Welcome back! We’ve brought another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And here’s the agenda for today:

1 — the story of A Da’s Chinese classic 36 Characters.

2 — the animation news of the world.

3 — the retro ad of the week.

We publish new issues every Thursday and Sunday. If you haven’t already, you can sign up to receive our Sunday issues right in your inbox, every weekend:

That’s the intro — now, let’s go!

1. 36 Characters across the globe

In the early ‘80s, China was opening up — and animators were flourishing again. They’d survived the terror of the Cultural Revolution, which had persecuted artists like themselves during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Now, it was time to rebuild and branch out.

Maybe the most celebrated figure in this rebirth was A Da, a veteran artist who’d helped to invent ink-wash animation in the ‘50s. He returned to work with a vengeance after Mao’s death, taking on films like One Night in an Art Gallery and Three Monks in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Both projects represented a new dawn for Chinese cartoons.

Part of that new dawn was the wider world. China was a closed society no longer. A Da’s Three Monks and a number of other projects made at Shanghai Animation Film Studio started to travel. China’s animators did, too — A Da was one of them.

In 1982, A Da went to the international “Animafest” festival held in the city of Zagreb. Dining at a hotel, he and a few companions encountered an American animator named David Ehrlich. The Chinese attendees kept to themselves and stayed very quiet, as Ehrlich recalled. He spoke basic Chinese, so he decided to approach them:

In my most practiced Beijing accent, I smiled and said, “ni hau.” Suddenly all four Chinese broke out into giggles and stood up from their table to shake my hand. After the initial introductions and chat from my Chinese 1 class about how they enjoyed breakfast and the city of Zagreb, my Chinese vocabulary found its natural limits, and I rose to go to the festival center. As I reached the street, I turned to see one of the Chinese following me. He gave me the biggest smile I had ever seen and announced in absolutely clear English, “My name is A Da. I learned English at the Peter Pan School in Shanghai when I was a child, but please don’t tell the other Chinese. China is still a little funny.”

In fact, A Da spoke four languages, and it wasn’t a secret to people who knew him. (One giveaway, to quote director Yin Xiyong, was that “he never needed an interpreter when going abroad.”1) And so A Da became fast friends with Ehrlich, forging an international bond that would change both of their lives.

A key symbol of that bond was A Da’s film 36 Characters (1984).

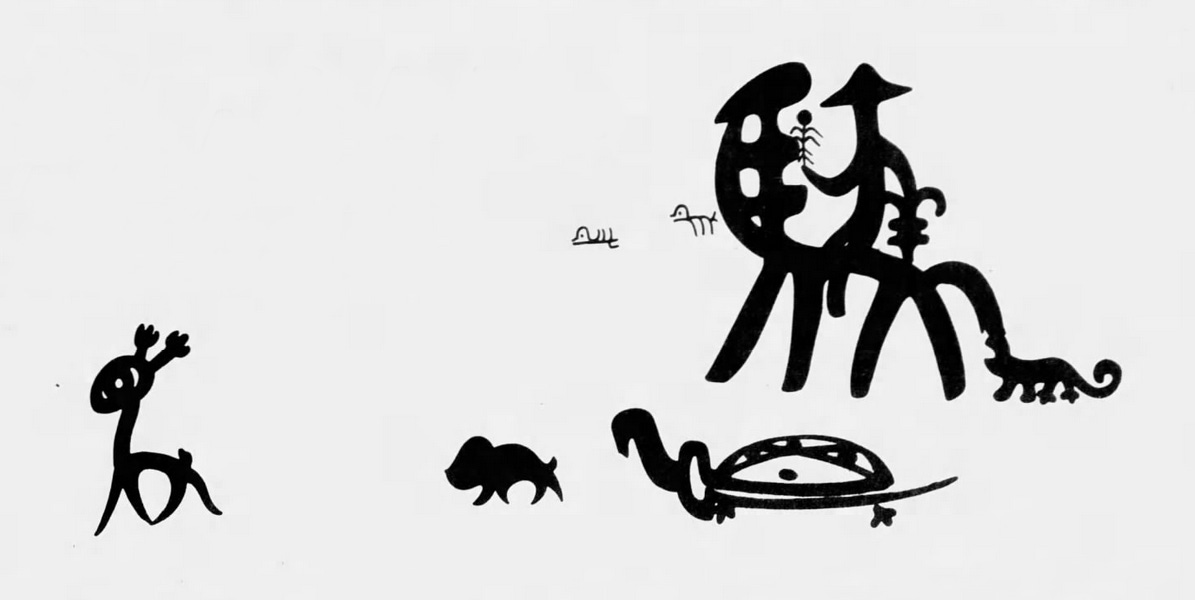

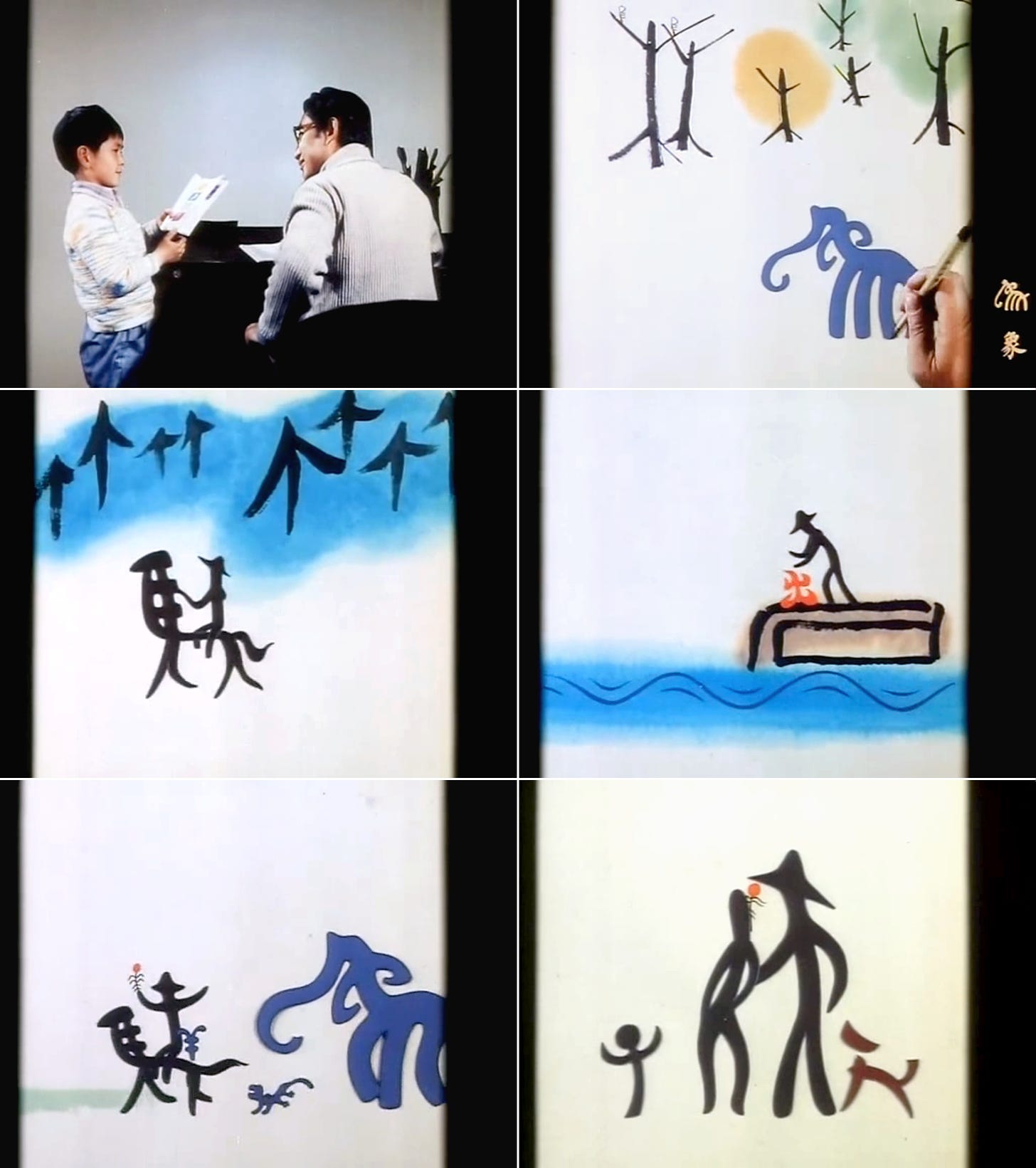

36 Characters is a cartoon about writing. A father teaches his son that certain Chinese characters come from ancient “pictographs” (similar to hieroglyphics). The father’s stop-motion hand draws them — and they spring to life as hyper-stylized elephants, water, rain and people. It’s something like a gentle Duck Amuck, but about the aesthetics of ancient China.

The concept is ingenious, and A Da didn’t take credit for it. “I got the idea at the Zagreb Festival four years ago, from my friend David Ehrlich,” he remarked in 1986. As he told the Los Angeles Times:

I use Chinese characters every day, but I never paid attention to them. [...] They really are based on pictographs: for example, the character for horse has four legs and a tail, which can be animated.2

A Da first developed Ehrlich’s idea into a children’s animation workshop, which the pair oversaw at Annecy in 1983. It was such a success that A Da went back to Shanghai to make his own version of the film. That wasn’t surprising — the concept for 36 Characters perfectly matched his creative philosophy.

Like most Chinese animators of his generation, A Da believed that Chinese animation should be Chinese — in aesthetic, plot, concept and all the rest. His intended audience was both local and international. “I want to make films that will introduce Chinese music and art to people in foreign countries and also show Chinese people their cultural heritage,” A Da said in 1984.

Back at Shanghai Animation Film Studio, A Da directed and designed 36 Characters with a talented team. The studio was the animation hub of China at the time. (“They are over 500 people working there … 200 of them are auteur in their own right,” he noted.)

Alongside the charming design of the pictographic cast, and the smart way that the film uses stop-motion humans to tell the story, A Da added another inventive trick. That was the shape of the screen. According to Yin Xiyong:

Our traditional television screen, what we called 720576, is a standard-sized screen, a rectangular one. However, in 36 Chinese Characters, A Da used a square one. Today, many people say that Feng Xiaogang innovated with his circular screen [in I Am Not Madame Bovary], but A Da’s innovation long preceded it.

This square screen, which A Da also used in Three Monks, has both an artistic and practical purpose. In the dark space to the right, the artists draw the pictographs and their modern descendants whenever they turn up in the story — adding a strong educational element.

Really, it’s fair to call 36 Characters an educational film. It originated in teaching, and A Da kept using its idea that way. Shortly after completing the film, he toured the United States in 1984, bringing several Chinese cartoons with him. Along for the ride was the storyboard for 36 Characters — which A Da used to teach American schoolkids how to animate Chinese pictographs.

“His visit, orchestrated by Brookfield animator David Ehrlich and sponsored by the Vermont Council on the Arts, is a small triumph for [Vermont],” reported The Times Argus, “since there has only been one other visit to the U.S. by a film producer from communist China.”

The trip went spectacularly — bursting with life, A Da was a hit with kids. It was another highlight of A Da’s friendship with Ehrlich, and of his own global outreach. In 1985, A Da would join the board of the International Animated Film Association (a first for someone from Shanghai Animation, according to Yin Xiyong), helping to make Chinese cartoons a recognized art outside China.

Ultimately, 36 Characters went full circle. In 1986, it appeared at Animafest — and won in the educational film category. The project dreamed up in Zagreb triumphed in Zagreb, continuing to spread the culture that A Da held so dear. With 36 Characters, he “introduced Chinese writing [...] to a world audience,” wrote Yin.

And you can find the film with English subtitles below:

2. Global animation news

Finishing a film in war-torn Ukraine

As Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine continues, one thing hasn’t changed — Ukrainian animators are still working. And this week brought an especially intense glimpse at how animating looks in wartime. It came from a behind-the-scenes video for Mavka: The Forest Song, an upcoming animated feature from Ukraine.

Animagrad, based in Kyiv, has been making Mavka for upward of five years. It was nearly done when Russia attacked. As producer Iryna Kostyuk says in the video:

When the war started, the normal workflow became quite impossible … but the production stopped only for a few days, because the studio rearranged the processes to allow the team to resume their work, and to work on the film even under these circumstances.

We hear from director Kostyantyn Fedorov, who supervises Mavka remotely in a barricaded room. From art director Kristian Koskinen, who recalls the bomb that went off near his house when his wife and child were at home, and how the three of them hid in their basement for nine days. And from animator Natalia Lenskaya, who found herself locked down during the horrific Bucha occupation.

“We had no heat, no electricity, no water, no connection,” Lenskaya says. “We saw what happened to those who did not get to the evacuation corridor, and I will never forget what I saw.”

The video explains that 42 members of Mavka’s team, along with their families, are currently displaced inside and outside Ukraine. Five members were trapped in Russian-occupied territory, but are now free. And four members have joined the military. Yet, after giving us these statistics, the video concludes:

Mavka: The Forest Song will be delivered this year on time.

Domestic release will take place right after our victory.

Mavka was pitched today, Sunday, at an international film market in Cannes. A special Cannes screening of Mavka’s completed sections is scheduled for tomorrow.

Best of the rest

The week’s big story was Netflix Animation again. See Cartoon Brew’s explainer: more shows canceled, 70 positions cut. Artist Tom Smith argues that Netflix’s strategy has backfired: “operating at such a massive loss that no one else could possibly compete,” then cheapening the product “once the damage was done.”

In Japan, the Totoro Fund for preserving the natural world just acquired over 46,000 square feet of new forest land. The cost was roughly $217,831.

China’s biggest animated film ever, Nezha (2019), is getting a sequel. The project was confirmed and approved by the Film Administration this week.

There’s an impressive new trailer for the ambitious Nayola from Portugal.

A Chinese indie feature (The Mermaid’s Summer) made entirely by husband-and-wife team Shen Xiaoyang and Xiaoyue is due in 2023. It took six years, 18-hour days, nine months a year — the other three went to commercial work to pay the bills.

In America, the Brooklyn-based Animation Block Party is showing the great Barber Westchester this year. (Also, on June 1, the event opens for submissions.)

In America, the ex-football player Trevor Pryce (Kulipari) is using a mix of state and investor money to grow his animation studio Outlook in Baltimore. He hopes to “add 150 full-time jobs over the next two years,” per The Baltimore Sun.

Another American story: Pixar revealed Elemental, a feature film due 2023.

In Russia, April saw more than a 50% decline in theater attendance year-over-year. Now, the government has refused a major bailout petition by the country’s failing theaters — citing the need to support more critical parts of the economy.

We looked into three animated gems from 1960, made in Yugoslavia, America and China. They tell us a lot about how that era played out around the world.

Lastly, accompanying a deal that lets Disney digitally reanimate Stan Lee into the foreseeable future, rightsholder Genius Brands gave us the week’s scariest corporate spiel:

We are proud to be the stewards of the incredibly valuable rights to Stan Lee’s name, likeness, merchandise and intellectual property brand. And, there is no better place than Marvel and Disney where Stan should be for his movies and theme park experiences.

We hope you’re enjoying our issue today! Thanks for giving it a read.

The last part of this newsletter is for members (paying subscribers). Below, we look into a retro ad from 1966, animated by the renowned Bill Littlejohn — best known for his Peanuts animation. We relied on an obscure, imported book to research this one. It’s fascinating stuff.

Members, read on. Everyone else — we’ll see you next time!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.