Happy Sunday! The Animation Obsessive newsletter returns with a new issue — and this is the agenda today:

1️⃣ What we wrote in May.

2️⃣ Global animation news, and Sasha Svirsky’s Master of the Swamps.

New here? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, right in your inbox:

Now, let’s go!

1: Looking back on a month

As we write this, May isn’t quite over yet — it’s the 28th. But publishing a twice-weekly newsletter puts you on a weird calendar. This is our last newsletter day of May: the next one isn’t until June 1. In a sense, the month is already over for us.

Two-plus years into the Animation Obsessive newsletter, our team is still small: one main writer, one art director and news researcher, one reviewer and sounding board. It’s hard to publish on time with just three people, but the upside is we’re flexible — and we get to do what we want. We follow our shared interests and hope that readers will be interested, too. As we go deeper into this medium, we stay excited ourselves, and we suspect that others won’t be bored if we aren’t.

And, looking over our issues from May, we can safely say that we’re still going deeper.

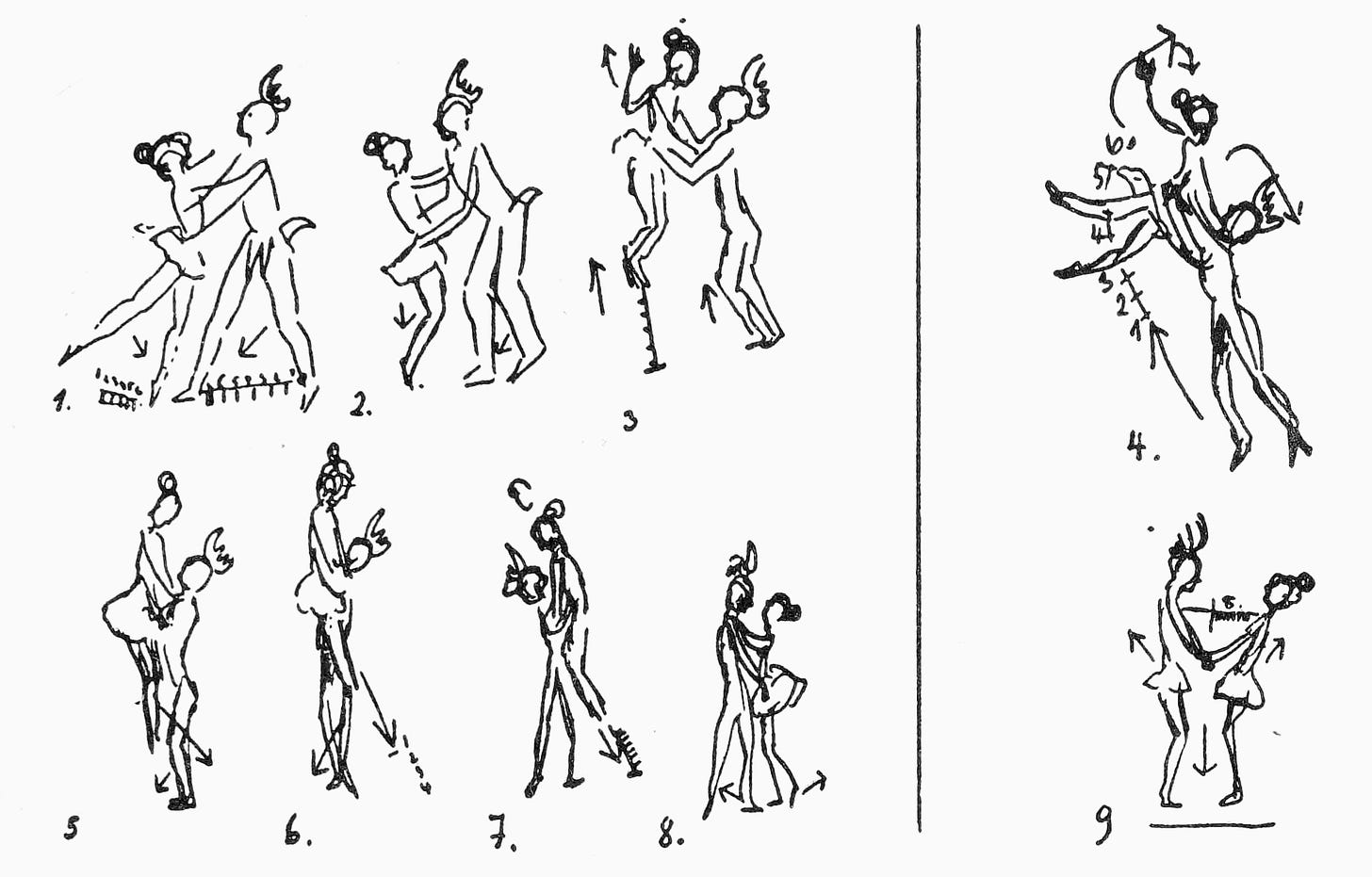

We started the month with a first for us: a study of Lotte Reiniger’s animation technique (for members). Born in Germany in 1899, Reiniger is one of the early and all-time animation greats. We’ve admired her silhouette films from afar for years — but she felt like too big of a subject to cover well, like trying to write an article about Snow White or My Neighbor Totoro. We’re glad that we got over that mental block.

Reiniger wasn’t just a pioneer — she was a master stop-motion animator, with a real talent for conveying character. She had an eye (and a memory) for movement, which she drew from life. Here’s a quote of Reiniger’s we ran across in our research:

I remember well, when I was studying at the zoo, how people looked at me astounded when I tried to imitate the animal’s movements in front of the cage, trying to memorize its timing, and how my husband burst out laughing when he discovered me crawling on all fours on the floor at home, to get the feeling of the animal’s movement into my own bones. [...] You must not copy a naturalistic movement, but must feel the movement within yourself, for when you will have to animate an animal you must be that animal, moving as it does. The animation will always be stylized, but this stylization must be true.

In many ways, Reiniger was a realist, despite the unrealistic veneer of her films. She felt that her silhouette technique worked best when the characters moved “with the utmost faith to life, so that one totally loses the sensation that there aren’t any true actors [on the screen].”

Reiniger didn’t use the cartoon motion perfected by studios like Disney or UPA. It was something else. This month, we found ourselves publishing a few articles about this kind of animated realism. We followed the Reiniger piece with one about the anime film Run, Melos! (1992), which also embraces realism — with totally different results.

The Melos write-up is a revised reprint of an issue from last year, but we were very happy to revisit it. Not much has been written about this film in any language, and we loved the chance to bring it to more people. Melos uses the stylized realism that anime can claim as its own development. Its director said, “We still can’t compare to Disney at fantasy, but Japanese realism anime far exceeds the world standard.”

His comment put us in mind of a great quote from Christian Desmares, the co-director of the French film April and the Extraordinary World (2015). For that project, the team had to set the comic art of Jacques Tardi in motion, and anime realism showed them how to do it. Here’s Desmares:

How do we make a Tardi drawing move? [It] isn’t obvious, as there are many ways to make a drawing move. There’s the Disney style, an elastic animation with deformations, or a more rigid and realistic style, like the Japanese, among others. I chose to lean more towards the Japanese style, which enabled me to not distort Tardi’s drawings too much. Of course, we had a little fun, since this is part of animation, but we didn’t perform large distortions which could denaturalize Tardi’s drawings. I was influenced by the Miyazaki universe [...] So I found a type of coherence between the way I made the characters move and a similar style used in Miyazaki films like Porco Rosso, Totoro, Princess Mononoke, for example.1

We had a third brush with animated realism in our piece about The Cow (1989), a Soviet film painted on glass. We’d wanted to cover it for a year or more and finally had the chance. It approaches realism differently than either Reiniger or Melos, and it reveals clearly that animated realism isn’t just one thing.

Director-animator Alexander Petrov took from Rembrandt for The Cow, but not only him. As a painter, Petrov has acknowledged his love for Socialist Realism: the much-derided official Soviet style. “My teachers were realist painters,” he said in 2008, “who created things perceived today with a fair amount of irony and cynicism. Nevertheless, they created it sincerely. They were seeking harmony in painting.”2

The Cow is an oil painting in motion. Its realism is often an impressionistic one, but it’s still realism, and it has a powerful effect — which Petrov accented with his skill at painting realistic movement; not just images. We learned that director Fyodor Khitruk, who was Petrov’s animation teacher and an artistic supervisor on The Cow, had a hard time believing the film wasn’t rotoscoped.

Realism didn’t occupy us all month, though. Our most recent issue, from Thursday, dives deep into the art of two-drawing animation — one of the least realistic types of cartooning there is. It has way more energy and complexity than most realize.

One example we looked at was Fyodor Khitruk’s debut film: The Story of a Crime (1962), which reduces many actions to just two poses. The short helped to spark a revolution against Socialist Realism in cartoons, a move toward mid-century modern graphics and “limited animation.” We were surprised to learn that Khitruk attributed his switch to the influence of Czech animation — rather than UPA or Zagreb Film.

Even so, UPA mastered two-drawing animation first. See Fred Crippen, the hyper-minimalist animator who had a key part in UPA’s experimental series The Boing-Boing Show (1956–1958). “He could animate a person walking or playing the piano with a two-drawing cycle,” noted the book Cartoon Modern. “Take away one drawing and the scene would be completely still. His style of animation was so unconventional that it confused many of the studio’s veteran animators.”

Going through a series of two-drawing cycles can make for boring animation — but not in Crippen’s case. Cartoon Modern argues that “there is nothing formulaic or standard about the movement; every action has its own unique graphic solution.” The same is true for the other cartoons we explored in the piece, from Czechoslovakia to Yugoslavia to Kid Cosmic to Bigtop Burger.

Anti-realistic animation also came up when we wrote about three Hungarian films we love (another issue for members). Although part of the Eastern Bloc, Hungary fostered one of the most arthouse animation scenes of the 20th century — as seen in Son of the White Mare. It made room for rulebreakers.

One of them was Sándor Reisenbüchler (1935–2004), whose film The Kidnapping of the Sun and Moon (1968) was among the three we covered. It’s a gorgeous, intense piece. Reisenbüchler was a creative rebel who often worked from home, rather than in Hungary’s official animation workshops. He made films mostly alone and noted in the ‘70s that he used neither storyboard drawings nor exposure sheets.

Here’s what he said about The Kidnapping of the Sun and Moon:

I made this film on a stool. I lived in the countryside, 30 km from Pest, in Felsőgöd, in dire poverty. […] My son was born just then, and my wife joined in between breastfeeding to fill in the dragon with a grease pencil. It’s actually a family short film. […] I had never been abroad before. With this film, I became popular all over the world. This shows that one can make a film on a kitchen table and a credenza.

All that said, we don’t go into a month of the newsletter with a theme in mind. Even in May, a couple of issues had little to do with realism or anti-realism. These were the one about Chicken Run and the one about Munro, the first foreign-made cartoon to win the Oscar. Both of them were long-term goals for us.

The Chicken Run piece, on Aardman’s fight to keep its quirky identity while making a feature film (with Hollywood money), is the first public issue of our newsletter about Aardman. We love the studio’s work and wrote about Creature Comforts earlier this year — but that was for members. This will be, with luck, one of many more public issues on Britain’s best stop-motion team.

As for Munro, it’s been considered since the first days of our newsletter, back in early 2021. It’s a complicated story — how an Oscar-winning cartoon was outsourced in secret to a country behind the Iron Curtain — and we weren’t sure how to approach it. Our research for recent articles like America’s Outsourcing Machine opened the way.

And that wraps up our May 2023. We’re working on a lot more for June, but we’ll keep our next issues under wraps for now, just in case plans change. For us, articles often fall through and get replaced on short notice. Doing this newsletter has always meant adapting, making things work.

It can be hectic — but we don’t get bored.

2: Animation news worldwide

Sasha Svirsky and Great Russian Villains

Over the last couple of weeks, a Russian animated series has been drawing attention — and stirring controversy. It’s called Great Russian Villains, and it questions the heroism of Russia’s past national icons. That includes people known worldwide, like Vladimir Lenin, and some mainly famous inside Russia (see: Alexander Suvorov).

The point is to undermine Russia’s myths — the ones propping up the war in Ukraine. This outrages propagandists like Yuri Kot, a pro-Kremlin journalist who once floated a nuclear attack on America. Kot is calling Great Russian Villains a “denigration of great Russian people” perpetrated by “Russophobes,” and a reason to outlaw “Russophobia.”

This YouTube series isn’t just about shock, though — real artistry and backing went into it. The animators are mostly anonymous, but this week’s episode The Master of the Swamps is an exception. It comes from artist Sasha Svirsky and his wife and collaborator Nadya Svirskaia. Their warped, saturated collage films (Vadim on a Walk, My Galactic Twin Galaction) have gotten serious notice at home and abroad. We’re fans.

Svirsky’s work is often political, and he’s vocally opposed to the war: he signed an open letter against the invasion in February 2022, and he and his wife reportedly left Russia for Berlin in short order. The Master of the Swamps is a harrowing reevualation of history, done with all the bright, lo-fi visual chaos that’s wowed us in films like Vadim. Svirsky provides the deadpan narration.

Over the weekend, we reached out to Svirsky to ask about his episode. He told us:

The film is devoted to Russian emperor Peter the Great, who lived in the late 17th and 18th centuries and brutally westernized the country. He aspired to build a great empire and considered this goal worth paying any price. Centuries have passed since his reign, but the latest events show us that his bloody dream still contaminates people’s minds in Russia.

The weird heritage of the distant past is haunting us as a shitty horror under its familiar mythologized disguise. And glorious pictures of glorious historical figures encourage modern cosplayers to bring this horror into our present.

Svirsky further explained the roots of the Great Russian Villains project — the concept, and how it came together. As he told us:

It consists of 10 short films made by different animators in different styles. All directors have Russian roots.

The idea of producers Ilya Khrzhanovsky (film director) and Mikhail Zygar (journalist, historian) is to attack the widespread way to represent Russian history as a glorified past, where all rulers just work on making Russia bigger. And now Russian propaganda often refers to that “great” past and justifies wars as a way to make Russia stronger.3

The series is ongoing — The Master of the Swamps is its sixth installment. You can find the whole playlist here, or watch Svirsky’s episode with English subtitles below:

Newsbits

The hype for the American film Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is reaching a fever pitch. Early reactions are glowing, and Boxoffice Pro projects a minimum of $95 million in revenue for its three-day domestic opening. It hits theaters June 2.

New details about the Japanese film The Mourning Children by director Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World). There’s now a small teaser with music, and behind-the-scenes footage with pencil tests. Set in the Heian period, the project is powered by research: Katabuchi started planning it back in 2017.

The Russian studio Soyuzmultfilm has a new YouTube channel to host auteur animation it’s produced in the 2010s and 2020s.

Meanwhile, Russian animation scholar Pavel Shvedov put together a top-hundred list of domestic auteur animation made in the past decade, with links to watch. A few include Warm Star by Anna Kuzina, BoxBallet by Anton Dyakov and Dacha, Aliens, Cucumbers by Katya Mikheeva.

In Ireland, Cartoon Saloon has a trailer for its feature-length Puffin Rock movie. It debuts in Ireland on July 14.

At Annecy, five TV pitches from Ukraine will seek international partners at the “Animation in Ukraine Now!” event. Among them are a show based on Mavka and the very cute Darling Zhu: Garden’s Tales by Anatoliy Lavrenishyn (Viktor_Robot).

America’s other big story: the Writers Strike, which primarily targets live-action film and TV but does cross over with animation. On Tuesday, over 200 members of The Animation Guild reportedly joined the picket line (watch).

The web of co-productions between Japan and Europe grows, as Toei partners with Studio La Cachette of France for the new series Le Collège Noir.

Suzume became the biggest anime film (and biggest Japanese film) ever to hit Indian theaters, with a take above ₹10 crore.

In Japan, the exhibition “Cityscapes in Anime Background Art” opens June 16 and will continue into November. It showcases backgrounds from Akira and more. The event’s hosted by the Kanazawa Museum of Architecture, and it’s curated in part by Stefan Riekeles, author of the eye-popping artbook Anime Architecture.

Until next time!

From an interview with Foma.

Ilya Khrzhanovsky is the son of animation director Andrei Khrzhanovsky, whose dissident film Glass Harmonica (1968) was banned in the USSR. We wrote about that incident back in March. Andrei Khrzhanovsky is still alive — he’s now in his 80s, and a fellow opponent of the war in Ukraine. According to his son, he’s permanently left Russia in protest.

My new favorite newsletter. ❤️

Great post, such good detail.The animation of the Boing Boing show looks great to me, simple and effective. Really like how you’ve broken down the drawings, excellent. Thanks as ever for a great piece 😎