Winning an Oscar, Losing Your Way

Plus: animation news.

Happy Sunday! The Animation Obsessive newsletter returns with a new issue — we’re excited to share it.

First, though, we want to mention that last Sunday’s issue (our interview with Jim Capobianco) got featured in Substack Reads. We’re very grateful for the shout-out. Welcome to our new readers!

With that, here’s the agenda for today:

1️⃣ On the Oscar-winning House of Small Cubes (2008).

2️⃣ Animation news worldwide.

Just finding us? We do this every week. You can sign up for free to get our Sunday issues right in your inbox:

With that out of the way, here we go!

1: When success isn’t enough

For the past three or four decades, Japan has been an animation superpower. It’s only the Oscars that haven’t really accepted it. The Academy started to give out awards for animation in the ‘30s; just two Japanese entries have won them to date.

The first was Spirited Away (2001) by Hayao Miyazaki, which took the feature category a little over 20 years ago. The second winner, the sole animated short from Japan ever to get an Oscar, was Kunio Kato’s The House of Small Cubes (2008).

The Miyazaki win was historic. Kato’s was, too. Miyazaki occupied the mainstream of Japanese animation, but Kato came from the alt-animation underground. The House of Small Cubes is non-commercial, un-anime. Suddenly, it became important by default: Kato and his film had made Japanese history. Nothing could take that away.

Before Small Cubes, Kato wasn’t a huge name. He did contract work and experimental projects like The Diary of Tortov Roddle (2003), which we covered in January. These got attention from people in the know, but the response to Small Cubes was different. A little before Kato’s Oscar win, a journalist asked him if he’d expected the hype. “No, not at all,” he replied. “This has all come as a complete surprise.”

Over time, though, that surprise soured into frustration and confusion.

Small Cubes is an excellent film — as you can see for yourself, embedded below. Yet Kato was never that happy with it. Finishing the project, he said, he was “only left with a lack of a sense of accomplishment.” Then it got the Oscar anyway.

As the Asahi Shimbun reported in 2019, “This work that he was totally unconvinced by won the world’s highest award, and the disconnect confused him.” Kato was in his early 30s. In a sense, he’d peaked young with a film he found lacking.

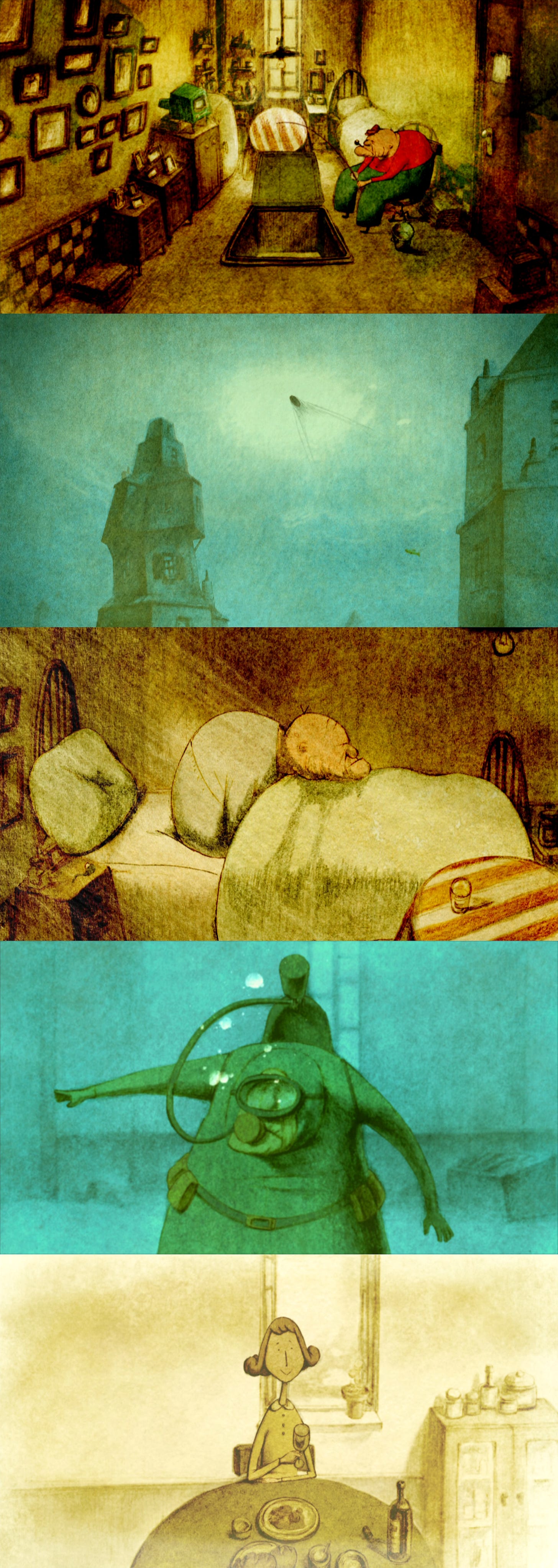

The House of Small Cubes is about an old man living in the middle of the ocean. Water surrounds his house and those of his neighbors. It keeps rising. People either build their homes higher, stacking room on top of room, or they’re forced to move away. The old man keeps building.1

The thing is, the whole structure doubles as a kind of time capsule. Each floor represents a past stage of the man’s life, left behind. He scuba dives down through them — revisiting his memories, from the nearest to the most distant.

It’s a deeply melancholy film. A beautiful film. Kato has always excelled at sinking the viewer into an atmosphere and world, and Small Cubes is no exception. Like with Tortov Roddle, there’s a quiet, whimsical, surrealist, quasi-European style to it that brings to mind Professor Layton (Kato did it first). The visuals and music pull you in.

But the process of making Small Cubes dragged Kato well outside his comfort zone.

The idea for the film dated back to his student days, to his second year at Tokyo’s Tama Art University. He wasn’t into animation then — he was studying graphic design. For a class, he did a painting of box-shaped houses arranged into stacks. “I think it was a surrealist painting assignment,” he told the Asahi Shimbun. The teetering buildings symbolized a family’s “instability.”

This concept stayed with him for years, he said. He wanted to turn it into something.

In Kato’s third year at Tama, he discovered the world of animation, falling in love with Mark Baker’s The Hill Farm (1989). It’s an early film by the co-creator of Peppa Pig, and it became a guiding influence for Kato. Out of college, he joined the Tokyo production house Robot, made Tortov Roddle and started to get known.2

Around late 2006 or early 2007, Robot offered Kato a slot in an anthology for young directors, titled Pieces of Love. The producer asked him for “a work that will move people in 10 minutes.” Although the other films in Pieces of Love were live action, Kato stayed with animation. His project would become The House of Small Cubes.

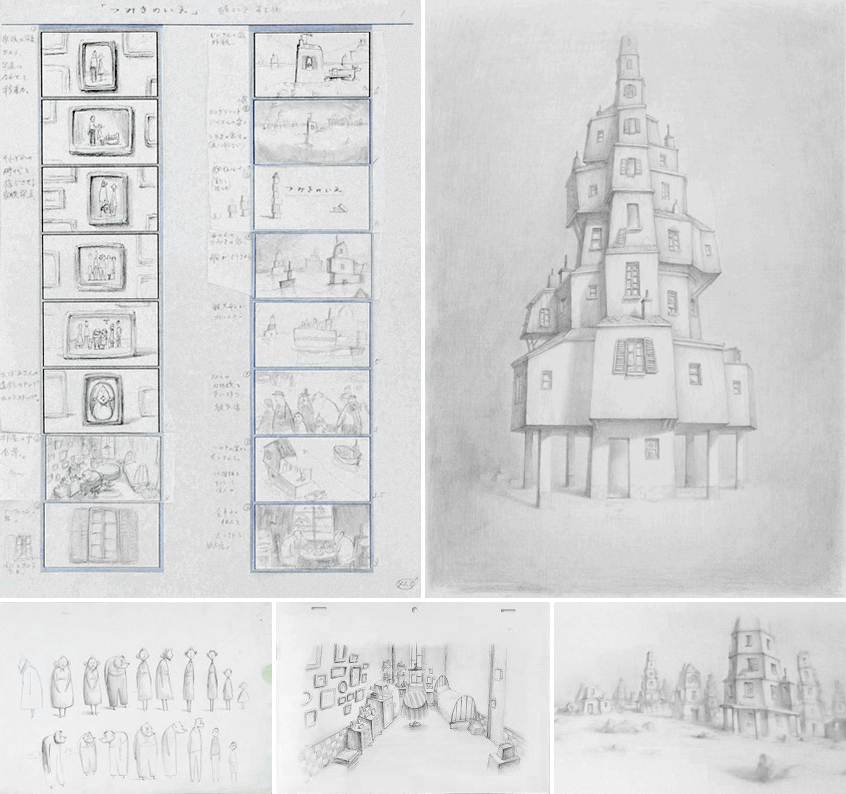

To come up with his film, Kato partnered with screenwriter Kenya Hirata, a co-worker at Robot. They sifted through Kato’s old art and ideas, and the cube houses won. Kato had already developed the concept beyond the version from school: the buildings were now partially submerged, with hatches in the floor that led to an underwater world below.3

It was more of his signature surrealism. But it got the gears turning for Hirata. “When I showed it to Mr. Hirata, the idea of cubes stacking up like mementos came up,” Kato remembered. Hirata developed a plot outline: an old man descending into his memories.

They collaborated to create the story, discussing it constantly. As Kato said:

When I showed him the first illustrations, Kenya Hirata started writing the story. During this writing process, we talked a lot: he wrote, I drew, but we continued to talk a lot. Little by little, we in fact composed it together. It didn’t happen all at once, but it was truly based on discussions and confrontations of points of view. We arrived at this result by truly working together.

Eventually, they settled on a plot and lead character. About the old man, Kato said, “Stacking up the cubes on top of each other is the only thing he can do. He needs not only memories to do this but also pride, ego and resignation or determination.” They left the old man’s emotional state vague: despite the sadness of the film, it’s open to interpretation whether he himself is unhappy. He’s chosen his life. Even if someone offered the man another place to live, Kato argued, he most likely wouldn’t go.4

“We spent four months developing the story,” Kato told AWN. By comparison, his earlier projects were more like two-to-four months total. Already, The House of Small Cubes was getting bigger and more ambitious than anything he’d done.

Kato had worked with tiny teams before — Tortov Roddle was mostly his own project, barring things like the soundtrack by Kenji Kondo. On the other hand, Small Cubes had a crew of 15 or 16. When full production started in May 2007, Kato was saddled not just with endless drawing, but with leading.

He remembered it this way:

I realized how difficult it is to share an idea. I’ve never been a good team player, and, because my working style is to create an idea as I draw, I have a hard time communicating well with people I’m meeting for the first time. If I draw a picture myself, I can tell them that this is what I mean, but it’s difficult to put it into words.

It was a big group on a short film — Small Cubes was planned to take just three months of production. That ultimately climbed to eight months. People, Kato included, were not happy.

A lot of it came down to Kato’s method. Small Cubes was animated in pencil, then scanned and colored digitally. But he leaned heavily into “the texture of the pencil,” he said. Every image had to get intense shading with physical graphite. This kind of rendering took “a tremendous amount of time,” and production started to drag.

In general, Kato felt like he couldn’t get the film to gel, despite his team’s efforts. It was a communication problem, the scale of the production, his own inexperience. His regrets arrived early — the lack of waves and detailed water animation, for example — and grew over time. After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, he came to believe that the quiet, calm sinking of the world in his film was an empty fantasy. It crushed him.

But the success of The House of Small Cubes was immediate. After a year in the planning and making, it started to sweep the festival circuit in 2008. It got major awards in Hiroshima. It claimed the Cristal grand prize at Annecy. In early 2009, it got its Oscar nomination — and Kato was invited to tour America’s animation industry for a few weeks, which he did.

Then, that February, he won.

Kato was extremely nervous when he went up to accept his Oscar: he knew almost no English. But he had prepared a few things, just in case. “Thank you, my pencil,” he said, having thought of it in the shower not long before. Plus, in the lead-up to the ceremony, a producer with Kato suggested referencing the old Styx lyric: “Domo arigato, Mr. Roboto.” Kato used it on stage — it brought down the house.

Even in the Japanese press, the speech was a hit. But Kato was harder on himself. “Never have I wished that I’d properly studied English more than I did then,” he said in 2012.

At home, the Oscar led to a spike of attention around Kato and his work. He was all over the news. Sales of the House of Small Cubes DVD jumped from 3,000 pre-victory to 30,000 just a few days later. International attention poured in, too: people wanted to work with him.

But Kato was falling into a creative slump. More than anything, the win had demoralized him.

An exhibition planner named Daisuke Kusakari saw Kato after the Oscar, recalling that he looked like “a frightened child.” The pressure was on. It was hard to keep drawing. And Kato was caught between his own unforgiving standards and the inconvenient fact that everyone loved Small Cubes, this film that frustrated him.

To date, Kato hasn’t made another grand festival film like Small Cubes. There was no return to the Oscars. But he also didn’t give up. Slowly but surely, he found another way.

In fact, he worked with Daisuke Kusakari to enter a different field of animation. He got the chance to do experimental shorts for a gallery exhibition — so, he made Scenes (情景, 2012). It’s eight minutes of deeply personal, melancholy vignettes. You won’t find it online, but it was a breakthrough for him.

Handcrafted animation for spaces besides festivals and theaters has become Kato’s specialty. A year or two ago, he released a gorgeous animated short for a Frog and Toad exhibition (see snippets here) at the Play! Museum in Japan. He’s done commercials, too, like his collaboration with Studio Ghibli on an ad for Lawson convenience stores. It’s another standout.

Kato went back to what he liked: smaller projects, more on his terms. Big ones, he decided, weren’t for him. In 2017, he left Robot to go independent.

You could’ve seen it coming. As Kato said a few months post-Oscar, “I received a big award for The House of Small Cubes, the Academy Award in the United States, but I would like to create works that will be evaluated as good without being overly conscious of that.” His ambitions were humble. He didn’t think he could change the world, but he felt that he could touch viewers in some small way. That was his goal.

A few years later, in 2012, Kato told a French journalist that the Oscar had allowed him to travel and expanded his horizons — but it “didn’t ultimately change much for me.” It’s true in one sense: he didn’t hit the big leagues after Small Cubes. He didn’t really want to.

Even if Kato never comes around to it, Small Cubes is an amazing film with a well-earned fan base around the globe. Yet the world it opened up to him wasn’t for him. For a time, after the Oscar, he lost his way. After searching, he found it again.

2: Newsbits

Speaking of Tama Art University students, Chinese animator Xu Yuan talked to Wuhu Animator Space about her film Sewing Love, whose impressive and disturbing visuals have been drawing eyes online in China. See it on YouTube.

In Japan, director Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World) released the pilot for his upcoming film The Mourning Children, and it’s absolutely stunning.

Also in Japan, there’s a government push to get elderly drivers off the road. Hayao Miyazaki gave up his license last year, and word is that he’s just donated his old Citroën to be displayed at the Ghibli Park.

In America, Pixar’s Elemental is out on Disney+ — it’s a refreshing change of pace. (Also, the Japanese cult film Junk Head came stateside last month. Amazon has it on Blu-ray, and it’s streaming for free via the library service Hoopla.)

Meanwhile, Pixar animator Mariko Hoshi spoke to the Japanese site Natalie about her many years in American animation, from Shrek 2 to Elemental.

China’s animation blogs are reporting that the second season of Heaven Official’s Blessing is coming October 18 — but not in mainland China. While the first season was popular a few years ago, the show’s gay themes have put it in the crosshairs of government censorship policies instituted since then.

Also in China: the Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive released a never-before-public document from 1986. Written by the head of Shanghai Animation Film Studio, it lets us see inside the company’s early work with foreign countries.

In America, VFX staffers at Marvel Studios have successfully unionized with IATSE. The vote was unanimous.

In Lebanon, the studio “wezank” has climbed above a million subscribers on its YouTube channel Lila TV, focused on preschool animation in Arabic. Kidscreen reports that “the government is only able to provide an hour or two of electricity per day — a challenge [the] team has navigated by switching to solar power.”

Lastly, we explored storyboarding processes from around the world — including Isao Takahata’s setup on My Neighbors the Yamadas and Yuri Norstein’s on Tale of Tales.

See you again soon!

It’s often said that The House of Small Cubes is about climate change, and it definitely appears to be. Kenya Hirata sensed it from the first sketch and wanted to incorporate it into the story. But Kato didn’t feel the same way. As he argued, including a “big theme” at the outset would overshadow the film. His goal was to portray someone surviving against the odds — the setting is surrealist, rather than strictly allegorical.

From this interview and the book Japanese Animation: Time Out of Mind.

This is a lovely read. I will be sure to share with others. Thank you

Cubes - so glad to have seen it. Thankyou. It feels very similar to the masterful Dudok films. I have to admit I am a complete sucker for this kind of work.