Happy Sunday! Hope you’re doing well. This is our plan for today’s issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter:

1) Why Begone Dull Care (1949) is still worth watching.

2) Newsbits.

Let’s go!

1 – Giving the intellect a rest

Animation and music are longtime partners. Everyone knows the hand-in-glove syncing of motion with song in Steamboat Willie (1928) — the way you can see and hear Mickey’s whistling.

Music stars in many classic-era American cartoons. It’s even in the titles: Looney Tunes, Merrie Melodies, Silly Symphony. Disney shorts back then often tied each movement to music in literal ways. Every footfall might line up with the score. They called it “Mickey-Mousing” in the industry.

Still, there isn’t one correct way to express music in animation. You don’t need to be strictly literal. You don’t even need to use characters — for the first part of Fantasia (1940), Disney’s team illustrated Bach with lightly abstract images. Long after, Pixar did something similar with the abstract synesthesia scenes in Ratatouille.

Those parts of Ratatouille were influenced by an animator named Norman McLaren, a Scot who spent most of his life in Canada. He worked from the ‘30s to the ‘80s. Music was a driving force for him, but he expressed it in his own style — at times going fully abstract. His films broke ground and amazed his peers.

A key work of McLaren’s is Begone Dull Care (1949), which brings a wild piece of jazz to life with abstract expressionist animation. It captures the energy of the music in visual form. The film is raucous and thrilling, not to mention gorgeous. People took notice. John Hubley, who directed UPA’s Rooty Toot Toot, recalled:

It was about 1950. [Norman] came out to visit us at UPA, and he brought a new print called Begone Dull Care and showed it to us. It knocked us all over. It was so fantastic. It was direct on film, and it had that marvelous Oscar Peterson track. It was very stimulating to me to see that a film artist can take the path of making his own film and expressing himself. Nobody’s done it better than Norman; he’s been the most pure and the most devoted all his life.1

McLaren wasn’t working for Hollywood or using Hollywood techniques. He’d learned how to make animation with “no story, no script, no conferences, no camera, no shooting and no processing,” as one writer put it. Begone Dull Care was painted and etched directly on film stock. What we’re seeing is a moving art piece.2

That said, McLaren called himself more of an artisan than an artist. He had no pretensions about his work.3 Begone Dull Care, he explained, was only meant “to give the intellect a rest.” Its appeal is a visceral one, right on the surface.

“I want to tell the viewer about my inner feelings; but I don’t want to tell the viewer about my inner thoughts and opinions — you know, intellectualizing,” he said. “In Begone Dull Care, I’m telling them how I feel about that music.”

For him, modern abstracts were like the patterns in folk art, in decoration or in nature. In his words:

... I consider a Jackson Pollock, no matter what its size and price, to be of the same ilk as a piece of marble that has superb graining and coloring and detail. People in the 20th century are not the first people who appreciated Jackson Pollock kind of art. In the villas of Pompeii, during the first period of decoration, the walls were ... painted to imitate marble. Just as Jackson Pollock — he wasn’t imitating anything, but he was creating his own marble.4

Begone Dull Care is McLaren’s marble. For seven minutes, it channels Oscar Peterson’s jazz into shape and color. There’s nothing here to get. The film is entertainment in its simplest form.

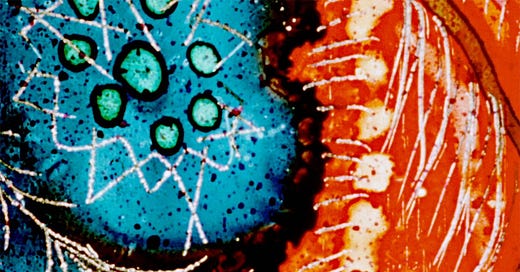

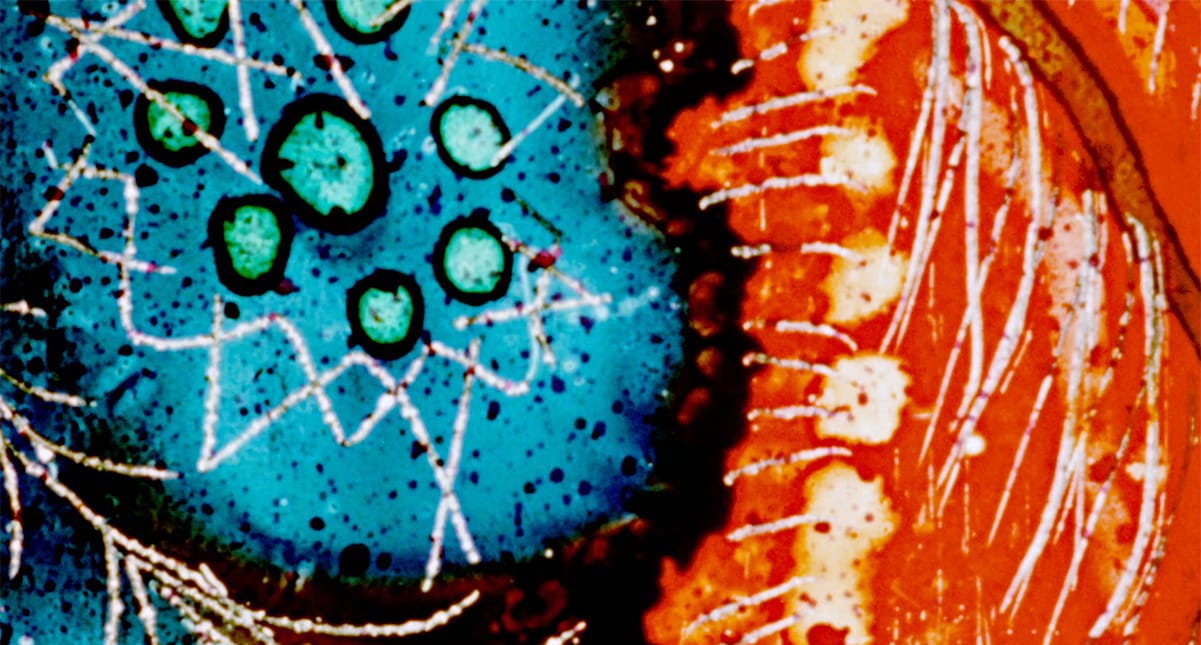

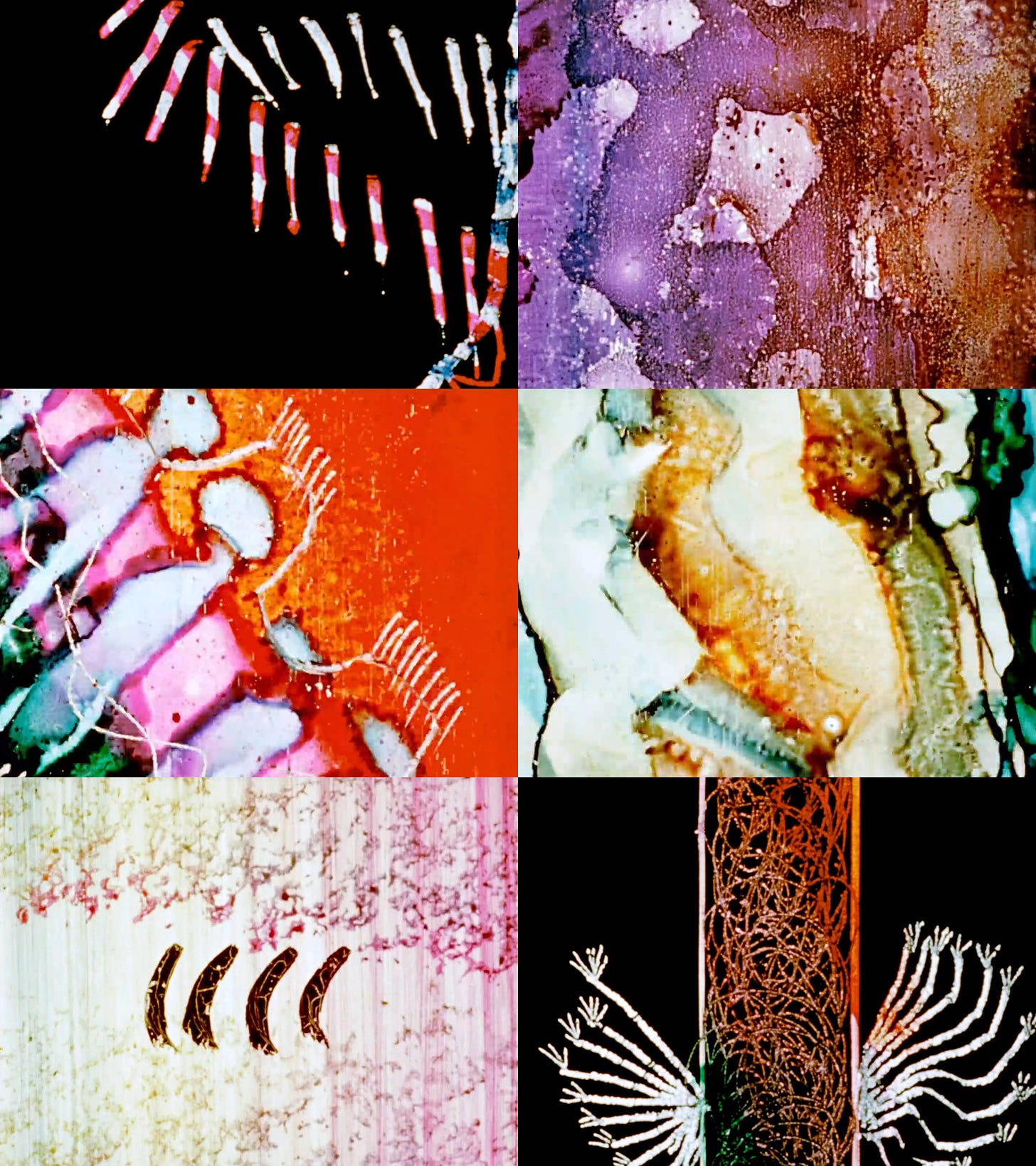

The technical process of Begone Dull Care’s visuals was a strange one. It’s a deeply handcrafted film, impossible to simulate with digital tools.

As he often did, McLaren started with the music. He was a fan of Oscar Peterson and met him in Montreal, at the Esquire Show Bar — a spot played by everyone from Duke Ellington to Charles Mingus. McLaren pitched the idea of animating to Peterson’s music, but it was tricky to explain what that meant.

So, he showed off his films and his workplace — the National Film Board of Canada, whose state funding gave McLaren his creative freedom. A few weeks later, the score was done.

“I guided Oscar by telling him that I wanted silence here, very gentle music there, then something fortissimo or pianissimo,” McLaren said. “He was prolific. For everything I asked, he offered me ten examples.”5

With the music in hand, there was a film to assemble. And McLaren didn’t assemble it alone. His co-creator and co-director on Begone Dull Care was Evelyn Lambart — his collaborator for much of his career. They were natural fits as artists.

First, they measured Peterson’s music, filling out exposure sheets and marking up the film stock. This let them time their artwork to the notes. McLaren gave Begone Dull Care a three-part, “A-B-A” musical structure: fast at first, then slow, then very fast.6 The music did this. The visuals would follow.

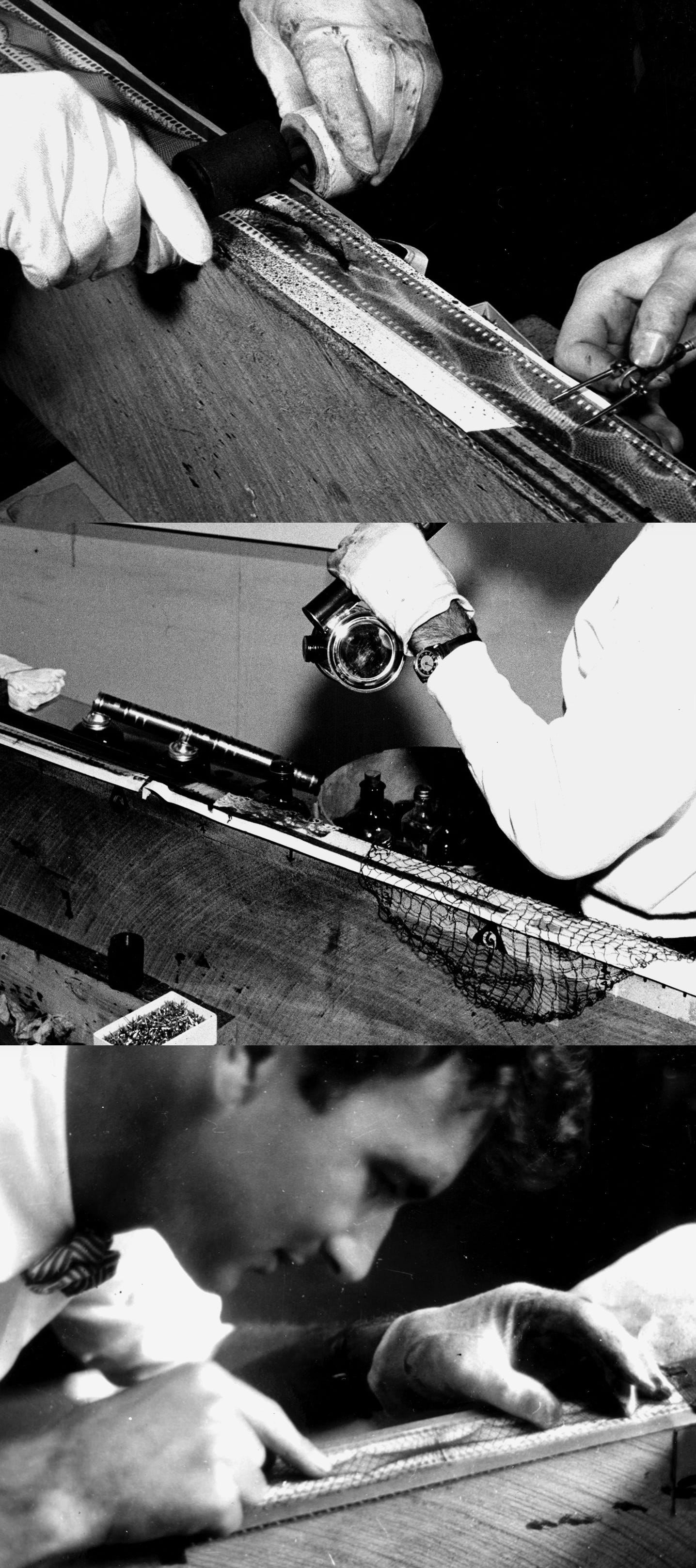

Those were the guardrails for the creative chaos ahead. From here, McLaren and Lambart used every trick they could find to illustrate the film stock. According to American Cinematographer:

For some sequences, a sponge was used to apply a quick-drying paint … to the film as it ran through the [Moviola]. By moving the sponge from side to side, stripes were made to sway across the film. Another sequence involved scratching lines on running black leader with a pin.

A tooth comb, ball bearings, lace, hair nets and gear wheels also were used in applying the paint. An ordinary fly spray gun shot the stuff onto the film through everything from dishcloths to chicken wire to give different textures. Some of the film was sandpapered before the paint was applied to give a smoky result. Doodling with a pointed knife on a layer of paint was tried, and found successful. Both acetate and nitrate film stock were used, and every surface reacted differently to the paints.

Improvisation and experiment were the heart of Begone Dull Care. Lambart called it “a film of accident.”7

For example, some of their paint cracked after drying, which upset McLaren. Then he saw the patterns it was adding: it had only helped their art.8 Another discovery came when “the projector scratched the film annoyingly as it was run through,” Lambart said. It created visual interest, so they started scratching the film on purpose.

There was the dust, too. Their studio building was old and not the cleanest — and their artwork often got dirty. Like McLaren said:

… we were cursing the dust; it settled on our partially painted film and sometimes ruined everything. One day we had just painted very carefully several feet of film when it fell to the floor while still wet. We were furious. But on picking it up, our fury turned to excitement. We discovered a curious phenomenon; the wet dye had pulled away in serrated circular shapes from each grain of grit, making a splendid overall texture. … From that time on, Eve started collecting different kinds of dust which she catalogued in small boxes from fine-powdery to coarse-rough. It was marvelous for making new effects.

Their enemy became their ally. There were times, Lambart remembered, when the two of them stomped their feet to raise as much dust as possible.

Despite the mess, they made a film that holds together. McLaren compared Begone Dull Care to “wild folk dancing” — and, like folk dancing, it has a method. With abstract animation, he knew that “too much monotony, or too much diversity,” risked losing the viewer. His earlier abstract Fiddle-de-dee (1947) was a bit dull, he felt. This new film was his chance to do it right.

Dividing Peterson’s music into “paragraphs and sentences,” he and Lambart painted and etched along to its many changes. That took iteration: McLaren said that they made “five or six versions” of every small section. Since they animated on film stock, they could play back their animation with the soundtrack right away — checking their work without shooting or processing anything.9

And so Begone Dull Care emerged from tests, mistakes and happy accidents, which McLaren and Lambart edited until only the good stuff was left. The result was a classic.

Many who watched it were changed, and not only at the time. In the ‘70s, this film flipped the world upside down for critic Leonard Maltin. “The impact was tremendous,” he said.10 It’s worth remembering: Begone Dull Care comes from the movie theater era. The film is a wall-sized painting in constant motion, shaped by McLaren’s famous sense of timing.11

It offers a lot even in a YouTube window. Begone Dull Care isn’t for everyone (McLaren has always frustrated some people), and it’s not for anyone sensitive to flashing images. But, if you turn up the volume and put it on your biggest screen, the visceral effect from the ‘40s may hit you in 2024. Begone Dull Care still looks and sounds great. And what else is there to say about it?

2 – Newsbits

In England, The Line is developing its viral short The Mighty Grand Piton into a feature film. See Catsuka for details, and YouTube for the original short.

More from England: a new commercial, The Receipt, was made by “printing 900 2D frames onto individual shop receipts and then animating them in stop motion.”

The Chilean directors of The Wolf House are working on their next film, Hansel & Gretel. Via Radix, see the nightmarish behind-the-scenes material they’ve been sharing (this video is a highlight).

In Canada, the Short Films Audio Awards are open for submissions until the end of August. They accept shorts from around the world, reportedly with no submission fee.

From South Africa: an impressive trailer for Isaura, a series in development.

Don’t miss the trailer for Olivia & the Clouds, a feature made with kaleidoscopic collage. Olivia comes from the Dominican Republic, it premieres this month and Miyu Production just became its distributor.

Italy had a retrospective on animator Theodore Ushev (The Physics of Sorrow). In an interview for the occasion, he told the paper il manifesto that his works are “polymorphic exercises in incoherence.”

Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name (2016) was re-released in Chinese theaters, where it’s succeeding again. The film’s total box office has risen to 705 million yuan (around $98.5 million), up from the 576 million it’d earned before.

There’s a teaser out for Dalia and the Red Book, a feature by David Brisbano of Argentina. It’s set to premiere in October after many years in the works (the project started to draw serious attention back in 2017).

Lastly, we wrote about the great Luce and the Rock in honor of its public premiere on YouTube. (You can watch the film here.)

See you again soon!

As quoted in the book Redesigning Animation. Hubley’s words were originally printed in Animation: A Creative Challenge (1973).

The quote in this paragraph comes from American Cinematographer (January 1955), a major source today, quoted throughout.

McLaren’s point about being an artisan comes up in Canadian Art (May/June 1965), in the article “The Unique Genius of Norman McLaren.” We drew from this a few times.

McLaren says this in the documentary Creative Process: Norman McLaren, also used a few times.

The details about Peterson’s involvement come from Séquences (October 1975).

See The Film Work of Norman McLaren and Norman McLaren on the Creative Process, both quoted several times.

This story is told in The Ottawa Journal (September 21, 1974).

McLaren’s comment about iteration is quoted in this article. The point about “paragraphs and sentences” comes from his technical notes for Begone Dull Care.

Maltin told this story in The Vancouver Sun (October 26, 1994).

Love, love, loved this issue. It's kicking off my week right. Thank you yet again.

Another great piece. Your exploration of Begone Dull Care was both informative and captivating. I especially appreciated how you delved into the unique artistic process behind the film and emphasised its impact on animation history. Your ability to connect McLaren's work with broader themes in animation enhances your appreciation for this timeless piece.