed the studio to make classics like Pinocchio. But even Disney’s ambitions were limited by the technology back then. Hand-painted cels are imperfect. Analog photography is imperfect. Reels of film are imperfect. Tests came back slowly and, for hard technical reasons, Disney artists could only use a few layers of art and effects. After a certain point, they had to settle for what they could get.

By contrast, digital tools today are faster and more powerful than any of the old Disney equipment. The limitations aren’t the same. They haven’t been for a long time.

In the 2000s, the great indie animator Michael Sporn (Abel’s Island) spoke about the changes that’d come to animation since his start in the ‘70s. Computers were making everything quicker and tighter — he could easily retime shots and undo mistakes, and avoid stuff like “color pops,” “cel flash” and other errors common to pre-digital work.

“These are all positives,” Sporn told the author of The Animation Bible (2008). But he called them “all negatives” in the same breath, even though he’d switched to a digital pipeline himself. As he explained:

Because you are able to have all of the above, you do. Unlimited cel levels can be easily disorganized. Effects can override a simple piece. All those changes keep going on to the point where they push the end back and back. It takes a lot of discipline to say, “This is not all that I wanted, but I have to stop changing it and accept the limited piece I have in hand.” Compromises existed all those years on film — it’s hard to remember that they should exist in a piece you can so easily change... and change... and change.

Digital tools have done so much good that it’s tempting to brush off Sporn’s words. After all, animation is open to anyone now. Teenagers can download Blender for free and make whole movies by themselves, anywhere in the world. But he still raised a valid question: if animation can be tweaked to perfection, when do you stop?

Animators in the VFX industry know that question all too well. When they build the visuals for big movies (Marvel, DC, Avatar, Star Wars), they’re often pushed to perfect everything.

Phil Tippett is a VFX legend from the days of Robocop and early Lucasfilm. He’s continued working into the digital era — he knows both periods. A decade ago, he wrote this about the expectations placed on VFX artists today:

… there’s this weird sort of competition that happens. It’s a game called “Find What’s Wrong With This Shot.” And there’s always going to be something wrong, because everything’s subjective. And you can micromanage it down to a pixel, and that happens all the time. We’re doing it digitally, so there’s no pressure to save on film costs or whatever, so it’s not unusual to go through 500 revisions of the same shot, moving pixels around and scrutinizing this or that. That’s not how you manage artists. You encourage artists, and then you’ll get — you know — art.

Like Sporn put it, the compromises forced by analog tools are gone — anything can be tweaked, endlessly. It’s easier than ever to be a perfectionist. But there are still costs to ordering 500 pixel-by-pixel revisions, and wasted time is only one of them. As Tippett made clear in his full comment, the job turns robotic. The work loses its spark.

In a way, too much perfectionism with digital tools can produce more imperfect results. There’s something to be said, maybe, for accepting a few bumps — a little of that pre-digital mess. Studio Ghibli seems to think so, at least.

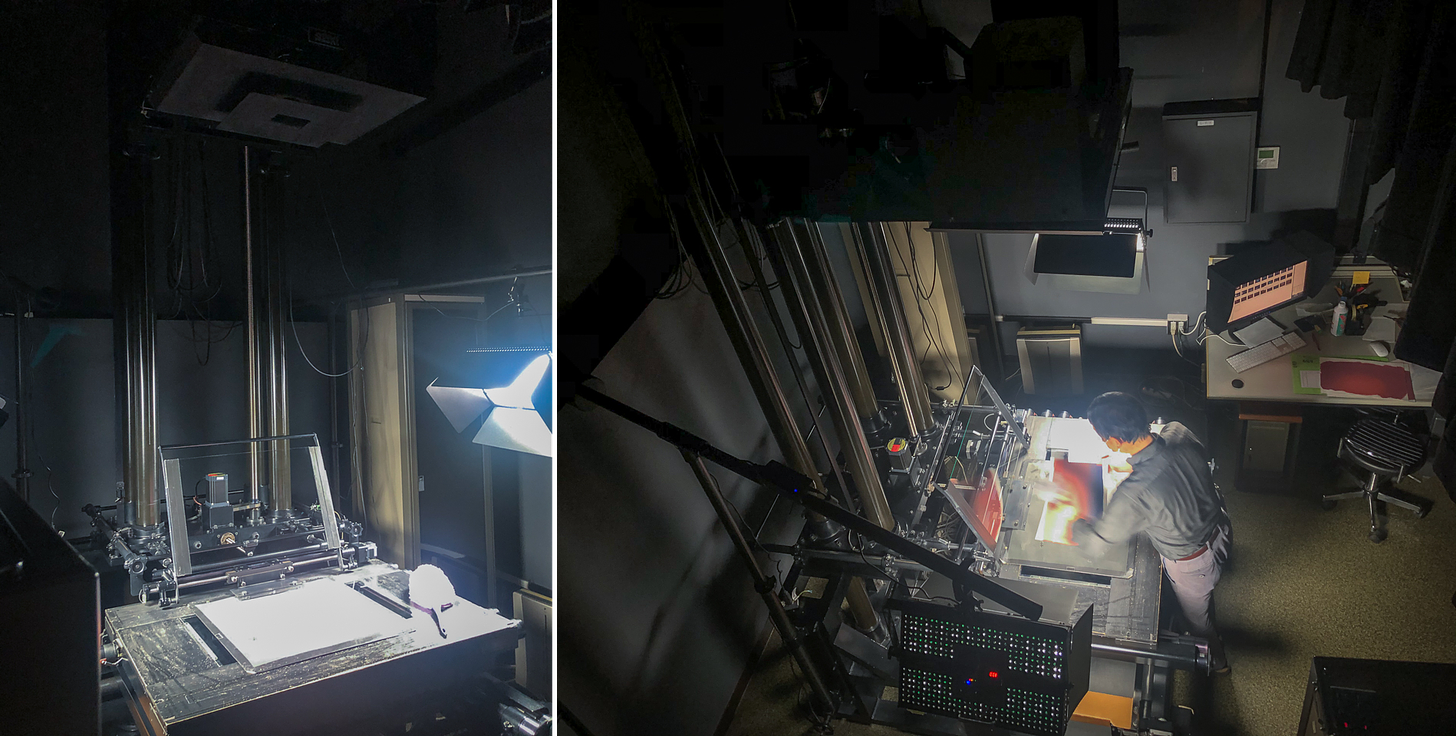

Hayao Miyazaki is a notorious perfectionist — he fine-tunes his films. But Ghibli has tweeted in recent years that its background art process is oddly old school. Background paintings aren’t even scanned: instead, each one is lit with physical light and photographed from above on a digital camera stand. One key reason? To capture the “air” between the camera and the painting, says Ghibli. It’s an imperfect thing, the atmosphere of a physical room in the moment. But it adds.

And it brings to mind the work of another grandmaster perfectionist from pre-digital times: Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog) of Russia.

Norstein and Francheska Yarbusova, his wife and creative partner, make most of their stop-motion films on a multiplane camera stand. Cutouts (and other odds and ends) get piled on the glass — even spread across different sheets. They photograph the unplanned ways that these layers build up, and the air around them. As Norstein said:

The house in Tale of Tales, for example, is made of about ten layers. There’s the house, then more layers of cel with texture on them. And then you draw a few details on the last one. Then the layers play off each other and you get an element of improvisation that’s full of creative energy. […] If you painted the same thing on a flat surface you wouldn’t get the same optical effect. And also, when we get a complex background and then a texture one level above it [on the multiplane animation stand …], then you get a play of the air, of the space. I love that, and Francheska does it perfectly.2

This allowance for quirks and flukes gave films like Hedgehog in the Fog a lot of their charm. It’s one of those feelings you can’t capture without loosening your grip.

Although Norstein himself has attacked computer animation over the years, looseness is really more about an attitude toward tools than it is about tools themselves.

A current animator who shows this is Jonni Phillips from America. She works a lot in the program Adobe Animate, but in a defiantly loose way. Her animation feels free and improvisational: lines wobble, characters distort. Nothing is perfect, but it has tremendous energy.

When we interviewed Phillips about her feature film Barber Westchester (2021), she told us that “going to animation school made me realize that a lot of people get super bogged down with perfectionism, or shooting for some standard that I personally find to be irritating and missing the point of making art. There’s only so much you can do with the limited amount of time we have.”

As she wrote on Twitter:

I prioritize making my ideas actually exist over striving for perfectionism. Like honestly a good way to describe it is “substance over style,” I care more about making stuff exist than I do about making it look pretty.

That philosophy is really close to the one held by an icon of anti-perfectionist animation: Slovakia’s Viktor Kubal (1923–1997).

Kubal was a print cartoonist known for his loose, simple style. He argued that the caricaturist “knows that life is too short for him to be able to say all he wants to say,” and so draws in a fast and direct way. These are pictures that contain only what’s needed to get a point across.

“I would like to draw a caricature with nothing on the paper,” Kubal continued, “and the reader would understand its message anyway. So far, I did not succeed.”

He carried these ideas into his solo-animated features Brigand Jurko (1977) and The Bloody Lady (1980). Even by pre-digital standards, Kubal’s animation is all over the place. He drew quickly and messily. This is work a million miles from Pinocchio: chaotic, haphazard, unrealistic, even awkward. But it still brings energy. It’s still magnetic viewing.

It’s pure “substance over style,” and the imperfections don’t hurt it. In fact, because Kubal embraced them, they add.

Kubal’s drawings didn’t need to be flawless or even good: they needed to read, to communicate, to entertain. For him, that was enough. Like he once said:

I have always considered the content of a drawing to be more important than its form. A precisely drawn bad joke is nothing. But a dashed-off sketch with good content is already something. It is similar with film. A film must first and foremost have content; especially an animated film. If a film has good content, it can be made out of just dots and dashes. And, at the end of the day, if the viewer has had a good time, they won’t even notice that they’ve been entertained by a dot and a dash.3

2: Newsbits

In Italy, Fumettologica published an interview (including an English version) with the Disney great Andreas Deja — about Disney history, his process and more.

Looks behind the scenes of the pan-African series Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire continue. This week, Skwigly in England interviewed the show’s producers.

In Japan, Mantanweb explored the newly unveiled Junk World, the sequel to Junk Head. Director Takahide Hori says it’s even bigger than the first film, which had a team of around three people (this one is around seven). Crowdfunding is ongoing.

Animation Magazine profiled the French film Chicken for Linda, which won the Cristal at Annecy this year and is now coming stateside. “We wanted to make a film that is accessible to children, like the jam jar placed a little too high on the kitchen cabinet: you have to make an effort to reach it,” said its co-director.

Hundreds of employees at Canada’s WildBrain have reportedly signed union support cards, paving the way for unionization with the Canadian Animation Guild.

Meanwhile, in America, VFX workers at Walt Disney Pictures have filed for a union election.

Nigeria’s Trust Radio spoke with graphic novelist Roye Okupe about adapting his Iyanu comics into a series for Max, and more.

In China, the summer box office season has wrapped with a record-breaking haul of 20.6 billion yuan ($2.83 billion). In fifth place for the summer is the animated Chang’an — with more than 1.8 billion yuan ($247 million), per Maoyan.

In Ukraine, the program “Animation Unites” (Анімація об’єднує) gives internally displaced refugee children, aged 9 to 14, a chance to create a claymation film. It was made possible by funding from the EU. See photos.

The Taiwanese feature Luda by director Vick Wang will have its world premiere in October at the Taichung Animation Festival. (Photos and English details here.)

See you again soon!

From The Animated Man (2007) by Michael Barrier. Elsewhere in the book, Barrier showed how the culture of perfectionism affected the Disney studio. He wrote at one point, “As in work on Pinocchio, the appetite for perfection seemed to know no bounds in work on Bambi. ‘There was one scene in Bambi that I shot fourteen tests of,’ the effects animator Cornett Wood said. ‘… That’s the way they worked in the effects department, they really tried. I always had the feeling they tried too hard.’ ”

From the book Yuri Norstein and Tale of Tales (2005), pages 42 to 43.

From page 200 of the book Viktor Kubal: Filmmaker, Artist, Humorist (Viktor Kubal: filmár – výtvarník – humorista, 2010).

This entire article is a *huge* encouragement to me. Having the conviction to make something as an indie artist without worrying about perfectionism is liberating. Thankyou.

It's so interesting how 'style over substance' has been deformed over the years to mechanical perfection, when something organic, simple and beautiful has nothing to do with time spent or polish. Bill Melendez's Peanuts shorts are a fully realised style and wouldn't be 'improved' by cleaning up line work.