The Testing of 'Son of the White Mare'

Plus: 'The Storm' and more animation news.

Happy Sunday! It’s exciting to be here. Our scheduled break is over — and we’re back with the first Animation Obsessive issue of 2024.

We got to relax in the past few weeks, but lots of prep and research happened, too. Books arrived from places like Japan and Czechia, and we ordered one from Croatia that we’ve been tracking down for more than a year.

There was time to study Night on the Galactic Railroad and the early works of Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki, and time to organize our research material to make it easier to use than ever. The extra time even benefited today’s issue — about a film we’ve wanted to cover for a while.

Which brings us to our slate for today:

1️⃣ The story of Son of the White Mare (1981), a Hungarian masterpiece.

2️⃣ The Storm, plus other animation news from around the world.

In 2024, we’re planning our most ambitious set of stories yet. If you’re just finding us now, it’s a great time to sign up:

With that, let’s begin!

1 – A nightmare and a dream

Son of the White Mare is one of the big ones. It’s never been famous — in fact, it was deeply obscure until the 2000s, when it started to spread online.1 But it’s secured its place in the canon. It stands with the greats.

The film comes from communist-era Hungary, back in 1981. And the viewing experience is hard to put into words: it’s all searing colors and morphing figures. Son of the White Mare flips an old folk tale into a psychedelic odyssey that keeps going (and going) for more than 80 minutes.

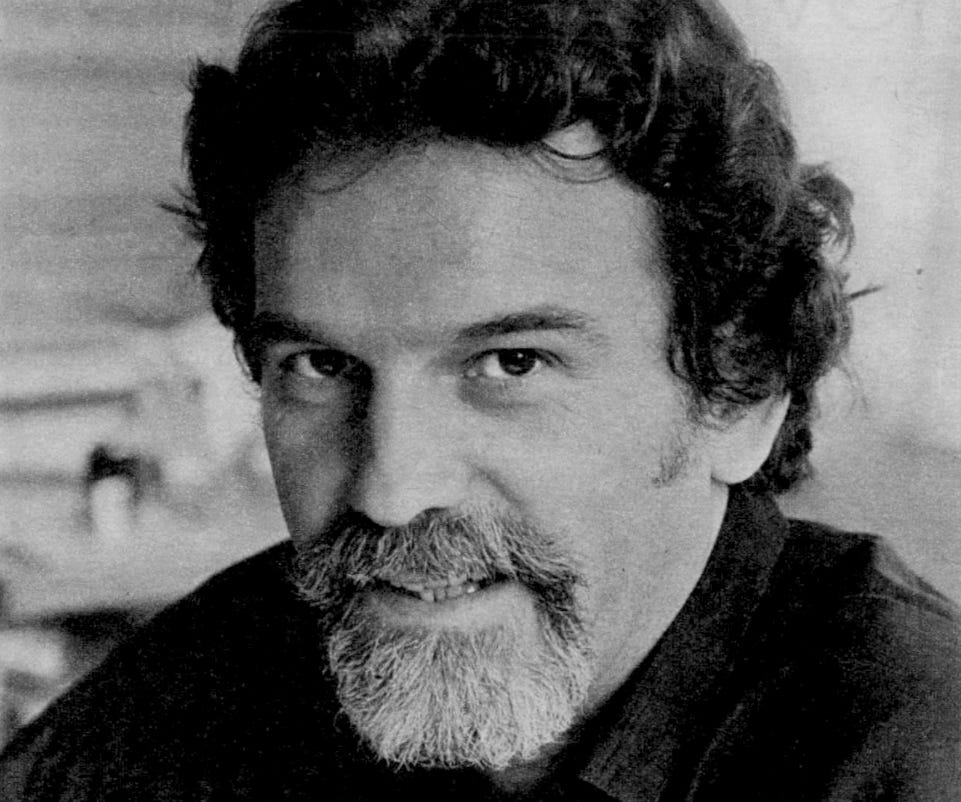

Yet its director, the late Marcell Jankovics, tended to resist the descriptor “psychedelic.” As he said, this film isn’t really tied to psychedelia at all:

Dreams inspired the pattern for Son of the White Mare. What was referred to as “psychedelic” by the press actually came from the fact that — I’ve never tried psychedelic drugs, but their effects are close to dreaming.2

That was only part of it. Jankovics tended to be analytical, even scientific, in his work. He filled Son of the White Mare with the symbols and patterns he’d found while studying folklore and myth. The film’s intense color gradients, he said, came from Goethe’s Theory of Colors: “morning is green, yellow is noon, twilight is red, night is blue, with transitions.” And everything here rests on the idea of cycles — and circles.

Still, the result isn’t a mental exercise. What Jankovics made overwhelms the senses. Son of the White Mare feels more like a vision than it does a film. And it’s a vision only he could’ve directed — although he himself almost didn’t succeed.

The basic thrust of Son of the White Mare is that Treeshaker, the human son of a horse, has to save three princesses and defeat three evil dragons. He’s joined in his quest by his two brothers. This pattern of three rules the film, down to the setup of many shots — you feel the logic of ancient legends coursing through it all.

It’s a simple, elemental story adapted from the Hungarian folk tale Fehérlófia. But it’s stretched into a feature-length film in which (as Jankovics said) “the design of every frame is of great importance, as if it would be a painting.”3

Animated features were new to Hungary in the mid-1970s, when the seeds of Son of the White Mare were planted. The country’s first one, the visually explosive Johnny Corncob, only arrived in ‘73. Jankovics had directed that, too.

Johnny Corncob was grueling to make (Jankovics’s short Sisyphus is a memoir of the time) but a huge hit. It quickly drew over a million people in Hungary, then screened for years. So, Jankovics began to think about his next movie. He told the press in 1975, “I want to make a film called Égig érő fa (‘Sky-High Tree’) based on the ancient Hungarian and Finno-Ugric world of belief-myth, and I am now writing the script for it.”4

That’s when the problems started. Sky-High Tree was soon rejected by Pannonia Film Studio, where Jankovics had overseen Johnny Corncob. It was Hungary’s main animation workshop, based in Budapest and state-funded. As he said in 1981:

When I finally devised the film’s structure and wrote the screenplay … the studio management didn’t receive it well. ... A game of wrangling followed, changes were made, and by 1978, when I completed the book on which Son of the White Mare was based, I found myself deviating from my original vision.5

Jankovics couldn’t admit it publicly back then, but politics had led to the rejection. He’d written his own story, inspired by folklore, that described time as an eternally recurring cycle. Communist doctrine held that time was a straight line of progress. To deny that was to deny the system. So, Jankovics’s film was out.

But theories like these kept consuming him — he was going deep into the old stories. That 1978 book he wrote was a “structural analysis of Hungarian folk tales,” which took three years of research and won a state award. Jankovics, who’d never gone to college, became a leading and lecturing expert on folk tales. It fed into his animated TV series Hungarian Folk Tales, in part a testbed for Son of the White Mare.6

You could call White Mare a compromise after the failure of Sky-High Tree. It’s a retelling of a folk tale that, at a glance, has no ideological bone to pick. But he hid the same ideas below the surface, inside the visuals. As Jankovics told Cartoon Brew in 2015:

The circular movements in [Son of the White Mare] refer to the eternal return of time and space, the seasons and the days. That’s also the reason I used a circular spectrum of colors where violet and red meet in purple. The three heroes of this fairytale, as in most Hungarian mythic tales, are suns. In this case there’s the morning/spring sun, the culminating/summer sun, the setting/fall sun. At least this is my theory on the fairytale.

Overall, the pitching and pre-production of Son of the White Mare were rough on Jankovics. He said that he storyboarded the whole film twice, each pass taking around 1,200 drawings — in the ballpark of 2,400 total. He planned the visual transformations, the morphing of one image into the next, in written notes beside his storyboard sketches.

“The ‘experience of transition’ comes to be via screening,” Jankovics said, arguing that still drawings couldn’t portray it. “It is the extension of Eisenstein’s montage theory to animation.”7

Finally, after years of fighting, he got Son of the White Mare greenlit at Pannonia.

By the late ‘70s, Jankovics was talking to the press about Son of the White Mare in the form we recognize it today. He told a journalist that he’d even included the eight roles he identified in folk tales: “the hero, the helper, the bestower, the one who sends the hero on his way, the girl sought, the foe, the pseudo-hero and the magic tool.” A vast theoretical framework was in place. But production took years from there.

In those days, creativity fueled Pannonia. The studio had artists like Kati Macskássy and Sándor Reisenbüchler (The Kidnapping of the Sun and Moon), who did some of the world’s most boundary-shattering animation. As Jankovics said, they pushed each other.

It took Pannonia’s pool of talent to create Son of the White Mare. Key to its design and color was Zsolt Richly (The Rabbit with Checkered Ears), who worked with Jankovics on the look. For the film’s characters, Jankovics said that “a back-and-forth game flowed between us: we molded and redrew each other’s designs.” Richly had pioneered the use of Hungarian folk art in animation, and his influence is felt here.8

Then there was the dialogue, recorded before animation began. Jankovics cited the intentional “dreaminess of the voice acting,” meant to capture the “way we remember how our mom, or grandma, or dad, or grandpa would tell us a tale” before bed. It ties into his theories about folk tales once again, as does the surreal score.

He claimed to have animated a third of Son of the White Mare by himself, collaborating with key animator Edit Szalay and others. Szalay “worked a great deal and very well on the film,” Jankovics said (she’d been his partner on Sisyphus). Taking charge of the backgrounds this time was László Hegedűs, described by Jankovics as a major talent who was “very hard to work with.”

In fact, team problems were rampant. Pannonia’s collegial vibe broke down: artists were out to assert themselves on Son of the White Mare and there was no “real team spirit,” according to Jankovics. Things got harder when the film’s colorists went into open revolt, demanding higher wages from the studio in return for the difficult work.

Adding to it all, Pannonia wasn’t built for a film this ambitious. As Jankovics said in 1981, Son of the White Mare took “600 colors, 130,000 frames and 65,000 drawings,” and there was consistent trouble with the supplies:

... the studio’s equipment is extremely outdated. We have to paint on poor-quality material. Usually we work crammed inside wood cabins that are poorly technically equipped. Our company has to search for foreign currency with which we can buy new editing tables. Therefore we deal with contract jobs, which suck away enormous creative energy … Some of the purchased cels are scratched or wrongly pressed, and the paint peels off. The quality of the paint is also immaculate: it clumps. All of this causes extra work. It was more than once that I saw my colleagues sobbing. For example, it turned out that the deficiencies just now mentioned caused one of them to waste six hundred pieces of painted celluloid.

By this point, even before the premiere, Jankovics was demoralized and admitting it in interviews. The film’s production had been longer and tougher than Johnny Corncob’s, not counting the years he’d battled to get Sky-High Tree and White Mare approved. “I feel the pains of childbirth,” he said, “after an overdue pregnancy.”

When the film opened in October 1981, it drew around 400,000 theatergoers — a steep dropoff from Johnny Corncob. It was even worse compared to Vuk (1981), an animated feature released just after Son of the White Mare to an attendance above two million.9 Jankovics’s film was seen as a letdown, and Hungarian reviewers, while interested by it, weren’t head over heels.

Jankovics later summarized:

I had to suffer terribly for the film. The struggle for its realization consumed most of my energy. ... Afterward, both its distribution and reception were disappointing. My parent company, Pannonia, put me in cold storage.

White Mare began to feel like a painful misstep to Jankovics. He still enjoyed Sisyphus and even the rushed Johnny Corncob, but not so much this one. “I don’t like watching Son of the White Mare,” he said in 1988. It wasn’t just the poor reception, either. He saw the film as deeply flawed and even a little boring.

Sidelined at Pannonia, he spent much of the ‘80s doing academic work on folklore, dividing it with his time on Hungarian Folk Tales. His other film and TV ideas kept falling through.

Meanwhile, despite little distribution, Son of the White Mare was growing a tiny cult abroad.

The American critic Charles Solomon saw the film in the early ‘80s. Writing about its Academy screening in 1983, he called it “the most visually innovative animated feature since Yellow Submarine … completed for the astonishingly low figure of $400,000 — less than a half-hour, prime-time special here.”10

Solomon turned into a champion of Son of the White Mare. A few years later, he placed it among the best animated films of the ‘80s and said that it “raised the animated feature to heights that transcend even the vision of Walt Disney.” In the ‘90s, he played a White Mare bootleg for Disney’s Roger Allers, who subsequently hired Jankovics to work on Kingdom of the Sun before it became The Emperor’s New Groove.

In the decades after its debut, Son of the White Mare was overshadowed in Hungary by Jankovics’s other projects, more or less becoming a footnote. Yet all of the little connections added up — Solomon and Allers, and Peter Chung (Aeon Flux), who became a follower. Stuff like this primed the film for a comeback, especially abroad.

In the 2010s, White Mare was restored in 4K under Jankovics’s supervision. The film’s first major release in America, a gorgeous Blu-ray edition by Arbelos, was reviewed well and widely. The New York Times called it a “should-be classic.” Even in Hungary, its reputation has bounced back in recent years as a masterwork “ahead of its time.”

During the restoration and re-release process, Jankovics finally watched Son of the White Mare again. It’d been decades. The sting of the old days wasn’t as intense. He’d warmed a little to his grand, strange vision of a film. As he said in 2020:

I see its mistakes, its virtues, the fact that it has stood the test of time and that a new generation of viewers derive joy from it makes me happy.

2 – Worldwide animation news

The Storm arrives

We’ve been waiting for this one. In China, The Storm premiered on January 12. It comes from director Busifan, whose last film was the cult success Dahufa (2017) almost six years ago.

To accompany this release, Busifan has hit the press circuit. The Storm stands out as a 2D feature — something akin to an endangered species in China, as The Paper noted this month. And it has the signature weirdness that’s powered most of his work. Busifan said in a new interview that it’s not exactly weird-on-purpose: he just hates cliches and familiarity, and tries to undermine them whenever they appear in his art.

The Storm is about a father and his adopted son, who board a “black ship” with an array of other creatures and spirits. It’s a personal project for Busifan, an expression of his own view of the world.

The story, he said, was inspired by the environmental devastation of his rural hometown. He wanted to grapple with the forces of greed and selfishness that drove it, and with the fallout they’ve caused. The film’s Chinese title is 大雨 (“Great Rain”), tied to Busifan’s idea of a grand, purifying rainfall. He cites a novel, Lao She’s Rickshaw Boy, as a key to understanding it. One translation reads:

The rain falls on the rich and the poor alike, it falls on the righteous and the unrighteous alike. But actually, the rain is not just at all, because it falls onto a world where there is no justice.

The Storm is a more ambitious film than Dahufa. Busifan’s projects until now have been tiny — he admits that it was a struggle even to know what to do with a real budget. His process needed to transform.

But he avoided over-polishing. Many on his team are young and reportedly from rural China, and Busifan admits that their “technical ability is not that strong.” He likes it that way: it adds what he calls a “clumsy sincerity.” He tried to tap a sense of flawedness throughout The Storm, as “too much polish ... can bring an industrial feel.”

Busifan’s last film wasn’t a runaway hit, particularly at first, and that’s true of his new one as well. The Storm has pulled in a modest 9 million yuan (around $1.26 million), including an opening day of 2.5 million yuan, which landed it in eighth place at the box office. Dahufa slowly climbed above $13 million after a weak start.

It’s too soon to tell whether Chinese fans will accept The Storm as a second cult classic. On Douban, there’s widespread praise for its visuals, although some fiery blowback against its script (a complaint leveled also against Dahufa). The site hasn’t given it an overall star rating yet, as of this writing.

Whatever the case, we’re hopeful that The Storm will be distributed outside China. Dahufa never got a wide release in English, and Busifan’s other work (barring Valley of White Birds) remains almost unknown internationally. We’ll be watching for more. Until then, you can see a trailer for The Storm below:

Newsbits

The Boy and the Heron has now earned around $42 million in America, making it the fourth-biggest anime film ever in the country. It’s within swinging distance of third place: Pokémon the Movie 2000 ($43.7 million).

The main story of January is from America, and you’ve heard about it: Mickey Mouse is in the public domain. But did you know that a film restorer has now scanned Steamboat Willie in 4K? The uncompressed version is over 34 GB.

Speaking of restoration: it turns out that the Japanese series Sailor Moon wasn’t meant to have a pink tint, and its original TV airing didn’t. Film decay added it to later releases.

Animator and podcaster Giulia Martinelli has a new interview with Britt Raes of Belgium, covering her great Luce and the Rock. Also check out her chat with Tal Kantor, whose Oscar-shortlisted film Letter to a Pig is on YouTube for now.

The British writer Alex Dudok de Wit (translator of Shuna’s Journey, author of the BFI’s Grave of the Fireflies book) has started an animation newsletter.

In Hungary, animator Réka Bucsi has received a state grant of 5 million forints (around $14,400) to develop her first feature film.

Estonia’s Priit Tender spoke to Cartoon Brew about his favorite shot in Dog Apartment, his remarkable Oscar shortlistee. Elsewhere, Tender says that a nomination “would be great for my country … it’ll be a strong argument for our film funds to continue supporting independent animation.”

An intriguing story from South Africa: a lawyer quit her job and founded an animation studio, which then contributed to Disney’s Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire.

In China, scholar Fu Guangchao has an immense new piece out on the tale of “China’s Yasuo Otsuka”: animator Du Chunfu.

Lastly, the Russian animation scholar Pavel Shvedov rounded up more than 50 festival films from recent years that are now online for free. A number of them, like Naked and My Galactic Twin Galaction, are very good.

See you again soon!

In 2008, Cartoon Brew’s Amid Amidi watched Son of the White Mare for the first time via a YouTube upload. His post about it attracted a reply from Peter Chung, who’d encountered the film in 1984 and been searching for it since. The internet reunited him with it. As Chung wrote elsewhere, “This generation of animation fans have no idea how blessed we are these days.”

From Brighter Colors: Marcell Jankovics in Conversation, a long interview included on the Arbelos release of Son of the White Mare. We cite it a few times.

From Cartoon Brew’s 2015 interview with Jankovics, quoted multiple times.

Jankovics said this in Film Színház Muzsika (August 8, 1975). The details about Johnny Corncob’s success also come from an article in Film Színház Muzsika (October 1, 1988), cited throughout.

From an interview in Film Színház Muzsika (May 2, 1981), an essential source today. Jankovics talked about the rejection of Sky-High Tree in this interview as well.

See Film Színház Muzsika (March 17, 1979). The detail about three years of research comes from Közhírré Tétetik (October 1980), one of our most-used sources today. (As a side note, Jankovics had tried to go to college years earlier but been rejected — he and his family were persecuted for political reasons.)

Jankovics said this in Filmkultúra (1984, issue 5), and once called metamorphosis his signature in the same magazine (1978, issue 3). Other details about the storyboarding of White Mare come from Film Színház Muzsika Kultúra (September 1996) and the previously cited Film Színház Muzsika (May 2, 1981).

Richly’s status as the creator of Hungarian folk art animation is underappreciated, but that’s the case made by Ferenc Mikulás, a giant in Hungarian cartoons.

Data from Eszter Diszeri’s book Frame by Frame (Kockáról kockára, 1999). It’s a history of Hungarian animation that, maybe unsurprisingly, doesn’t have a lot to say about White Mare.

From the Los Angeles Times (March 30, 1983). The line about Disney also comes from the Times (June 11, 1985).

I love Jankovics' view of metamorphosis as a signature trademark of animation akin to the cut in cinema, as well as his approach to design, very few directors have such an informed idea of what the medium can uniquely accomplish. And what they were able to pull off back then under such limitations... Eastern Bloc-era animation is something else. Very glad that he came to terms with Fehérlófia before he passed away; it's one for the ages. His deep interest in folklore and History also resonates with me very strongly, there's even a documentary about the story of his family: https://vimeo.com/658703693

Great that you plan to cover "Night on the Galactic Railroad", another rather neglected classic that I saw in the cinema in Tokyo in 1985 - I still have the brochure of the film that could be purchased in the cinema foyer.