Totoro Before Totoro

Plus: news.

Welcome! Glad you could join us for another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter — our first of 2025.

Before we begin, we’ve got to bring up the fires in Los Angeles. Many people in the city’s animation scene are struggling. Cartoon Brew has a list of fundraisers for those affected, and Alex Hirsch (creator of Gravity Falls) is running a charity auction through the 21st, which includes original art from folks like James Baxter. Don’t hesitate to share and donate if you can.

With that, our slate today:

1) The making of Panda! Go, Panda!

2) Newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – A point of origin

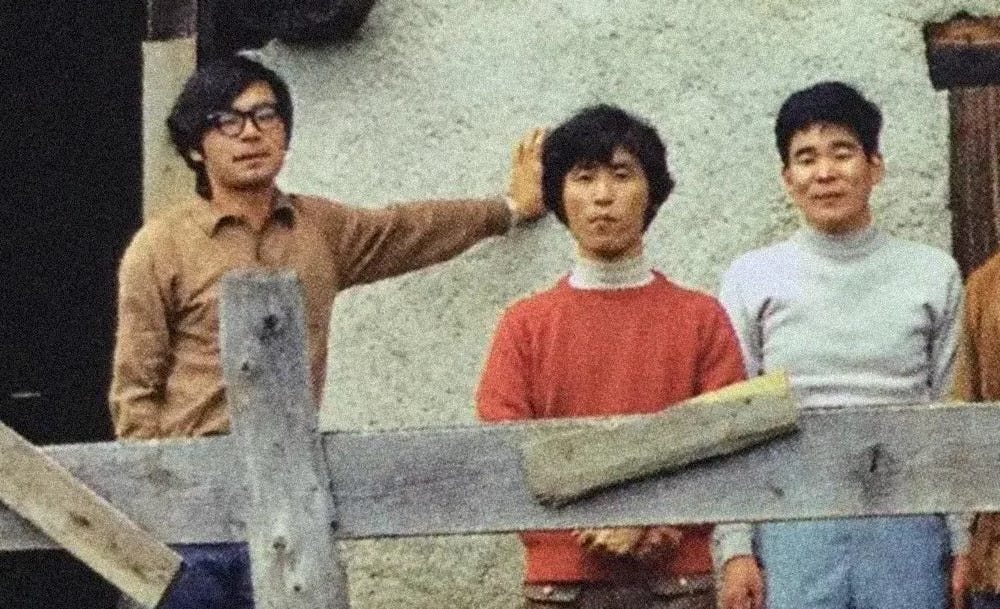

In 1978, Hayao Miyazaki was in his late 30s — and right at the start of his directing career.

Studio Ghibli didn’t exist yet. Neither did the movies that made Miyazaki iconic. In fact, his whole approach to stories and characters was a bit different: simpler, zanier and more direct. He had a love for rascally heroes, damsels in distress, cartoon bad guys. Princess Mononoke (1997) was unimaginable back then.

There were foundations in place, though — core parts of Miyazaki’s style that stayed with him. He hinted at them during ‘78, when he named his two favorite works of animation: the Soviet Snow Queen and a film called Panda! Go, Panda! (1972).

Panda is a half-hour piece directed by Isao Takahata. It’s one of Miyazaki’s earliest projects — he was its writer and lead crewmember. For him, it was life-changing. “I have never had more pleasure as I worked,” he wrote in the ‘80s.1

Their film was intended for young kids, and the inspiration behind it was personal. The two of them had children the “right age” for this story, Takahata said. Another main Panda staffer, Yoichi Kotabe, was also a father. Animator Yasuo Otsuka (on the team as well) saw the film as “a gift for [their] children.”2

“When I didn’t have kids, I wanted to create things for myself,” Miyazaki explained. “When I had little ones, I wanted to create things to entertain them.”

And yet Panda didn’t only affect the kids in the audience. It laid groundwork for its team, too. Here, Otsuka argued, was “one of the foundations for the line that continued into Ghibli.”3

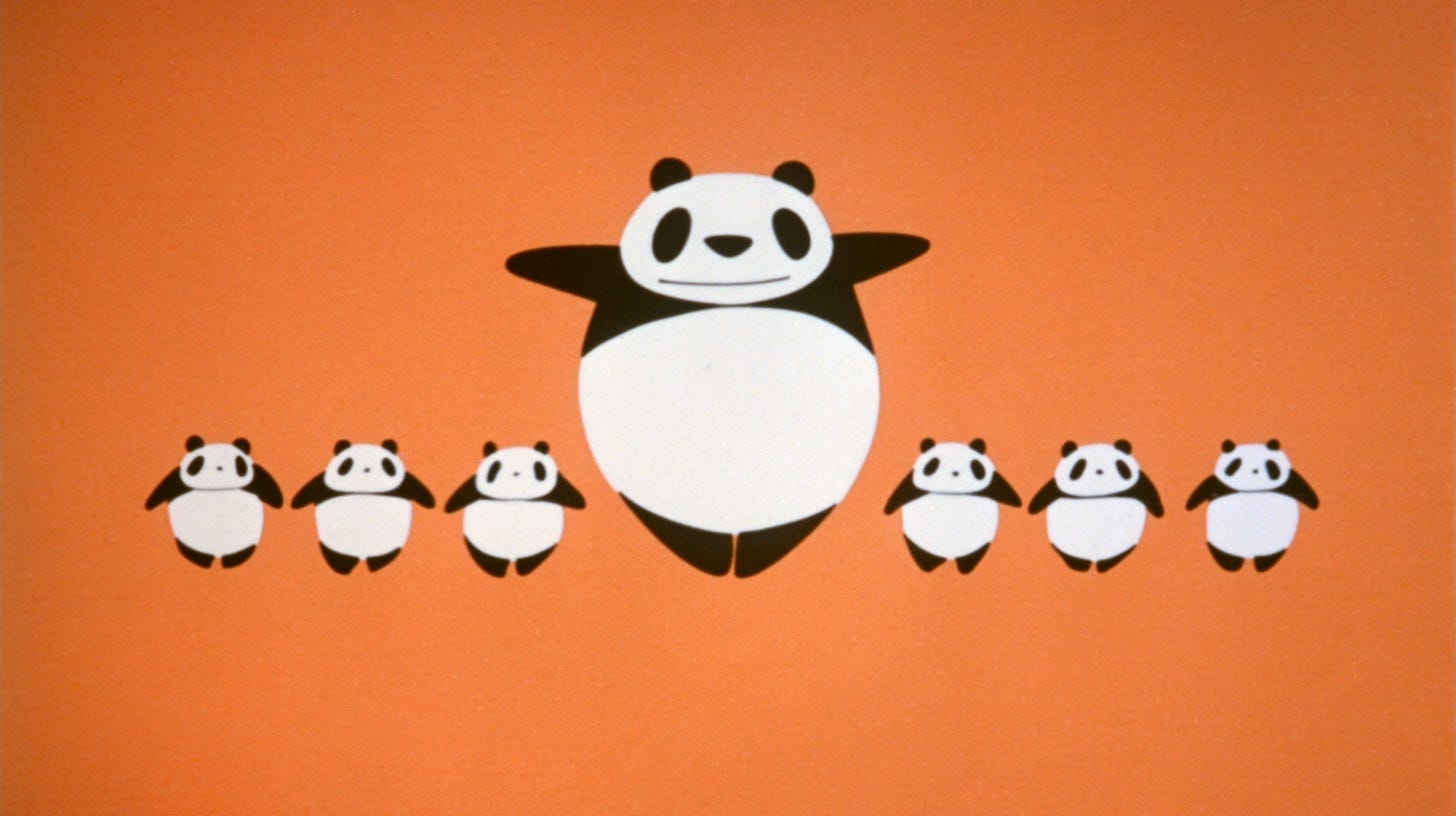

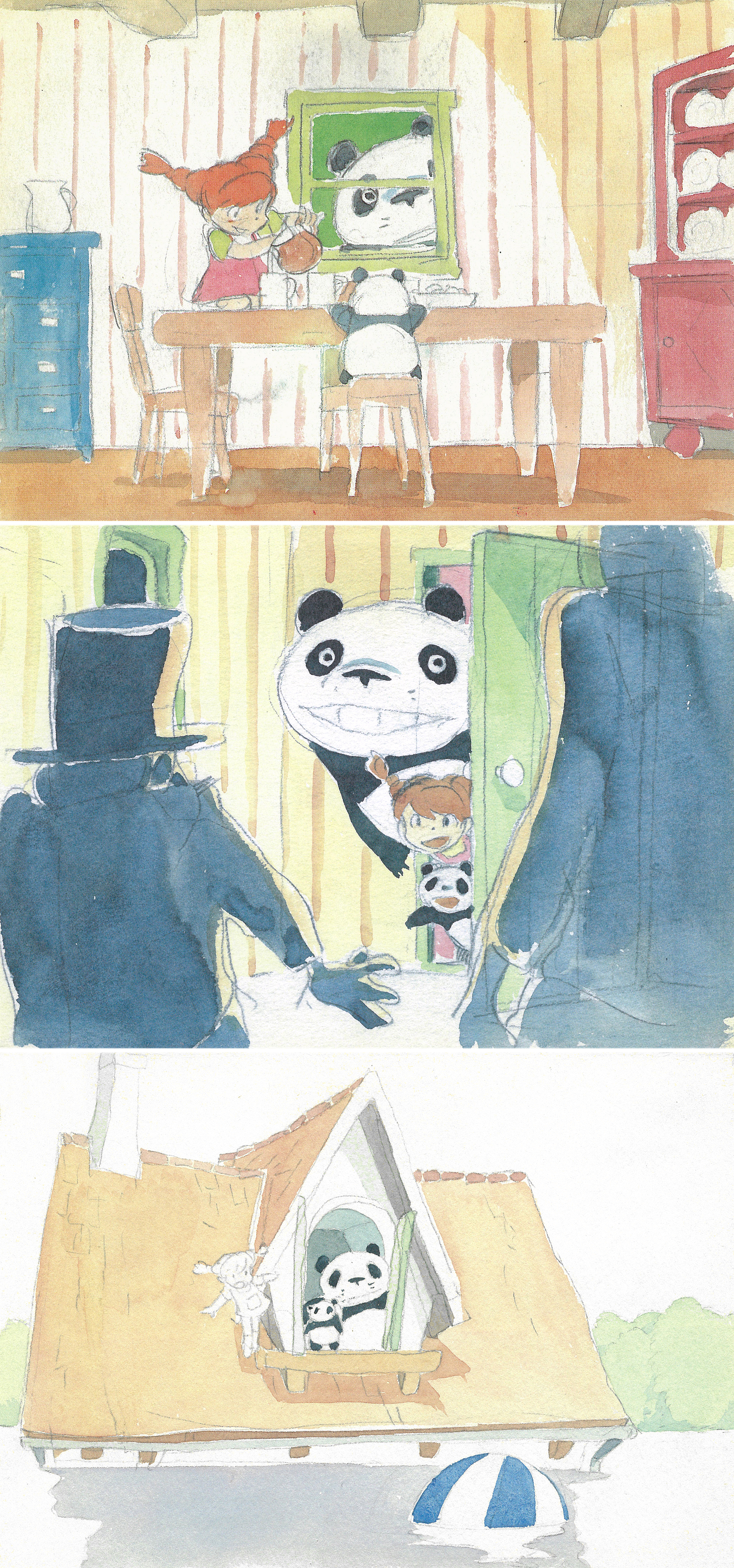

Panda! Go, Panda! is a slight story. A young orphan named Mimiko finds herself living alone in a cottage within a bamboo grove. Then a baby panda and its father arrive and make themselves at home. A few misadventures follow, but things stay fairly low-key. The film’s second part, Rainy Day Circus (released a few months later), is similarly light on plot. It’s really a series of events — mundane and extraordinary by turns.

That was by design. As Miyazaki wrote:

… this was not a story that began with a dramatic event and then unfolded (our aim was precisely to avoid such a structure) … Indeed, when it was written up as a script, it seemed extremely ordinary, and it would have been natural for anyone to worry if the material could be turned into a film. Yet I still believe that what we were aiming for was correct.

They wanted a new type of animated story. The point wasn’t an epic journey, superheroics or interplanetary conflict. Panda’s basis is day-to-day reality: frying eggs, hanging laundry, walking across the lawn. The fantastical parts are entrenched in a believable world — one with “a sense of presence,” as Takahata wrote.

We feel the existence of Mimiko’s cottage and classroom. These are concrete places, and characters live recognizable lives in them. Add a little magic — like a talking panda — and it makes the recognizable feel special again. The idea was to “idealize and clearly bring out the charm hidden in everyday life,” in Takahata’s words, so that children would notice the magic around them.4

Takahata and Miyazaki were fixated on thoughts like these — on grounding their work in reality. To Miyazaki, for example, the “most lacking part about animation at that time” was its inability to show everyday process in detail.5

They experimented along these lines as early as Horus: Prince of the Sun (1968), Takahata’s animated movie for Toei Doga. During 1971, their theories solidified into the Pippi Longstocking series that Takahata, Miyazaki and Yoichi Kotabe developed at the studio A Production.

Only Pippi wasn’t made. Despite their love for the project, author Astrid Lindgren turned them down. “So all the Pippi staff were depressed,” Kotabe said.

They got scattered to other A Production shows, among them the crumbling Lupin the 3rd project in ‘71 and early ‘72. Takahata felt that the decision to leave Toei had been a mistake. “Why did I move here?” he wondered as he worked on animation that had little to do with his own interests.6

A Production’s founder knew that his three star newcomers weren’t happy. Yasuo Otsuka, who’d joined the company before them, noted that there was an attempt to find an original project that would “make the most” of Takahata, Miyazaki and Kotabe. That project became Panda.7

The plan to tell a story about pandas was Takahata’s. They weren’t widely known in Japan yet, but he was a self-described panda fan: he “already had various things like photo books from foreign countries,” including one of the famous Chi Chi.

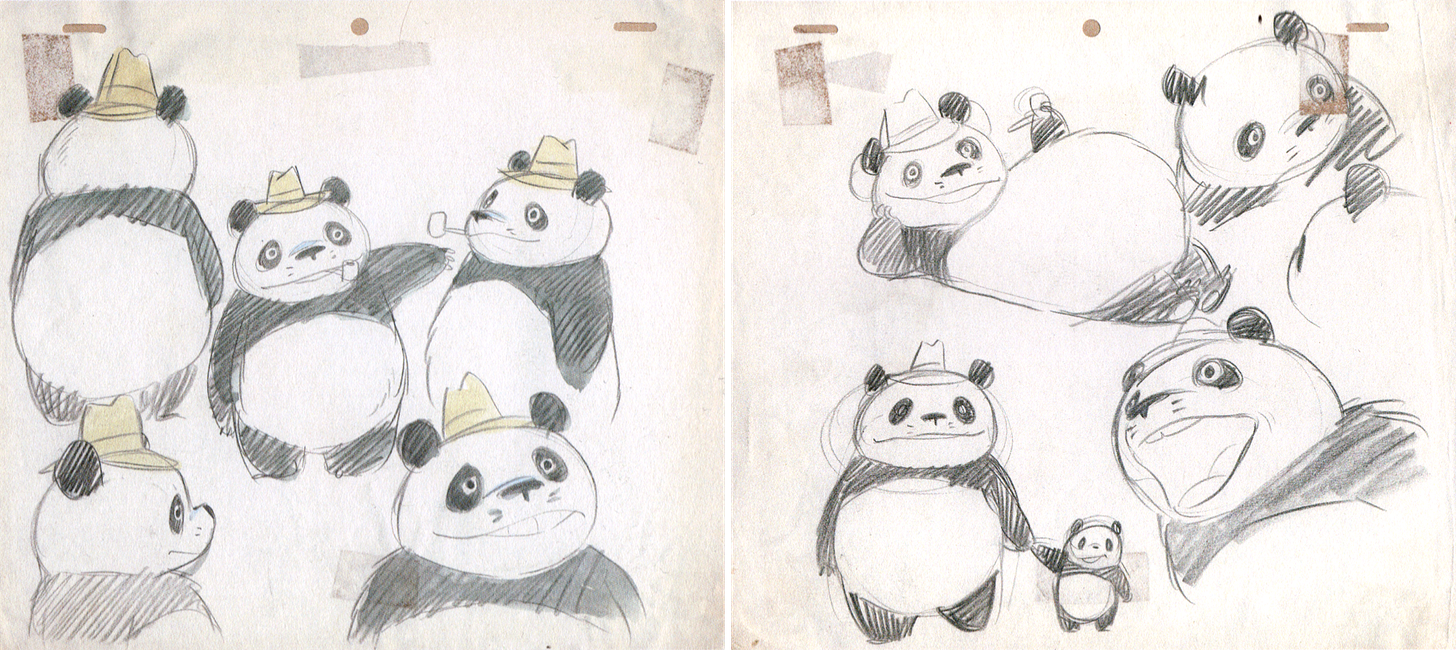

“We wrote the proposal in one night,” recalled Miyazaki. He was immediately drawn to it: “when I read the wording of the proposal that Isao Takahata-san had quickly written up, I felt my heart swell in anticipation — I could create a wonderful world.” One early sketch page shows Mimiko and two small pandas with the caption, “Beauty (?) and the Beast.”8

Their pitch was shelved by management. Months later, though, the situation changed. A Japanese zoo received two pandas from China in October ‘72 — sparking a “panda boom.” The film was greenlit, and it needed to be ready in a “shockingly short amount of time” to capitalize on the fad, Takahata said. It would debut that December.

They couldn’t do a lot of deep planning — Panda was a frenzy of creation in the moment. “Paku-san [Takahata] and Miya-san worked furiously, fueled by their anger [about Pippi] that had nowhere to go,” wrote Kotabe.

The rubble of Pippi was the project’s raw material. Their experience with the series was still fresh, and they wanted to see its ideas through. Mimiko was based on a design sketch of Pippi — both characters are upbeat orphans who manage households alone.9 Pippi’s cottage was essentially reused. And the old plan to depict and elevate everyday life found its realization in Panda, making this film “the first time we were able to completely hammer it out,” Takahata said.

The pandas’ initial designs came from Miyazaki, who again pulled from earlier ideas. “Miyazaki-san had been developing this dumpling-like, stuffed-animal-like character for a long while, and he tried using it for the first time here,” explained Otsuka.10 Much later, that character evolved into Totoro.

During the ‘80s, Miyazaki discussed the origin of his furry, supernatural giants:

The Kenji Miyazawa story I like best is Donguri to yamaneko (The Acorns and the Wildcat). Even after reading it, I couldn’t figure out what the wildcat was. And it wasn’t necessary to know. When I saw the illustration, I didn’t like it at all. I thought it was wrong to have such a small wildcat. In my mind I had imagined a huge, two-meter tall wildcat just standing there, looking off in the distance, with small acorns running around screeching at its feet. When I thought of the wildcat vacantly standing there, I fell in love with that world. Actually, I was quite disappointed when I first saw a fox. … Having often heard as a child from my mother about raccoon dogs and foxes bewitching people, and about foxes that turn into humans and ride on horses and are caught as they try to eat deep fried tofu, I assumed they were much larger animals. But they weren’t.

That was why when I made Panda! Go, Panda! I made sure they were huge and just dazedly standing there. I am Japanese after all. We have the term koriko or “being clever” (on a small scale). We also have the term taigu (great fool) for incredible stupidity. I think Japanese people like a bottomless, enormous foolishness, especially in people who become important.

In composing Panda’s world, Miyazaki sketched quickly from his own memories. Mimiko’s town and home are in part images of the past. “Houses with wooden fences and cosmos flowers growing in the garden are scenes from my childhood,” he said. The train station toward the start is an idealized version of one he knew in Saitama Prefecture.11

None of it was exactly like his early life, though. He embellished things, made them better than reality. The world of Panda is “Japan as it might have become, the landscape showing streets that should have been, the scenery that even now has the potential to appear the way we depicted it,” Miyazaki wrote. It was, again, the everyday idealized.

He and Takahata worked out the storyboard while staying at a secluded inn, somewhere in Tokyo’s Kagurazaka neighborhood. They built from Miyazaki’s large number of Panda concept sketches, themselves based on his sketches for Pippi. He was a nonstop current of ideas, characters and locations in those years. Still, he wasn’t yet a director: it was Takahata who brought the film together.12

“At the storyboard stage,” Miyazaki wrote, “the pictures I had drawn for the script were expertly arranged by Takahata. The features I subconsciously had in mind for the characters were transformed into the language of film. This was very satisfying to me.”

Takahata commanded the team’s respect, according to Kotabe — who served as an animation director here. “However, he often found fault [with my work], so it felt like being trained,” he noted. Takahata had a standard, and he worked with the team to reach it.

The atmosphere on Panda was deeply positive nonetheless. It was a project that grew from the camaraderie and friendship between Miyazaki, Takahata, Kotabe and Otsuka. They were excited.

Management, less so. The film was quiet, and it made the bosses nervous. Higher-up Yutaka Fujioka asked questions like, “Is it really okay for it to be so peaceful?” As Takahata said:

… Japanese animation at the time went at a very fast pace. Because children’s ability to steadily watch wouldn’t last that long. We were told we had to make rapid noises and make things intense and detailed. So, this kind of leisurely film, where it’s kind of soothing and relaxing, was something that everyone thought would be difficult to present.

The team suspected that children would be enthralled by this world they’d made, but they didn’t really know. Not until it reached theaters.

After the chaotic sprint to finish Panda, the four of them got to see it — Takahata and Miyazaki with children in tow. “I went to the movie theater with my son and niece. It was shown with a Godzilla movie,” Miyazaki remembered.

The kids in the audience weren’t especially taken by Godzilla: they spent a lot of the film ignoring the screen and playing. Panda was a different story. “They were really focused when they were watching. Not only that, they’d really laugh where they were supposed to laugh,” Takahata said.

Most moving for the team was the reaction to the closing moments. “[A]ll the kids sang the ending song together and the whole theater joined in chorus,” Kotabe said. “I’ve never been happier than I was at that moment.”

For Miyazaki, it was defining:

At the end they sang along with the theme song. I was thrilled. I recall feeling very happy at the sight of those children. And I think it was because of the support of those children that I decided on the kind of work I’d do from then on.

Goro Miyazaki was among the kids in the audience. He’d been looking forward to the Godzilla film — but “the only thing that remained in my mind was Panda! Go, Panda!” he remembered as an adult. Although he saw it just once, it stayed with him for decades. “It was one of my happiest memories of my childhood,” he said in the 2000s.13

Before long, Panda disappeared into obscurity. Based on comments from Takahata, A Production’s effort to cash in on the panda boom seems to have failed.

But the team didn’t forget Panda or its sequel (made on another tough deadline). The films were an origin point for Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s mature styles, in many ways. They’re raw and early, but so much is here: the quiet moments, the “sense of presence,” the focus on everyday realities.

Even in the wider credits, you see signs of what was ahead. Yoshifumi Kondo (director of Whisper of the Heart) animated the jump rope sequence, wowing Otsuka. Michiyo Yasuda (Ghibli’s main color designer) was in the ink-and-paint department. Kazuo Oga (art director of Totoro) was a background artist on the second Panda film. When Miyazaki pitched Totoro to him in the ‘80s, Oga felt something familiar. As he said, “I remember thinking, ‘Ah, Panda! Go, Panda! was also a world like this.’ ”14

Plenty would shift in the years to come. Takahata soon lost interest in chasing the cartoony and idealized parts of Panda. Miyazaki spent a few years going all-in on those elements, only to move toward stranger, darker work like Nausicaä. He said in the early ‘80s that people asked him to return to the Panda style, but he couldn’t do it: his children were older, and his focus had changed with them.

But Panda was still there for its creators. It was still special to them. As they wrote in the ‘90s, addressing children born way after the singalong in the theater:

This is a film we made over 20 years ago, but we still consider it a very important work for us. That’s because this film became the basis for many of the works we’ve done since.15

2 – Newsbits

We lost David Lynch (78), whose legendary career had a long-running undercurrent of animation.

The small Flow continues to do big numbers. It’s one of the most-attended movies ever in Latvia, and more than 1.5 million people have gone to see it just between Mexico and France.

Australian animator Alex Grigg dropped a new video on the art of anticipation and overshoot.

Before The Thief and the Cobbler, animator Richard Williams was working on a film called Nasruddin in Britain. Now, researcher Daniel Aguirre Hansell has created a compelling animatic for a scene of its surviving storyboards.

Also in Britain, a stop-motion film worth your time: Shackle, an impressive use of outdoor filming.

In France, The Character of Rain is finally due in theaters this June, and there’s a new teaser.

As China deals with the influx of Westerners on RedNote, Anim-Babblers has looked into views toward Chinese animation abroad.

Animenomics reports that the American distributor GKIDS sold to Toho for $140 million. The company brought The Boy and the Heron stateside in 2023, and was purchased last year — but the dollar figure is new.

One more British story: the BAFTA nominations are out. Flow has two, and the short film Adiós, which we enjoyed a lot last year, is up for an award.

Lastly, for our first Thursday issue of 2025, we wrote about one of our favorite cartoons: The Juggler of Our Lady (1957).

Until next time!

Miyazaki named Panda and Snow Queen his favorite animation in Manga Shonen (October 1978). The quote about his enjoyment of the project comes from “What the Scenario Means to Me” in Starting Point 1979–1996, used throughout.

Takahata’s quote about the “right age” comes from his 40-minute interview on the GKIDS Blu-ray release of Panda, one of our main sources. Otsuka’s line is from the Panda section of Drawings Covered in Sweat: Latest Revised Edition.

Miyazaki’s point about entertaining his children was made in the book Hayao Miyazaki Image Board (1983). Otsuka spoke about the line from Panda to Ghibli in the Panda section of Yasuo Otsuka Interview (大塚康生インタビュー, 2006), cited several times.

From Takahata’s essay in Animage (August 1981), a key source.

From Miyazaki’s interview in The Phantom Pippi Longstocking.

Kotabe’s point about depression is from The Anime (December 1982), via the Anim’Archive. Takahata mentioned feeling that he’d made a mistake in his Phantom Pippi Longstocking interview.

See Otsuka’s book The Aspirations of Little Nemo, used a couple of times.

Miyazaki’s quote comes from Starting Point (“Panda in Process”). Elsewhere, we used “Panda! Go Panda! Creator’s Message” and “Totoro Was Not Made as a Nostalgia Piece” from the same book. For the early concept sketch, see Seiji Kanoh on Twitter.

See Kotabe’s section of The People Who Built Japanese Animation.

Otsuka mentions this in Yasuo Otsuka Interview.

Miyazaki’s quote comes from Future Boy Conan: Film 1/24 Special Issue (1979).

Kotabe mentioned Kagurazaka in the Panda section of Yoichi Kotabe: Legendary Animator, used a few times.

From the interview with Goro Miyazaki on GKIDS’ Panda Blu-ray.

From the book Kazuo Oga Art Collection. Translated by Toadette.

Wow - a fantastic dive into Ghibli history! Have you seen the animations Miyazaki did for Takahata's live-action The Story of Yanagawa's Canals?

Props to your thorough research in composing a humble, sincere and yet humbling sort-of origin story for these minds -- it is very dear to me now!! ^_^