Magic Paper

On the international art of cutout animation.

Happy Thursday! In this issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, we’ve brought a meditation on the beauty of cutout animation, the art of moving paper (and cardboard, and more) with stop-motion filming.

Cutouts don’t have a glowing reputation right now. Online, it’s not uncommon to see modern cutout animation written off — it’s become associated with rushed, low-cost cartoons. But this is a wonderful form with a deep history behind it, stretching back before animation itself.

It’s an international form, too. One that’s cropped up in countries around the world. And, each time cutout animation appears, it changes shape to suit the needs and tastes of the artists involved. Even more than cel animation, cutouts can adapt.

Today, we’re touching on all of this, and looking at how artists from Prague to Shanghai to Moscow have made cutout animation their own. Enjoy!

This week, we added an exciting new book to our library: the Czech anthology Animace a doba (Animation and Time). It rounds up articles and interviews on Czech animation that first appeared in the magazine Film a doba from 1955 to 2000.

The book is a 400-page treasure trove. Today, though, we want to focus on one tiny moment from it, tucked away in a 1983 interview with animator Stanislav Látal (1919–1994). He’s renowned for his work under puppet master Jiří Trnka in Prague. Cutout animation was one of Látal’s specialties on these films.

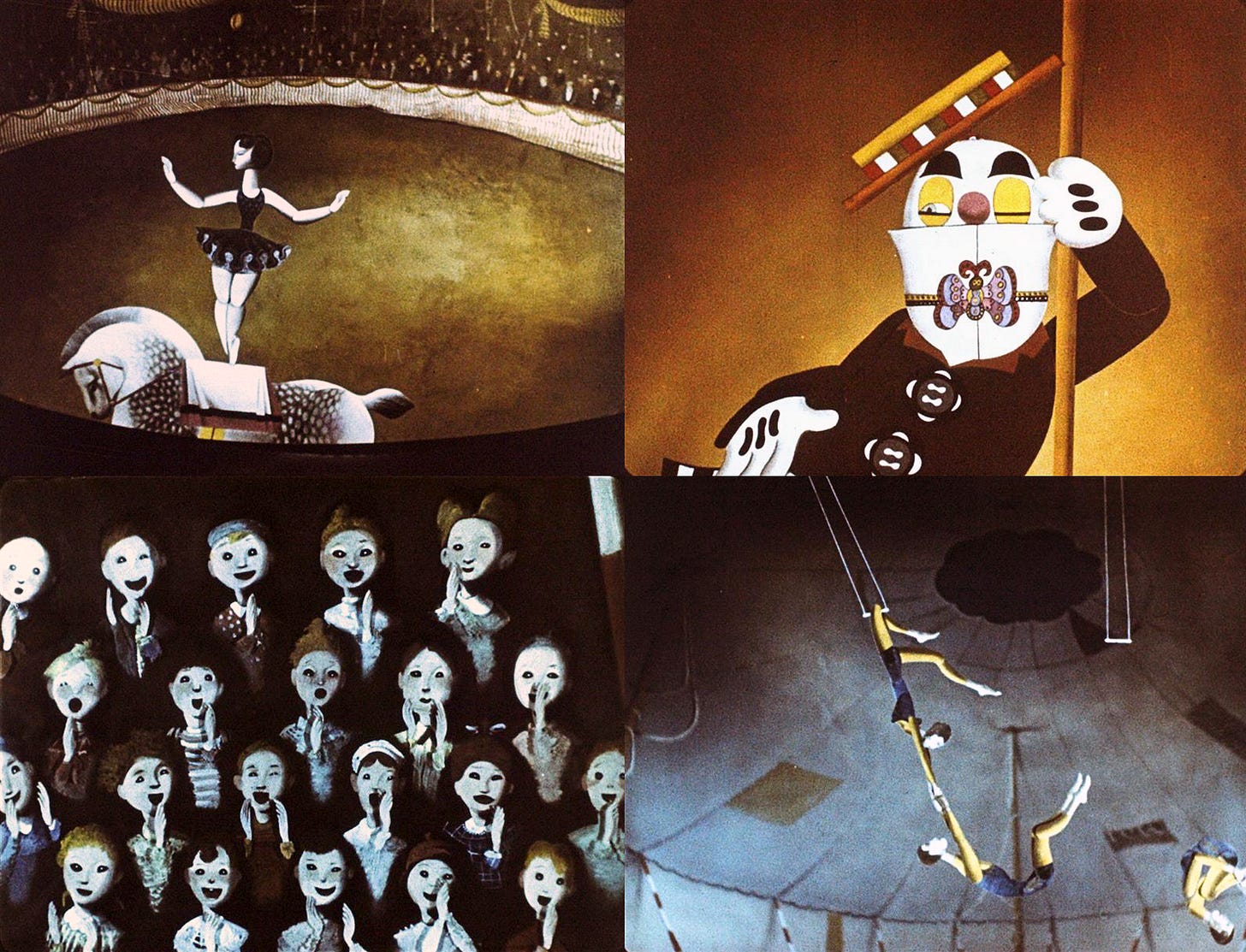

In the interview, Látal related his early experience with cutouts on Trnka’s Merry Circus (1951), a plotless but mesmerizing piece whose “sole purpose was to amuse and surprise the audience.”1 Látal was one of its few animators.

Trnka made The Merry Circus partly, according to Látal, because he was drawn to the idea that cutout animation could preserve the designer’s intent. Trnka didn’t animate — and he believed that cel animation involved “too many middlemen” who “weakened the originality of the artist’s drawings,” per one historian. As Látal pointed out, cutout characters are those original drawings:

Compared to cartoons this is a significant advantage, as the artist’s hand is preserved, down to partial shadows and subtle color gradients. That was definitely one of the reasons why Trnka started filming The Merry Circus. He knew that no one would redraw his figures, that they would remain really Trnka’s.

Alongside his own section of the film, Trnka brought in three Czech painters and illustrators from outside the animation world to craft cutouts with him. “Each of them had a completely different style and each had to design one circus performance for the film,” Látal noted.

Done right, cutouts bring that kind of uniqueness to animation. There’s a special power to them, a richness of artistry. Trnka returned to them several times after The Merry Circus, but he was far from the first artist to recognize what they can do.

Years before Trnka, Germany’s Lotte Reiniger had used cutout silhouettes to infuse a deep design sophistication into films like The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). She helped to pioneer this style of film, and was dedicated to it throughout her life — influencing animators around the world.

But even Reiniger was tapping into something older and more elemental. Her main influence was the shadow play, where live puppeteers manipulate cutouts behind a screen. These plays existed in Germany, but, as Reiniger wrote, “Learned books about shadow-plays agree that the art originated in China.”2 They’re still performed by certain troupes in China — with magical results.

The shadow play is an ancient form, and a precursor to animation itself. It predates “traditional 2D animation” by thousands of years. This is the base underpinning cutout animation, from the intricate design to the jointed quality of the motion. Just as Trnka’s puppet films gain part of their power from their roots in Czech puppet theater, the power of cutout animation comes partly from this history.

It’s something that China’s own animators knew when they made their first full “paper-cutting” animation, Pigsy Eats Watermelon (1958), at Shanghai Animation Film Studio. As the company’s artist Pu Yong later wrote, “The birth of paper-cutting film was influenced by shadow-puppet plays.”3

Like ink-wash animation and paper-folding animation, Chinese cutout films were intended to express tradition. They combined shadow plays with folk papercraft. There was a dose of modern thought, too — as the artists developed these forms in new ways for animation.

Take the discovery of a special hinge for the characters’ joints. Reiniger had used fuse wire for this, but the Shanghai artists found another way, according to Pu Yong:

Our old masters explained [the process] to me: “You need to first roll out the sticky side of the medical rubber tape. Then, you have to cut all this rolled-out tape into small granules using scissors. Once you have got all these small granules, you place them between two sheets of paper. Right in the middle, the paper will be able to move.”

The Shanghai artists also learned a new trick for cutting paper. Alongside the usual sharp-edged cutouts, Pu talked about “picking” — subtly ripping the paper’s edges, so that “the contour lines of [a] character would appear misty, which made it integrate wholly into the colors and artistic conception of the background.”

Pu called The Fight Between the Snipe and the Clam (1983) the “peak of paper-cutting animation and picking.” It looks like an ink-wash film, but it isn’t one. Instead, it creates a similar effect through the rich possibilities of cutout animation — bringing the designers’ vision, and ancient tradition, directly to the camera. And with wildly different results than Trnka’s Merry Circus.

For Pu Yong, like Trnka and Látal, cutout animation was a powerful form. Yet Pu also saw it as an imperfect one. “The disadvantages of paper-cutting films are spatial limitation and the lack of a sense of depth,” he wrote. “This is paper-cutting’s fatal flaw.”

It’s a quirk inherited from shadow plays, which exist on a flat plane by nature. That’s the default for cutout animation as well. Still, just as the Shanghai artists developed tradition to make their films, at least one set of animators elsewhere in the world found a way around this “fatal flaw” of flatness.

That was the husband-and-wife team Yuri Norstein and Francheska Yarbusova in the USSR.

Even as a young animator on other people’s films, Norstein was already bringing new ideas to cutout animation in the ‘60s. At Soyuzmultfilm, he shocked the team behind Lefty (1964) with his unusual methods. As author Clare Kitson explained:

… [the] characters were made with beautifully engineered hinges holding the bodies together while allowing adequate movement at the joints. With a mixture of amusement and terror the crew one day observed Norstein tearing the hinges off all the cutouts. His hunch that these hinges were impeding the free and natural movement of the characters turned out to be absolutely correct and was later vindicated in his own work as a director.4

Soviet cutout animation was nothing new — it had existed at least since the ‘20s. But Norstein and Yarbusova, once she started collaborating with him on The Battle of Kerzhenets (1971), turned this style into something else.

Shadow plays are flat, but Norstein and Yarbusova’s films grew into a study of layers. By the time of The Heron and the Crane (1974), they were using stacks of “cut-out cel with gray paper stuck underneath and texturing on top” to render Greek columns, wrote Kitson. For Norstein, it recreated the way that classical Western painters like Rembrandt had layered paint. Even the characters in these films are layers.

And these layers weren’t always placed on a single plane. In films like Hedgehog in the Fog, they were often spaced apart on stacked sheets of glass, shot through Norstein’s multiplane camera setup. It’s a system that creates films “structured at the same time in three dimensions and in two dimensions,” according to writer Mikhail Iampolski.

Here’s Norstein on the process of layering:

The house in Tale of Tales, for example, is made of about ten layers. There’s the house, then more layers of cel with texture on them. And then you draw a few details on the last one. Then the layers play off each other and you get an element of improvisation that’s full of creative energy […] even the thickness of the backgrounds plays its part. […] If you painted the same thing on a flat surface you wouldn’t get the same optical effect. And also, when we get a complex background and then a texture one level above it [on the multiplane animation stand], then you get a play of the air, of the space. I love that, and Francheska does it perfectly.

Yarbusova is especially important to highlight because it’s her art that we see in films like Hedgehog in the Fog and Tale of Tales. Just as Trnka and his co-designers saw their characters and world appear under the camera in The Merry Circus, Yarbusova offered the same to Norstein’s most famous work. She made the art, and he made it move.

Together, Norstein and Yarbusova created a kind of cutout animation that, even more than the Shanghai Animation films, has one foot firmly in the modern. While shadow plays are there at the root, the techniques that this husband-and-wife team took from dioramas and experimental filmmaking might be even more crucial to the final look.

But cutout animation can do that. It has an odd power to adapt — to take on whatever form best expresses the artists’ vision. Animators around the world have brought their own ideas and reference points to it, and it changes wildly each time.

Whether it’s the modernist illustrations that Trnka and his team used in The Merry Circus, or the expressionist dreamscapes of Reiniger, or the traditional ink-wash style in The Snipe and the Clam, or even the indefinable work of Norstein and Yarbusova, cutout animation has a way of putting “the artist’s hand” on the screen.

There’s a power to cutout animation — and a scope as wide as the artist’s imagination.

Thanks for reading! We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s issue.

Like we mentioned at the start, we’re really excited to explore Animation and Time further. More and more, our research library is deepening our ability to study animation from around the world.

For us, this newsletter is a research project as much as it is anything else. We love learning — and sharing these discoveries with you all. We can’t wait to see what the future holds as our library continues to grow.

See you again soon!

From the book Jiří Trnka: Artist & Puppet Master, written by Jaroslav Boček.

From Lotte Reiniger’s book Shadow Puppets, Shadow Theaters and Shadow Films, which is available to borrow on the Internet Archive.

Pu Yong’s words across this issue come from Chinese Animation and Socialism — quickly becoming one of our most-cited books.

The details about Norstein and Yarbusova’s process are all from Yuri Norstein and Tale of Tales: An Animator’s Journey by Clare Kitson.

A delicious article. It's been very useful for me in exploring the styles and techniques for my own and I keep coming back to it for reference.

Fascinating read! Had no idea. Thank you for writing on this! I find it so dang interesting! My girlfriend and I saw a BBC video that documented a Chinese puppeteer group, and a lot of this art history blew my mind. Shadows and puppets were like the first blockbusters to hit the ancient world streets lol. That in itself sounds like a rich starting point for a fiction! Have a great weekend. Amazing article. - Dar