What Makes 'Abel's Island' an East Coast Classic

Plus: a Czech treasure and the world's animation news.

Welcome back! We’re here with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And this is the slate today:

1 — how the classic film Abel’s Island came to be.

2 — animation news from all around the world.

3 — a beautiful work by “the mother of Czech animation.”

We publish Sundays and Thursdays. If you’re new to the newsletter, you can sign up to receive our Sunday issues in your inbox for free, every week:

With that out of the way, let’s get moving!

1. Abel’s Island, New York

East Coast animation is its own animal. Although California is justifiably hyped, as the place of Disney and Pixar (to name just two), there’s a rich and underexplored tradition of cartoons on the other side of the country.

It’s where Faith and John Hubley, who won the first Oscar for an independent animated film, made their home in the 1950s. Their New York studio, and several of its rivals, evolved East Coast animation into something that artist Richard O’Connor once called “an easily identifiable yet qualitatively indescribable art form.”

When he wrote those words, O’Connor was talking about Abel’s Island (1988).

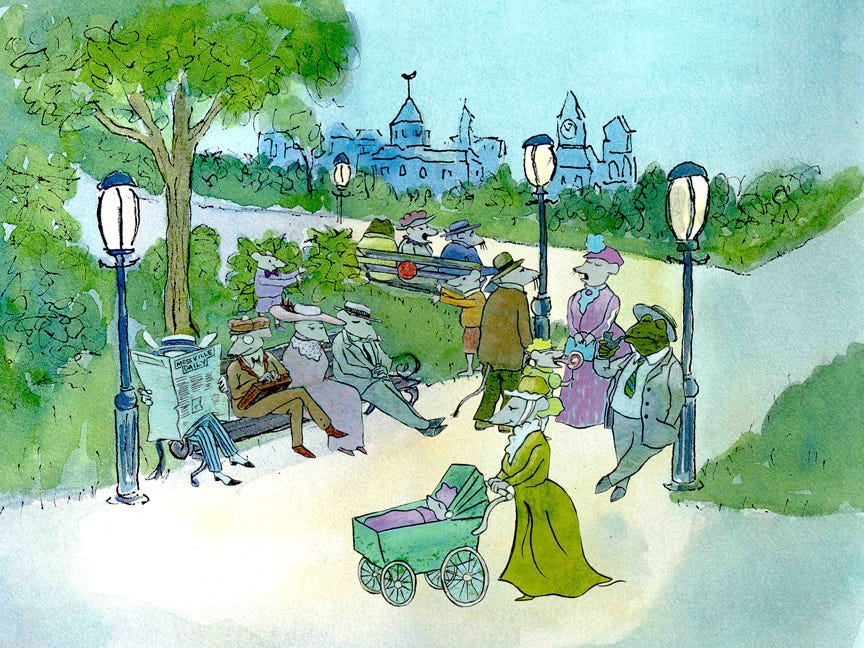

Made at a time when American cartoons had a dodgy reputation, Abel’s Island defies the stereotypes. It’s quiet. It’s sensitive. It feels handcrafted — all loose shapes and expressive lines. Based on a children’s book by William Steig (author of Shrek), it looks like his artwork brought to life.

In Abel’s Island, a wealthy mouse named “Abelard Hassam de Chirico Flint” gets swept by a storm away from his wife and onto a small island in the middle of a river. Trapped for a year, he learns to survive in the wild. Tim Curry is one of the only voice actors in the film — he gives a world-class performance as Abel.

Behind the whole project was Michael Sporn, a giant of the New York scene. He worked at the Hubley Studio in the ‘70s before running his own in the ‘80s. The specialness of New York animation wasn’t lost on him. As Sporn said while making Abel’s Island, “I have an affinity for the work that’s done here; it has a different feel, somehow.”1

A lot of that came from the artists on the East Coast. And Michael Sporn Animation, like the Hubley Studio, encouraged them to be unique. Sporn’s animator Lisa Crafts once told him:

You treated each animator as a director, and gave us a lot of latitude, and the films reflected that generosity. I got up to speed by the time we worked on Abel’s Island, and felt each scene you handed me was my personal work, and put that kind of spirit into it.

According to Sporn, the whole film happened because he sent a Christmas card to an animation producer, Giuliana Nicodemi. When they met, Sporn recalled, “She asked me off-hand if I had any projects I was looking to do, and I named this book.”2

The result was an inexpensive licensed project, like so much of Sporn’s work. Abel’s Island is a half-hour short, made for VHS. “Giuliana was able to get Random House Home Video in on the deal to help finance it,” said Sporn. The budget was “relatively low” (his films cost between $135,000 and $300,000 at the time).

Sporn and his team inhabited a lane that many associate with rushed, poor cartoons — but they tackled Abel’s Island like independent artists.

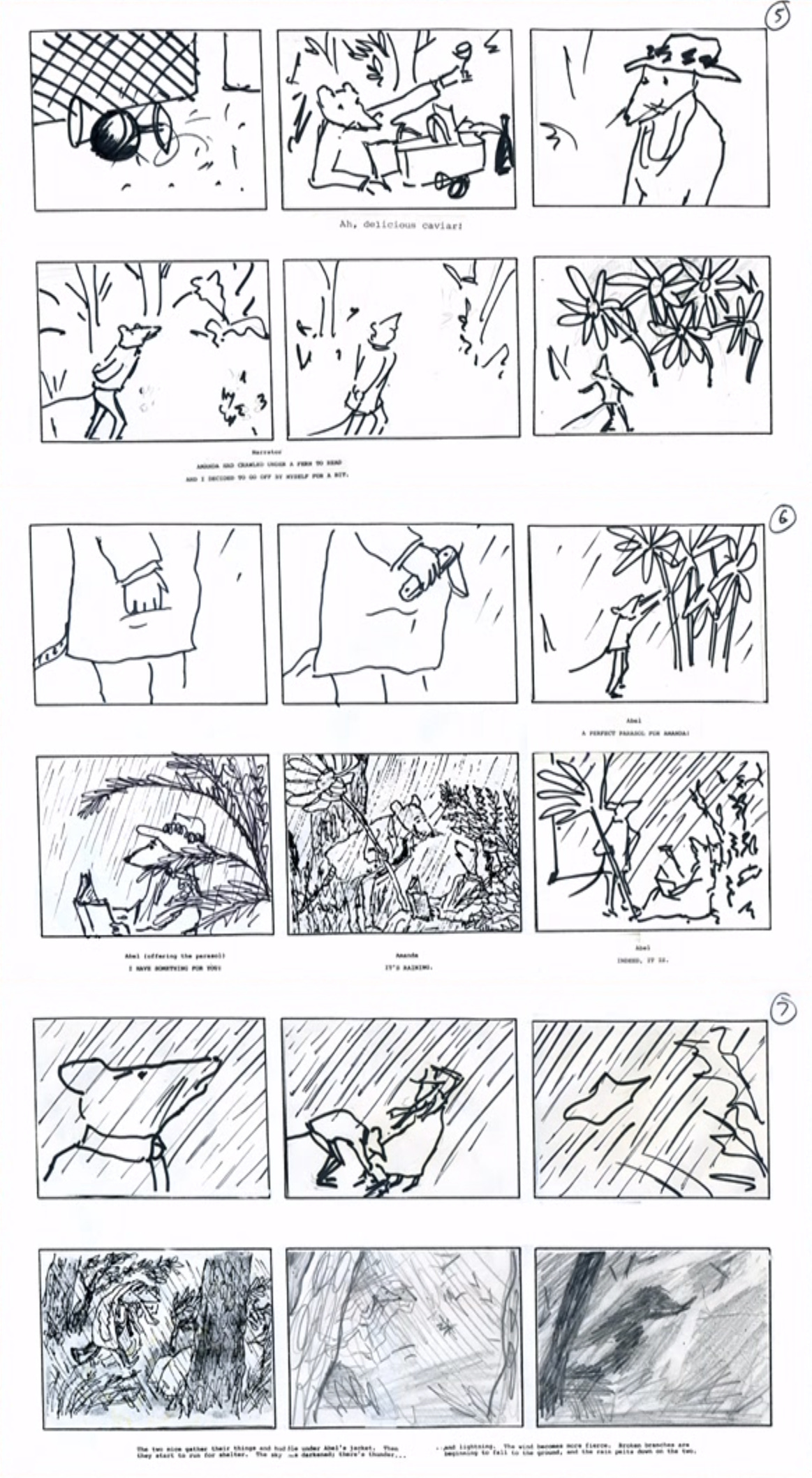

“We set out to do the artwork for the film more like artwork, rather than animation art,” Sporn noted. That meant watercolor backgrounds. And, in a move straight from the Hubleys’ playbook, they drew the characters on paper and colored them with watercolors and magic markers — then cut them out and pasted them onto cels.

A small team made Abel’s Island. Each artist had a lot of responsibility — and a lot of room to create.

Bridget Thorne art-directed the film, painted its backgrounds and co-storyboarded the entire thing with Sporn. Her job was made even bigger by the nature of Steig’s book. “The more than 120 pages featured fewer than 20 black-and-white spot drawings,” Sporn wrote. That made for a paradox: to capture a Steig look, they had to get creative.

They combed through Steig’s other books, cobbling bits and pieces together into what Sporn called “the best version of a William Steig film” — swiping a winter scene here, an owl there. Thorne’s job on the backgrounds and art direction blew Sporn away.

The animation blew him away, too. Seeing the unrestrained freedom of the faces, and even the walks, it’s easy to agree. At the time, the top East Coast animators often liked to improvise parts of their work, and Sporn supported it at his studio. (These were “storytellers as well as animators,” to quote New York animation vet R. O. Blechman.)

Sporn kept a close eye on his animators, but he made sure that they got “very loose layouts” and “as much control as they want[ed]” within the limits of the storyboard. To see the result, read what Sporn had to say about the animation of Lisa Crafts:

The humanity she brought to the character of Abel […] just knocked my socks off. When he found a timepiece on the island and brought it back to his camp, he said the ticking reminded him of his wife’s heart; he felt it brought him closer to the partner he’d been separated from. Lisa went a step beyond the layout by having Abel physically embrace the watch. There was just so much warmth in that gesture; it solidified the scene and said so much about the character.

Tissa David, one of the world’s best animators and a New York artist well known to “add things” (Blechman’s phrase), handled much of the first part of Abel’s Island. As Sporn wrote, “She established our character.”

Another major name on the film was John R. Dilworth, who drew the layouts and animated Abel’s battle with an owl. (He’s better known for going on to create Courage the Cowardly Dog at his studio Stretch Films, also based in New York.)

Despite the low budget, limited staff and high ambition of Abel’s Island, it wasn’t a nightmare. “This film was a complicated problem that seemed to resolve itself easily and flow onto the screen without much struggle,” Sporn wrote later. That applied even to recording Tim Curry’s voice. Sporn set aside three days for taping and editing. Curry was so good that it took “a grand total of three hours.”

The worst trouble on Abel’s Island was a falling-out, for business reasons, with Steig’s musician son during production. Even then, Sporn’s impression was that Steig “was pretty happy with it at the end.”

Abel’s Island went on to nab an Emmy nomination. Sporn saw it as one of his finest films, and it continued a winning streak for his studio. Even before Abel’s Island was finished, the Los Angeles Times claimed that Sporn was “revitalizing the stagnant New York animation industry almost single-handedly.”

Yet so much of what makes Abel’s Island great comes from the fact that it leans into what was already great about East Coast animation. The film is a showcase for it — the personal artistry, the improvisation, the animation techniques that change to suit the project. The way it does a lot with a little money.

At the time, the best East Coast studios were doing work like this — like Faith Hubley’s solo films, or Blechman’s The Soldier’s Tale. If you’ve ever watched one of the classic Sesame Street cartoons from that era, there’s a good chance it was made on the East Coast. This animation was far from splashy, but it was alive.

And Michael Sporn was among the best in the scene. Abel’s Island is a wonderful example. It’s another paradox: so much of the film’s uniqueness comes from Sporn’s firm roots in tradition — a tradition that Abel’s Island kept moving forward.

2. Global animation news

The week in Netflix

No animation story this week overshadowed the one about the crumbling of Netflix Animation. The studio still exists — but the situation there is “deeply chaotic.” A number of top people are out, including Phil Rynda (Gravity Falls). An adaptation of Jeff Smith’s comic Bone is dead.

There’s talk of data-driven decisions, poor marketing and a loss of creative freedom. Plus, endless requests to make projects more like The Boss Baby: Back in Business — which Netflix considers “the ideal of what an animated series on the platform should be.”

Responding to the situation on Twitter, writer Amalia Levari (Centaurworld) remarked:

Before the “make it like Boss Baby” notes became ubiquitous, there was a short window where they championed visionary creator-driven shows. Warping their algorithm to torpedo that approach did so much damage, because cartoons are made by… people. A ton of brilliant, good people.

Elsewhere, Lauren Faust discussed the possible future of her canceled series, Toil and Trouble. Jeff Smith put out a painful comic about why he’s never agreeing to another animated Bone. And artist Grace Kraft tweeted, “The project I was on was one of the many casualties to this algorithmic nonsense. I’m still salty.”

It all comes as Netflix’s stock races to the ground. The company is bleeding users — not least because it just cut 700,000 Russian subscribers. The recent price hike cost almost as many people in North America.

At the same time, business continues as usual for many Netflix affiliates in animation. Jorge R. Gutierrez (Maya and the Three) is hard at work on his new feature film I, Chihuahua — yet he found himself bombarded with questions this week about the “closure” of Netflix Animation.

That’s just one of many ambitious animated features that Netflix has in the pipe. Animation Magazine recently reminded us that these include Pinocchio by Guillermo del Toro, Wendell & Wild by Henry Selick and Aardman’s sequel to Chicken Run. Most exciting, for us, is My Father’s Dragon by Cartoon Saloon in Ireland. Its first image appeared this week. Directed by Nora Twomey (The Breadwinner), it looks good.

It remains to be seen how Netflix responds to the current crisis — and whether it moves toward more projects like My Father’s Dragon, or decides to chase numbers into oblivion.

Best of the rest

American animation legend Eric Goldberg says that Disney is “training up a new generation” of 2D animators. A bunch of 2D projects, including features, are under consideration.

In Japan, Toshio Suzuki of Studio Ghibli designed three lemon sibling characters for an entertainment agency. Hayao Miyazaki named them Retarou, Monta and Nnko.

Companies in Ukraine are banding together to create a support fund for domestic TV programming, including animation. It’s looking for money from the likes of Disney and Netflix.

In Russia, a funding program for arts and culture will accept projects on themes tied to pro-Russia propaganda. A “Made in Russia” initiative, praised by the head of Soyuzmultfilm, will promote Russian products. And a bill in the works could let Russian firms violate foreign copyrights on films, music and more.

One of India’s best animated series, Lamput, is coming to HBO Max.

American feature Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse has been delayed to mid-2023.

Japanese studio Toei Animation set up a training course that also pays budding animators. One analyst notes that in-house programs like this one are getting popular as “a countermeasure to the growing shortage of animators in Japan.”

Lastly, we dove deep into the making of On Love, one of Cartoon Saloon’s most gorgeous and underrated pieces ever.

Thanks for reading today’s issue so far! We hope you’re enjoying it.

The last section of this newsletter is for members (paying subscribers). Below, we explore one of our favorite Czech animated films — The Blue Apron by Hermína Týrlová.

Týrlová is often called “the mother of Czech animation.” Films like this one are the reason. We look at The Blue Apron’s background, and at why it’s absolutely worth watching today. (Luckily, there’s a wonderful restored version.)

Members, read on. We’ll see everyone else in the next issue!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.