Happy Sunday! We’re here with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Today’s lineup goes like this:

1) A brief history of outsourced American animation.

2) Animation newsbits.

Before we start — animator Darcy Woodbridge shared a very cool animation test he made using Moho. He gave his work a richly painted look that bounces and stretches with the character, but the effect was created with vectors, rigs and tweening. Moho itself shared a behind-the-scenes video to show how it was done.

With that, here we go!

1 – American money

Animation outsourcing has made headlines lately. There’s word that parts of Invincible were secretly produced in North Korea. Meanwhile, DreamWorks is moving jobs to “lower-cost geographies” to save money. The list goes on.

This trend may be in the news, but it has a history. A murky, complicated one. In American TV animation, most shows conceptualized stateside get outsourced to animation studios elsewhere. That’s been the norm for a long, long time.

In fact, the American project of outsourced animation began in earnest back in the late 1950s. And no one person invented it — across the film and TV industries, the idea was in the air.

It came to animation by way of the live-action world. So-called “runaway productions” — film and TV made abroad, on the cheap — were already controversial. “These producers pocket the difference between American union scales and slave wages,” argued a Hollywood union council in 1959, “and then take advantage of a loophole in the law to mask this foreign-made product as American.”1

Shooting a film in Europe or Asia was easier than animating abroad, but some Americans were determined to reap the benefits. By 1958, runaway cartoons were the “hot topic of discussion in animation circles,” according to historian Keith Scott.

Why? Animation was expensive to make, especially in the booming TV business. Here’s the view of one producer from 1961, as summarized by Broadcasting magazine:

The demands of television for program material are so great and the price the medium is willing to pay for programs so small that it’s impossible for a conscientious cartoon producer to turn out the footage that is called for without sacrificing either quality or solvency.

Many saw outsourced cartoons, which dodged American unions by going to countries whose currencies were weak against the dollar, as the answer. But were they?

Rocky and Bullwinkle by Jay Ward Productions was the first major cartoon to leave the states. Len Key, a businessman with the studio, hatched a scheme: they would animate the series in Japan, for peanuts.

His proposal was a bit shady, but so were Key’s business contacts in Japan, who played him even as he tried to play them. He discovered when he went to Tokyo in late 1958, “The so-called animation studio didn’t exist. There were just chalk marks on a vacant lot. They’d intended to finance the building with our show contract.” Japan was out.

So, Key took the project to Mexico City. A wealthy contractor there, who already had a local animation studio of his own, agreed to work with Jay Ward Productions and General Mills. “It was put together in a fairly sleazy fashion,” recalled Bill Scott, head writer for Rocky and Bullwinkle. Smuggling and corruption were critical to it, as the Americans funneled studio materials into Mexico and dodged workplace inspectors.

Even as Rocky and Bullwinkle premiered on American TV in 1959, the Mexico City studio was in shambles, and the American supervisors were battling their underpaid Mexican team. For a while, it was a historic disaster. Yet the show was a solid success.

We’ve told this story before. On Rocky and Bullwinkle, the “below-the-line” workers in Mexico went uncredited, and their conditions were often shocking. Things did improve a bit — and the studio, renamed Gamma Productions in the early ‘60s, became a major outsourcing destination for shows like Underdog.

Problems remained, though. “The quality of the animation was very limited,” recalled Gamma animator Daniel Burgos. “The films came pre-directed, the movements were very indicated and there was no good supervision.” The pay wasn’t great, either.2 It wasn’t especially satisfying work, but many of the shows were hits in America.

There seemed to be potential in questionable animation deals like these. Len Key wasn’t the only American businessman who saw it. Far away, in Eastern Europe, a producer named William L. Snyder was setting up shop in communist Czechoslovakia. Despite the Iron Curtain, despite the Cold War and the nuclear arms race, he started outsourcing films to a Prague animation team in the late ‘50s.

Snyder was “among the first Americans to do business in postwar Eastern Europe,” according to The New York Times.3 He was from New York himself, but he went back and forth to Prague. How did he deal with the communist officials? “He was a smooth talker; it turned out that all he needed to do was offer Western cash and all doors were opened.”

Snyder cut the deals necessary to establish his own unit at the state-run Krátký Film studio in Prague. Krátký Film also housed Jiří Trnka, who was making A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1959). Snyder’s plan was to use this new unit to do high-quality cartoons for very little money — maybe $5,000 per film. To the Czechs, even a little was a lot.

One of the few at the studio who knew any English was animator Zdeňka Najmanová, and she didn’t know much. “But that’s why the director called me when Snyder came to the studio for the first time,” she remembered. “He said, ‘Zdenka, you have to guide him through the studio and show him everything. We have nobody else to do it.’ ” Eventually, Snyder pressured Krátký Film to make her his production manager.4

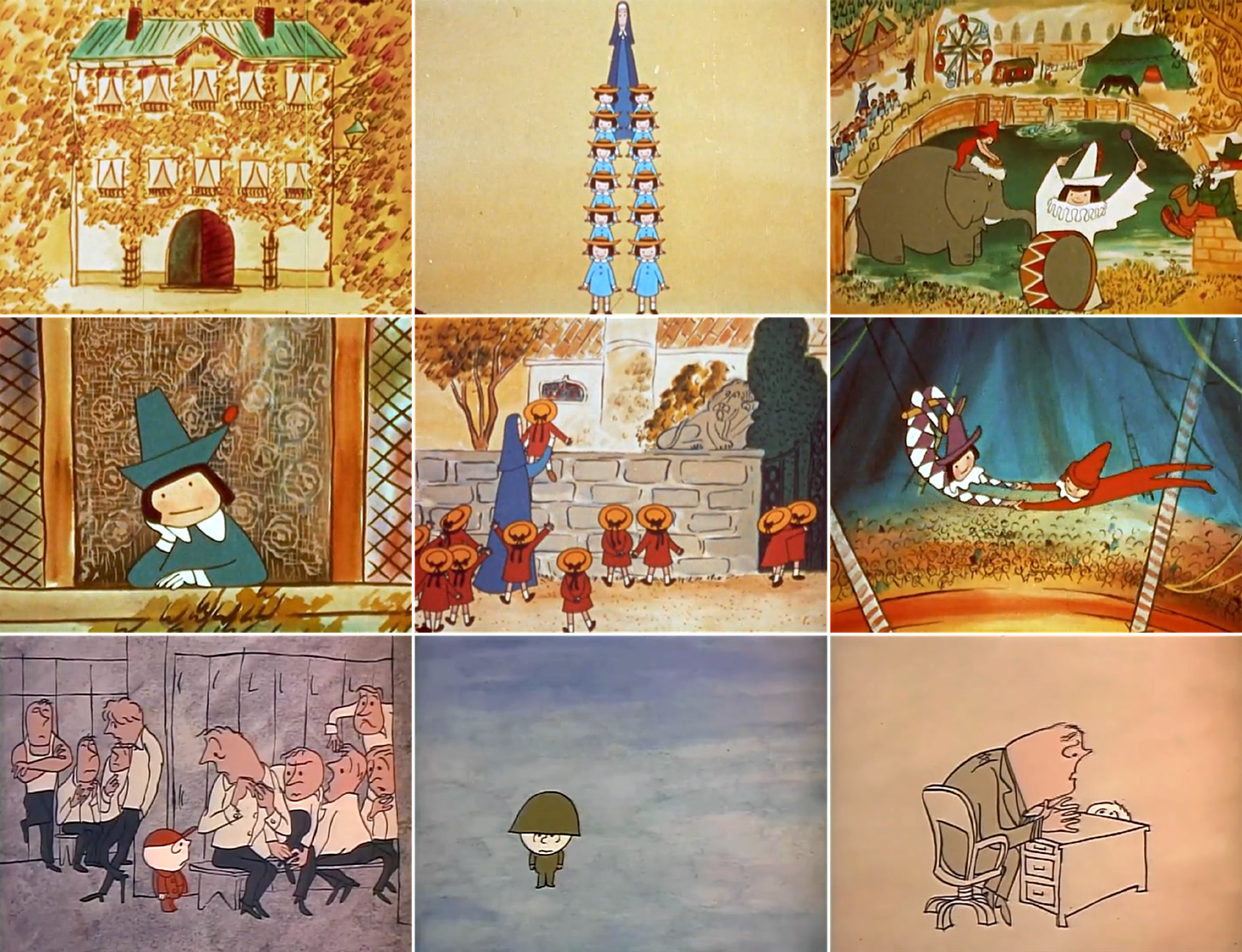

To create cartoons for the American market, Snyder bought the film rights to several Madeline books. As director Václav Bedřich recalled, many years later:

... a certain Mr. Snyder was active in Prague, and for him we made the Madelines, which were very nice films. Snyder showed us the very first film from this series, which was made by Stephen Bosustow [of UPA] ... In addition, Snyder also brought books by Ludwig Bemelmans, the author of the original series, which also contained his original, pastel color illustrations. They were very nice books — and we made about five short films based on them.5

Bedřich directed at least three Madelines, but the connection to the Eastern Bloc was hidden from the public. It was dangerous. The Krátký Film studio didn’t appear in the credits — only Rembrandt Films, Snyder’s New York production company. Bedřich was credited variously as “V. Bedrick” and “V. Bedrik.” Zdeňka Najmanová’s name was even more Americanized: “S. Nauman.”

Despite their American veneer, though, Snyder saw the films as too foreign. He’d shown UPA’s original Madeline cartoon to the Czechs as reference, but pieces like Madeline’s Rescue (1959) and Madeline and the Bad Hat (1959) came out looking and feeling European.6

And so he hired Gene Deitch, an animation producer in New York, to supervise the Prague team. Deitch wasn’t sure about the deal at first. He later described Snyder as a fast-talking, cigar-chomping salesman who was “constantly hacking and spitting.” Someone who wore striped seersucker suits and made wild, improbable claims. But Deitch gave in and went to Prague in October 1959.

Ahead of Deitch’s arrival, Snyder sent a letter to the Czechs. “He wrote that he is sending to Prague a young, talented, one of the best directors. [...] And I got furious,” Najmanová said. “Why do they send me from America someone who will put a nose into our filmmaking?”

These tensions relaxed. Although Deitch found the animation facilities hopelessly out of date, he and the Czechs managed to make Munro (1960). It won the Oscar in 1961.

Once again, though, the Czech involvement was concealed. Snyder took credit for the film, and the Oscar went to him. As he told the papers in 1961, “Why, we thought Munro would appeal only to the sophisticated — not that it would be a hit with the dear little old ladies from Iowa. But it is.”7

Snyder and Jay Ward Productions operated on opposite sides of America, and they outsourced to totally different places. Gamma Productions in many ways resembled a sweatshop. Krátký Film was a place for artists to make art. But one studio won an Oscar, and the other made one of the most beloved TV cartoons of all time.

What united it all was the power and draw of American money: producers who had it, and the people who wanted it. Yet it was still up in the air how much cheaper it really was to animate in foreign countries. Outsourcing had been based on a theory, which was now being tested by reality.

Deitch once wrote that, when his crew was put in charge of Tom and Jerry in the early ‘60s, each film cost maybe a fourth as much as an American cartoon. The math wasn’t always that straightforward. Here’s a newspaper report about Gamma Productions from 1964:

Customs duties and the time-consuming red tape involved in doing business south of the border virtually wipe out these advantages or any tax gain that might accrue from a venture in a foreign country.8

True or not, Gamma claimed to pay its Mexican staff better than the local competition: “up to 100 pesos ($8) a day, far more than other youngsters of their age usually earn in Mexico.” Likewise, Snyder’s money was no joke in Czechoslovakia. As his emissary, Deitch was valuable enough to receive privileges unknown to anyone around him. He could come and go as he pleased:

I was the only person in the East Bloc, I heard later, that had what was called ... [an] unlimited return visa. I would get this for a period of six months at a time. I didn’t have to say anything to anybody.

Around the world, American money opened doors. It was a truth that producer Arthur Rankin leveraged in Japan right around this same time.

During the ‘50s, Rankin came into contact with the stop-motion films of Tadahito Mochinaga, a Japanese animator. As we’ve written, their partnership would lead to Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964). But, before Rudolph, there was a series called The New Adventures of Pinocchio (1961).9 And it’s just as important to our story today.

Tadahito Mochinaga was a veteran animator working at a new studio — MOM Productions, which he’d co-founded in Tokyo in 1960. It made stop-motion commercials. Mochinaga’s goal was to earn money from advertisers to support his own, independent films. He wasn’t interested in Rankin’s pitch, and resisted it.

The New Adventures of Pinocchio was a big job: around 130 episodes, each one five minutes long. The Americans wrote and conceptualized them, but it would be up to Mochinaga’s team to animate them at a rate of 750 seconds per week.10 Pinocchio’s budget was large enough to support Mochinaga’s team for a year, but it would also take a year.

According to historian Jonathan Clements, the series:

… was sure to occupy the entire labor force of his company, leaving no space on the schedules for any of the advertising clients whose work had largely funded his previous entertainment films. Essentially, the Pinocchio contract would occupy Mochinaga and his staff for an entire year, in which time they would be entirely reliant on Videocraft’s money.

Mochinaga accepted Pinocchio only grudgingly — his studio needed the funds. He didn’t enjoy it, and later wrote that “the shooting in the studio was fierce and punishing every day.” His hope was to make one project for the Americans and be done with them, but events (deepening debt, a massive fire) aligned to keep him working with Arthur Rankin and Videocraft.

The problem wasn’t that the projects were underfunded. Mochinaga and his studio received lavish budgets for shows like Rudolph. It wasn’t the difficulty of the work, either: “fierce and punishing” were good words for Japan’s local animation industry, too. Mochinaga’s real concerns went deeper. Here’s historian Daisy Yan Du:

When [Mochinaga] visited China in October 1978, he warned Chinese animators interested in taking projects outsourced from abroad by listing the disadvantages he had experienced. First, working on outsourced projects cut off the animator’s and studio’s ties with Japanese children. Second, because the profits from outsourced projects tripled [those of] creative work, animators’ salaries working for outsourced projects were much higher than those working on creative animated films, putting tremendous financial pressure on domestic creative animated filmmaking. Third, working on projects outsourced from America led Japanese animators to imitate American gags and styles. Fourth, no matter how hardworking local animators were and no matter how wonderful outsourced films might look, domestic audiences could not watch them.11

Unlike with Len Key and (arguably) Snyder, it’s hard to call Arthur Rankin an opportunist. Mochinaga’s studio wasn’t being exploited. Yet the work wasn’t strictly creative, either — the animators were executing American ideas. And the power of American money was so great that it distorted the industry around them.

Mochinaga’s 1978 argument went ignored in China. Mao was dead, and the country was opening up to foreign business for the first time in decades. Even so, his warnings proved to be prophetic.

Back then, Shanghai Animation Film Studio was the seat of Chinese cartoons — responsible for many of the greatest animated films of all time, like Three Monks (1980) and The Buffalo Boy and His Flute (1963). It specialized in animating traditional Chinese crafts. Shanghai artists borrowed from ink-wash paintings, paper-folding, shadow plays and more. Hundreds of people worked at the studio.

As the ‘80s wore on, though, foreign studios began to pop up in China. They offered the chance to work on TV cartoons for the Americans. While Shanghai Animation was state-funded, it paid next to nothing compared to the capitalist outsourcing studios.12

This competition gradually brought about a crisis. Zhou Keqin, who served for years as the president of Shanghai Animation, described the late ‘80s as a breaking point. He’d been out of the country for an animation event in Brazil. As he remembered:

Once the Brazil festival had ended, I returned to Shanghai. On my first day back to work at the studio, I was greeted by a scene of desolation. A staff member came to me, saying, “Mr. Zhou, you’re back! Everyone in the studio has left.” I was alarmed and quickly investigated the matter … a large group of animation talents left without saying goodbye, hopping to international or foreign animation companies in Guangzhou and Shenzhen in the south of China … tempted by the high salaries those companies offered.13

He characterized it as “severe brain drain,” claiming nearly 100 employees in short order. Shanghai Animation itself took outsourcing work for money during this time. It continued to make artistic films where it could, but it got harder.

Animation in China was entering a downward spiral — caused not by poverty, but by money. Here’s animator Zou Qin, who created the artistic short Deer and Bull at Shanghai Animation, speaking in 1993:

When I started working in the studio, everybody liked to devote their lives to animation, to do the best work they could for China. Since 1986, with the “open door,” everyone has come only to think how best to make as much money as they could on their own. I worked a whole year to make Deer and Bull and made only 800 yuan [$125 at the time] above my regular salary to do this. When I worked for Pacific Rim Studio in the South, I made 5,000 yuan a month doing very simple work that required no intelligence. That was several years ago [in 1990]. Now I could make 8,000 to 10,000 yuan per month working for a foreign animation producer.14

Zou wasn’t happy about this setup — he felt that Chinese animators had lost their way, “copying the West” and forgetting how to do thoughtful animation of their own. But the appeal of a place like Pacific Rim was real, despite the lack of skill and creativity involved. Founded in 1988, the studio employed over 400 Chinese workers by 1990. They contributed to Disney’s TaleSpin, among many others. The job was robotic, but it paid, and that drew people.

These assembly-line animation jobs were increasingly available during the ‘80s and ‘90s — not just in China, but in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. American cartoon work was easy to get. Whether it truly cost American companies less than domestic production was still a difficult question, though. Sometimes it did. But not always.

In 1987, when the animation for DuckTales was being outsourced to Japan, a Disney executive said this about the project:

It is not cheaper for us to do it over there. But they have a talent pool of fantastic draftsmen that we don’t. We have some talented artists over here, but nowhere near enough to handle the massive amounts of footage we need. And the work ethic in Japan is phenomenal: they all work six-day weeks, and probably at least 10-hour days. Some of them work all night. I’ve gone into the studio in the morning and seen guys sleeping under their desks — it’s unbelievable.

For artists outside America, these outsourcing jobs were both a draw and a threat. They paid, but they could sometimes hollow out local animation: brain drain in the sense that artists pulled back from creative projects, and in the sense that ability declined over time. Like at Gamma, the decisions were made for you — old skills atrophied, and training for new artists weakened. It wasn’t a learning environment.

But some pushed back against this trend. In the 2000s, the TV classics Samurai Jack and Avatar: The Last Airbender were both animated in South Korea, where outsourcing dominates the animation industry to this day. These two shows offered their artists something more than an assembly line.

When Genndy Tartakovsky approached the studio Rough Draft to animate Samurai Jack, he gave them a proposal. “I wanted it to not just be an overseas studio. I said, ‘Look, if you guys really commit to this show … then I’ll put your names in the front,’ ” he said. “And then they did, and then we gave them front credit, and then when we won awards, they won awards.”

Rough Draft became a more creative force on Samurai Jack than was typical for outsourcing — it brought ideas. It was a collaborator. Sure enough, when the series picked up an Emmy for “Outstanding Animated Program” in 2004, animation directors Yu Mun Jeong and Jae Bong Koh were listed among the winners. South Korea’s press celebrated their victory.

On Avatar, the involvement of the Korean teams at Tin House, MOI Animation, DR Movie and JM Animation was pivotal to the series. The Canipa Effect has a good and accurate video essay about it, but the gist is this: Korean animators were allowed to animate, to design characters, to suggest ideas and to refine the series.

It was the opposite of Gamma Productions. As animation director Jae Myung Yoo said:

In the animation industry, we have what’s called an indication. An indication contains information on each scene, giving instructions on every fine detail, including the movements of the characters as well as how and when they should move. This actually makes the animated characters’ movements appear robotic. So, when we were asked to work on the pilot film of Avatar: The Last Airbender, we asked the producers to scrap the indication because it’d prevent us from making the movements appear natural.

It worked. The animators in South Korea were put in charge of timing their own animation — they were treated like animators, and not like machines. In fact, artists up and down the pipeline were made into active participants in the series.

The Avatar DVD includes a 25-minute documentary about the outsource teams. In it, you see everyone from directors to designers to checkers offering an opinion about the production. They’re open about what worked and what didn’t — it’s a fascinating and surprisingly technical peek into the process. It’s less outsourcing and more international co-production.

“Compared to other animation work, including the ones I’ve been involved in, Avatar had a very different work system,” said Jae Myung Yoo in that documentary. “How do I say this... it provided an environment where the actors can act freely, and could also put their own thoughts into action.”

This was a great thing, and the results spoke for themselves. It brought out the good parts of American work with outside partners, while minimizing the bad. Artists in the documentary consistently say that they “learned a lot” — it was a learning environment, like any production should be.

It’s always a sign that artists are being treated like artists, like how the Czech animator Zdeněk Smetana recalled his years with Deitch as his “university” education. For all the challenge, it wasn’t drudgery. As outsourcing continues today, American teams would do well to take a lesson from the projects that did it right — treating partners like the partners they are.15

2 – Newsbits

Birds, By the Way is a hilarious, super charming film from Russia, and it’s finally on YouTube. Director Alla Vartanyan made it at Soyuzmultfilm, although she now lives abroad.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from Russia: Sostav covered an animated children’s film bankrolled by Gazprom and made with AI. This is nightmarish viewing, via YouTube.

Chie the Brat, the classic Japanese TV series by Isao Takahata, is out in English. Discotek Media released its five-disc Blu-ray set this week.

In Spain, the Animayo festival gave a top award to Remember Us by Pablo Leon. He’s a California animation worker who’s branched out with an independent film about the Salvadoran Civil War. Find the trailer here.

Ferenc Mikulás of Kecskemétfilm, based in Hungary, is stepping down as managing director after 53 years. The studio is best known for Hungarian Folk Tales.

Natália Azevedo Andrade of Portugal will pitch her new project, There Might Be Nothing Here, at Annecy. Its trippy teaser is already public. Andrade’s film Thorns and Fishbones really impressed us a couple of years ago, so this is one to watch.

The Japanese character designer Kenichi Konishi (Princess Kaguya, Tokyo Godfathers) is going to direct a film at Studio 4°C.

In China, historian Fu Guangchao did an hour-long video tour of his museum exhibition of Shanghai Animation materials. He also spoke to The Paper about his decade-plus quest to preserve animation history, and the anxiety of trying to save what’s rapidly disappearing.

The American series Scavengers Reign, a highlight of 2023, is now on Netflix.

Lastly, we looked into the importance of stillness in animation — and the many controversies and dueling philosophies around this idea.

See you again soon!

From the Chattanooga Daily Times (September 27, 1959).

From The Lost Episode: History of Mexican Animated Cinema (El episodio perdido: historia del cine mexicano de animación). Most of the other details in the Rocky and Bullwinkle section derive from The Moose That Roared and The Art of Jay Ward Productions.

Snyder loved puppet animation, and it was his studio that brought Jiří Trnka’s film The Emperor’s Nightingale to America. He’d caught it at a screening in 1949. “It was the most amazing animated movie I’d ever seen,” Snyder said in 1951. “The next day I quit my job and flew to Europe to get the American rights.” See The Evening Sun (November 7, 1951).

From Deitch’s blog and a documentary he posted there, which we used a lot. The $5,000 figure comes from his book How to Succeed in Animation, used a few times.

From a 2003 interview with Bedřich, as collected in Animation and Time (pages 340–341).

You can watch Madeline’s Rescue and Madeline and the Bad Hat via the Internet Archive, although the music tracks are unfortunately warped. Still, it’s fascinating to see the differences in sensibility between UPA and the Czechs.

From The Daily Item (October 27, 1961).

From the Evening Vanguard (March 11, 1964).

Date from a Broadcasting article.

From Anime: A History, the source for Clements’ quotes and many of the details about Mochinaga today.

From Du’s book Animated Encounters, another important source.

In 1980, Shanghai Animation director Te Wei visited the United States, and the topic of wages at the studio came up. The Weekly Free Press (May 8, 1980) related that “filmmakers’ salaries are not more than $200 a month.” Adjusted for inflation, that’s around $800.

From Chinese Animation and Socialism.

From Comics Art in China.

Today’s story is a reprint of one we ran on April 14, 2023.

Was a great article last year, still is.

I do end up wondering a bit about the current state of animation outsourcing. Is South Korea still the main player? I heard there's a lot going to the Phillippines now (from both Japan and the States), and that other countries like India are becoming more popular for it, but I don't have any numbers. Presumably European arthouse animated films use outsourcing - how does that look compared to the US and Japan? Have there been any more notably positive collaborations since the days of AtlA and Samurai Jack?

I always think it's a tragedy that, while South Korea has one of the largest animation industries in the world, there's so little interest in domestic South Korean animation. I got into aeni for the 'Animation Night' project and found all sorts of cool things - you have brutal social realism in the films of Yeon Sang-ho like *King of Pigs*, beautifully drawn pastoral nostalgia slice-of-life and magical-world stories in films like *Green Days - Dinosaur and I* and 'My Beautiful Girl Mari*, crazy chaotic flash in *Aachi & Ssipak*, really strikingly moody cyberpunk in *Sky Blue*/*Wonderful Days*, a strong Ghibli tribute in *Yobi the Five-Tailed Fox*, even cheerful shōnen in *Ghost Messenger*. A lot of it ends up feeling stylistically very similar to anime, but there's an interesting realist streak in a lot of these films which seems to be something Korean animators are very good at (much to the benefit of AtlA and Korra). And that's not even to get into the work of Peter Chung, who worked in both the US and Japan but still kept close ties with Korea throughout his career. I wish there was more appreciation abroad for aeni, just like with donghua!

And speaking of North Korean animation, there was a film called *Empress Chung* made in 2005 as a collaboration between SEK in North Korea and AKOM in South Korea, largely driven by the efforts of director Nelson Chin who spent eight years bringing it about. It sounds fascinating, and won awards at Annecy, but never got an international release so almost no trace of this movie seems to exist online anymore. I hope one day I'll be able to track down a copy. There has to be such a fascinating story there.

Thank you for this, a fascinating article. I'm a TV animator in the UK, and I've found that the American shows I work on aren't outsourced in the conventional way, as often the directors, story artist and everything on are in the UK. But the client and money will be in america. Which then heavily influences the show, so we often make work intended to appeal to an american audience first, even though the whole creative team live and work in the UK.

It's a weird set up, but it pays better than local or indie productions, which seems to follow the examples you gave in Japan and China.

Also from now on I'll measure the quality a project by how much the team is learning on the job as well as the final output. Learning is so important to keep the animation industry doing new and interesting work!