Welcome! As 2022 draws to a close, we bring you one last issue of Animation Obsessive before the New Year. We’re going out with a bang. Here’s the plan:

1️⃣ Creating the backgrounds for Tokyo Godfathers.

2️⃣ International animation news.

3️⃣ [UNLOCKED] Our 2022 signoff, and our hopes for 2023.

If you haven’t yet, you can sign up for our Sunday issues — you’ll be the first to know when our next one drops:

Let’s get going!

1. “More realistic!”

Tokyo Godfathers (2003) is an unlikely holiday film. Its director, Satoshi Kon, wasn’t trying to create a rival to Rudolph — this is far from a Christmas special or a family movie. But it is a fun, heartwarming, emotional and endlessly rewatchable story that revolves around Christmas. So, here we are again.

Last year, we wrote about the magical characters who power Tokyo Godfathers. For Kon, this film was an experiment in acting — extreme, cartoony gestures and facial expressions take center stage. His animators, many of them Ghibli veterans, ensured that the lead characters Hana, Miyuki and Gin delivered memorable performances in every stage of their quest to return a lost newborn home.

But it took one other component to make their acting really pop. Kon’s team contrasted the cartooniness with one of the most detailed worlds ever to appear in a 2D animated feature. Under art director Nobutaka Ike, the backgrounds became close to photoreal. As animator Aya Suzuki recalled from her conversations with Kon:

All the animators started going really wacky and mad and very expressive. And he said, every time the animators were getting crazier and crazier, he had to instruct Ike-san, the art director, “More realistic! More realistic!” Because the animation was becoming so surreal, he needed something to keep the world in reality.1

On his blog, Kon made it clear that this contrast was the point of Tokyo Godfathers. “The basic concept of this work is the ‘coexistence of conflicting images,’ such as ‘realistic and unrealistic’ or ‘tragedy and comedy,’ ” he explained.

The film needs backgrounds as real as the animation is unreal. Only then do viewers feel the intended effect.

Which is why the world of Tokyo Godfathers looks so lived-in and elaborate. It’s based on the everyday Tokyo of that time — not the parts of the city seen in media. Many stories idealize Tokyo or hyperfixate on its grim underside, Kon wrote. He wanted to show the messy, contradictory city that existed in real life. Ancient torii gates near new apartments. Homeless camps near government skyscrapers.

Here’s what Ike said:

I was interested in exploring parts of Tokyo not usually seen, like the alleyways and paths I would take on my way to work. I’d always wanted to show Tokyo as I knew it. The director shared my desire. When he told me he’d be using that side of Tokyo in his next film, I knew the job was for me. We tried to be extremely faithful. We wanted Tokyo to become a character in itself.

Digital photography was the tool that made it possible. Kon and his team scouted the city and took pictures of everything — a process that continued well after the pre-production phase. “We even took pictures on the way to work,” Ike said.

Real details and locations made their way into Tokyo Godfathers, but it wasn’t a matter of tracing photos. Most of the areas in the film, Kon wrote, were invented — just “likely places” based on their heaps of reference. Kon and his artists looked at their pictures, borrowed what they wanted and jammed disparate ideas together. They were building “places that feel like they could be in Tokyo.”

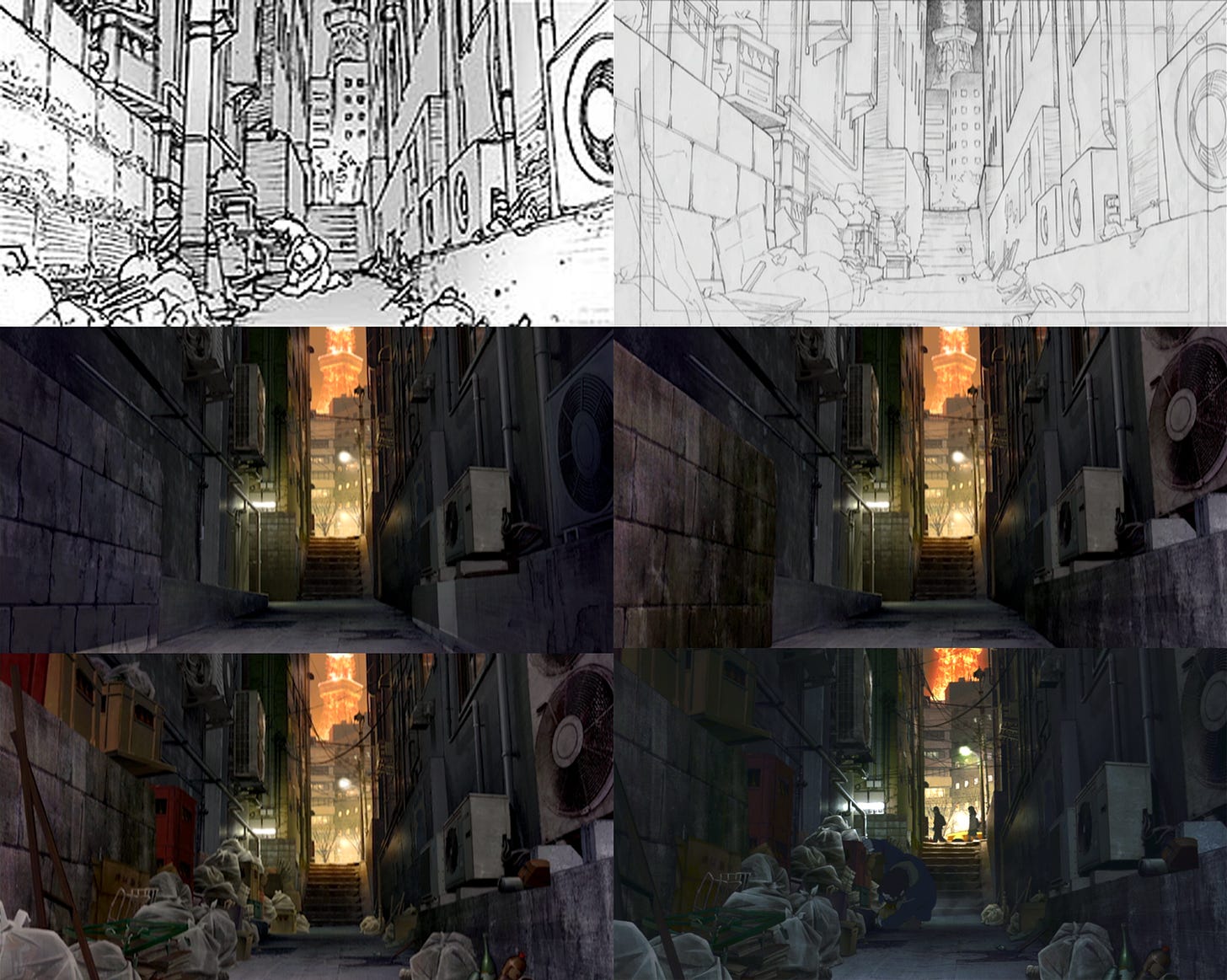

In fact, Kon saw it as fatal to copy the photographs too closely, even for locations based on real ones. The artists risked falling “into a labyrinth of details without grasping the essential composition and structure of the object.” The photorealism in Tokyo Godfathers was always added after a clear, simple, solid blueprint was in place.

Kon didn’t tell his artists to simplify the world in the Kazuo Oga style, though, where key elements are rendered in detail and others are omitted. “The most important thing was to draw out all the little things you may find on the streets of Tokyo. Never to ignore them,” Ike said. “The director asked us to draw every bit of detail.”

Everything was shown, and then some. “We added 1.5 times more things than in the actual photos,” noted Ike. It’s an elevated hyperrealism — based on tight compositions, but ultimately busier and more detailed than photographs can convey.

In part to help with the backgrounds and layouts, Kon dramatically upped the detail of his storyboards during Tokyo Godfathers. He wrote that it streamlined production — folding the “art setting” (environment model sheets) and much of the layout process into the storyboard stage. If he drew with enough detail, the team could get what it needed just from the boards. Given limited money and staff, it helped.

Kon’s drawings were blown up and made the basis for all the layouts. Roughly 10% of the film’s shots were built on unaltered storyboards, with no extra layout work from the team.

He purposely didn’t get fancy with the camera. “I’ve always disliked showy or ostentatious compositions, but this time the camera positions and compositions are more ordinary than ever before,” he wrote. He left space for the characters to act, and he reused angles and backgrounds as much as he could.

This served a second purpose. Limited camerawork would reduce the number of backgrounds, and in turn “increase the amount of time spent on each piece and thus increase the density of the work,” Kon wrote. Fewer backgrounds equaled more detail. Each camera angle became a puzzle, as Kon searched for a way to get the most out of every single shot.

And the background team certainly used this extra time — finding new solutions to the complex problem of drawing modern Tokyo.

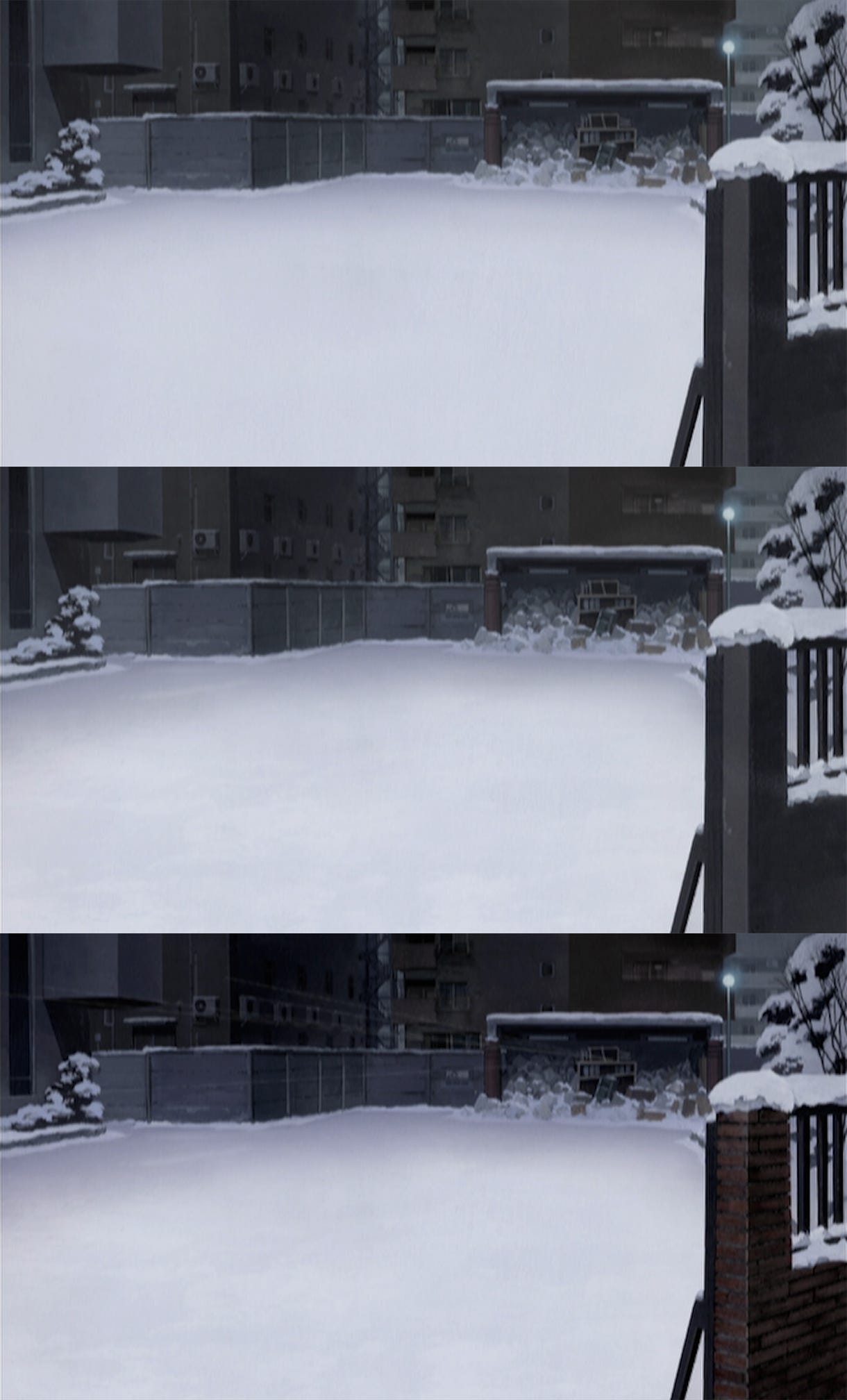

One part was the snow. Typical ways of rendering it weren’t realistic enough. Ike said:

We needed to show some kind of depth in the snow’s surface. So we used a technique we had never used before […] we wanted it to look like real layers of snow, so we painted the snow in white over and over again. As you know the real snow has different layers, especially in piled snow. We wanted to draw piled-up snow realistically. In order to express that, we painted white over white. We made most of the random uneven colors during the painting process to express the snow surface somehow.

And then there was the garbage — bags and bags of it, everywhere. Here’s Kon:

“Garbage” is an important subject in Tokyo Godfathers, and it must be depicted beautifully. It seems that “beautiful garbage” is a bit of a contradiction, but the garbage must make an impression.

The garbage bags were built up in many layers, too, made easier by the team’s recent switch to digital tools. Kon wrote that, earlier in his career, you could only stack six physical cels — ABCDEF. On the computer, you could easily go up to Z.

Most of the look of the garbage came about through “harmony processing,” a Japanese industry term. It refers to a way of mixing background paintings with cel overlays to create a unified image — something that has the lines of a moving object, but the texture of a background object. You know it when you see it. They used it for the bags, but also for an unusually large amount of other background stuff in Tokyo Godfathers.

Again, it came from the switch to digital. The team was able to add many more effects, more texture and detail, than standard cel animation allowed.

When you overlay ink lines on a background object, Kon wrote, it makes that object feel “closer” to the characters. It plays on our subconscious understanding of the laws of cel animation: if something has lines like a character, it’s an active presence in the story. It could move. Combined with the painted texture, it creates a vibe that Kon summed up as “it doesn’t move, but it feels like it might move.” That’s harmony.

By applying this trick to countless objects scattered throughout Tokyo Godfathers, the world was made to feel that much more present.

In a story defined by contradiction and contrast, the only way to balance out Shinji Otsuka’s animation was to set it in a world more real than reality.

A maddening level of care went into the world of Tokyo Godfathers — even more than we’ve covered here. But the effect is undeniable. Satoshi Kon at his most realistic collided with Satoshi Kon at his cartooniest. The two poles united into something magnetic.

2. Newsbits

Our friend and fellow animation Substack writer, Coleen Baik of

, is going through an unimaginable family crisis. She’s started a GoFundMe with the details. Coleen is great — we’ve donated, and we hope you’ll consider doing so as well.In Ukraine, one of the studios behind Loving Vincent is finishing its next painted film. It’s in Kyiv, and it needs a generator for stable power this winter amid Russia’s attacks on the grid. The Kickstarter campaign is almost over, and it’s not quite there yet.

On a lighter note: Hayao Miyazaki’s upcoming film How Do You Live? has a teaser poster and a Japanese release date: July 14, 2023.

In America, animator Momo Wang spoke with Animation Magazine about her Oscar-qualified film Penglai, whose trailer blew us away this month.

Veteran Japanese animator Norio Hikone, one of the lead artists behind the Toei dance sequence we covered last month, posted photos of the storyboard for Doggie March (1963). It’s fascinating stuff, all new to us.

In China, Bilibili and the venerable Shanghai Animation Film Studio dropped a trailer for Yao: Chinese Folktales, an anthology due to start rolling out January 1.

American animator Jonni Phillips premiered the polished, updated, theatrical cut for Barber Westchester on YouTube. Definitely one to watch, whether you’ve seen it before or not.

The French film Little Nicholas: Happy as Can Be finally released in America this week. Animation Magazine has an interview with one of its directors.

Cartoon Movie is coming up in March, and a number of exciting projects have been revealed — among them The Bird Kingdom (Brazil), Chicken for Linda (France) and Cartoon Saloon’s Julián (Ireland).

Also in China, the animated Three-Body Problem series remains a massive hit for Bilibili, but online arguments about its actual quality are raging.

Japan’s Studio Ponoc (Mary and the Witch’s Flower) has delayed its upcoming film The Imaginary to winter 2023.

As you know, there’s a trailer for the American film Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Skwigly has it, plus an interview.

In Paraguay, the series No están solos (roughly, Not Alone) has a trailer. It tackles subjects like deforestation in Paraguay, and the plight of the country’s indigenous peoples.

Maybe the most fun American headline this week came from Variety — Guillermo del Toro Agrees With Miyazaki: Animation Created by AI and Machines Is an “Insult to Life Itself.”

Lastly, our deep dive into Richard Williams’ Oscar-winning Christmas Carol unearthed details about his career we’ve never encountered in our research before.

3. Our 2022 signoff

That’s a wrap.

The Animation Obsessive newsletter hasn’t gone on break since December 2021. For us, 2022 has been full. There’s no succinct way to sum it up. All we can say, to all of you, is this:

Thank you.

We weren’t ready for just how big, and how difficult, 2022 would be. This year has been a trial by fire. We had to grow as we went. Yet readers like you, who opened and enjoyed the newsletter week after week, have powered us forward. We’re not standing in the same place we were in January.

Whether you’ve been a reader since last year, or you’re just joining us now: thank you. It means a lot.

As 2022 winds down, we’ll be using our Christmas and New Year’s break to recharge. This doubles as a chance to prepare for next year. Our twice-weekly schedule forces us to work fast and lean, and certain research takes more time than we’ve had. A long list of ideas is waiting for us. We can finally explore them — and shorten that list starting January. If you’ve liked our work this year, you’ll love what we’re planning for 2023.

Our next full issues will drop January 12 (Thursday) and 15 (Sunday). Folks on our mailing list will hear a little from us before that. Stay tuned. And again:

Thank you!

From the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist (2021), also our source for some of Ike’s words. Our main references throughout were Kon’s ultra-detailed writings about Tokyo Godfathers on his blog, and the Blu-ray special feature Unexpected Tours.

Thank you for sharing so much insights into the animation world. I'm so glad I found your newsletter! I love Tokyo Godfathers, but I saw it many years ago, it's due time I give it a re-watch. Thanks for the reminder!

Harmony Processing. Beautiful.