Welcome! We’re back with a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And here’s our agenda for today:

1 — how One Night in an Art Gallery upturned Chinese animation.

2 — the world’s animation news.

3 — the retro ad of the week.

With that out of the way, let’s go!

1. ‘We were not afraid’

Not many countries have animation traditions as rich as China’s. Its animators have pushed forward for a hundred years, creating one wildly unique style after another. In the 1950s, when Chinese cartoons first hit their stride, animators in Shanghai even invented the still-secret technique of ink-wash animation.

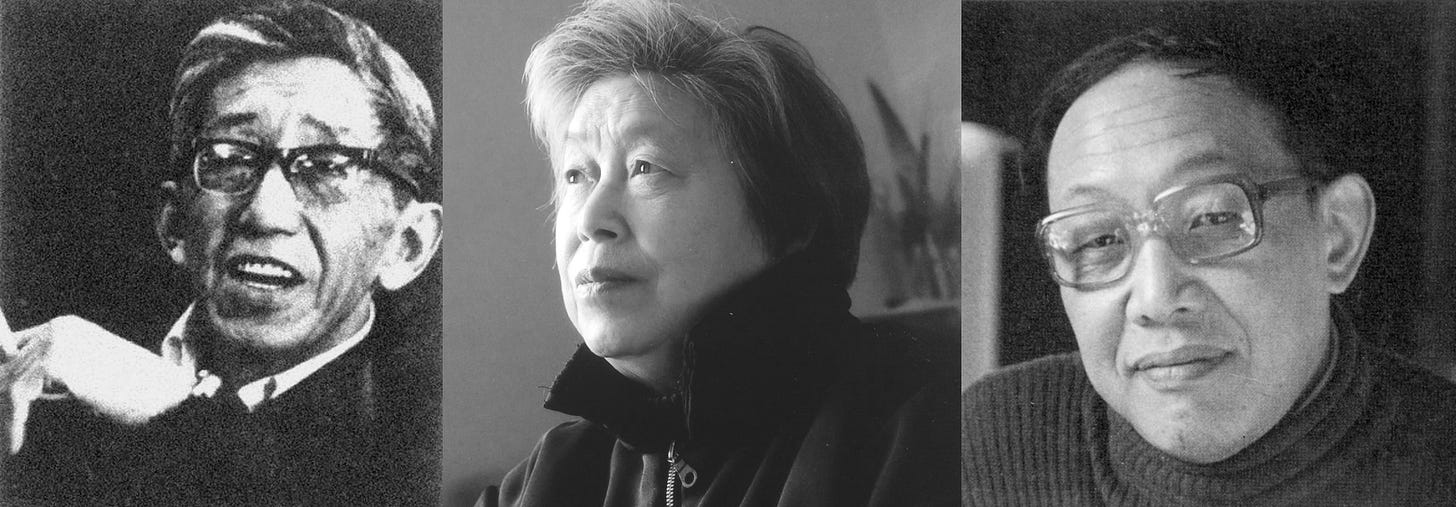

That first ink-wash film, Little Tadpoles Looking for Mama (1960), was an effort by the entire team at Shanghai Animation Film Studio. A few major names involved were Te Wei, the studio’s leader, and the young animators Lin Wenxiao and A Da. All were destined for great things.

But, if few countries can boast an animation heritage as rich as China’s, even fewer can claim to have hurt animators like China did in the years after the release of Tadpoles.

That’s because the animators in Shanghai were prime targets for the Cultural Revolution. Spearheaded by Mao and his so-called Gang of Four, the plan was to purify China. Counter-revolutionary thought had infected the country, they claimed. Anyone might be an enemy of progress, a reactionary, a secret saboteur — someone who (somehow) would bring both capitalism and feudalism to China.

High on the list of suspects were the old, experienced and educated, especially artists and intellectuals. The Shanghai animators ticked many of those boxes. It didn’t help that the fantasy elements in their cartoons, like talking kittens, were declared escapist — an opiate of the masses, more or less.

Animation Obsessive is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you’d like to support our writing and research, the best way is to take out a paid subscription.

And so, as the 1960s wore on, things got bad. First came the end of artistic freedom, as the censors enforced a string of bizarre demands. One Shanghai animator recalled:

During the Cultural Revolution, we were required to criticize feudalism, capitalism, revisionism, kittens, puppies and Disney … Thus a number of animated works on the topic of class struggle emerged, all of which drew on realistic subject matter.1

Shanghai Animation Film Studio even closed for a few years. Many of its artists were in labor camps by the late ‘60s. Lin Wenxiao, separated from her husband and children, planted vegetables. Te Wei, named a “capitalist roader” and “reactionary intellectual,” spent a year in solitary confinement with Mao’s writings before he was sent to work in the fields. Eventually, he joined A Da on a pig farm.

A Da remembered:

... we were all sent to the countryside, to what they called a “May 7 School,” because Mao said we had to reeducate ourselves from the peasant workers and soldiers [...] For three years, I fed pigs — hundreds of pigs — and dug canals. We were forbidden to do any artwork — it was considered counter-revolutionary — but sometimes I’d hide in the mosquito nets and sketch.2

Those sketches were, usually, insulting caricatures of the Gang of Four. A Da was planting a seed here that would grow into something big, several years later.

In the early ‘70s, the artists returned to Shanghai Animation Film Studio to make propaganda. Yet they still faced absurd, even surreal demands from the censors. One cartoon by A Da, Little Trumpeter (1973), featured an innovative use of spotlights to single out the revolutionary hero and landlord villain. A censor blocked the film because it was forbidden to “train spotlights […] on reactionaries.”

Then fate struck. In retrospect, A Da said that “1976 is the most important year for our China.” Why? “First Zhou Enlai died, then Mao. In October the Gang of Four are out.”3

China’s leadership changed almost overnight, and the Cultural Revolution soon fizzled. At Shanghai Animation, joy was in the air. “We could even begin to dance again at that time,” Lin Wenxiao remembered. “In our studio!”

A Da started to publish his insulting caricatures in the newspaper. They formed the basis of a new cartoon — one dedicated, openly, to breaking the studio’s creative bonds. This was One Night in an Art Gallery, a project started in 1977. According to one artist:

… we studio animators, like all literary and art workers, were experiencing an ideological emancipation. At the time, it was called the “second liberation.” It was in this emotional atmosphere that [screenwriter] Bao Lei wrote the script.

It was the dawn of a new era. “When we began this film,” Lin Wenxiao said, “we were not afraid.”

A Da and Lin Wenxiao co-directed One Night in an Art Gallery at Shanghai Animation Film Studio, which Te Wei was leading again. The team was supercharged. “When the Gang of Four finally fell in 1976, most of us thought only of drawing better than we had done,” Te Wei later said.

The resulting film was part of “a tremendous release of artistic energy that had been repressed for ten long years,” according to historian David Ehrlich.

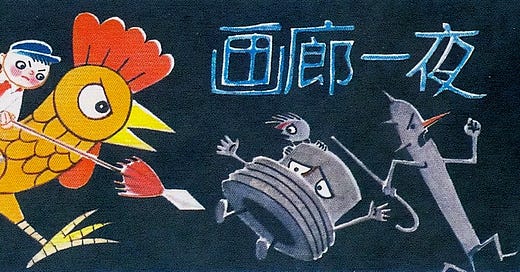

One Night’s concept is straightforward. Two goofy bad guys, namely a spiked bat and a stack of hats (adapted from A Da’s caricatures), arrive to inspect a gallery of children’s art. Everything looks reactionary to them. A painting of a footrace is anti-cooperation — a painting of a schoolteacher brings to mind Confucius. They spot one of those “capitalist roaders,” and much more.

So, they begin to knock down and cross out artwork. They whip themselves into a frenzy, wrecking the gallery and painting the phrase “completely smash” (彻底砸烂) on the ground. Animator Fung Yuk Song has explained that “the slogans used [in the film] were those we personally experienced during the Cultural Revolution.”

That specific phrase, “completely smash,” had played a crucial role in Maoist propaganda. Even in the new China, its use in One Night alarmed the censors. Fung Yuk Song again:

[It] was considered inappropriate, because at that time certain regulations meant that we could not depict the chaos of the Cultural Revolution too directly. But I said that “the ‘completely smash’ scene must be used, because this was a typical symbol of the Cultural Revolution.”

Ultimately, the scene survived. And so does the art gallery in the film — as the inhabitants of the paintings come to life, band together and repair the damage. In the end, the censors are beaten, literally and figuratively.

Just as bold as One Night’s message is the film’s execution. It tosses out any trace of Revolution-era aesthetics — it’s cartoony, zany and immensely fun. The animators went wild, packing the film with the kind of visual comedy you might associate with the Zagreb School. Fung Yuk Song animated one character, an informant, who breaks every rule of physics, even flattening out to fit under a door.

But there’s also beauty to the animation. When the children emerge from the paintings and start to clean, especially as they skate and dance across the floor, it’s surprisingly emotional. The animators had an eye for human detail here — not just gags. Touches of reality blend with the cartooniness to create something new.

Released in 1978, One Night resonated with the public and set the stage for a new kind of Chinese cartoon. It was Lin Wenxiao’s directorial debut — she became a major player in the field, as did A Da.

While it’s not well known outside China, and great-quality copies are tough to find, One Night in an Art Gallery contains an energy that transcends time and borders. There are so many ideas here, executed so well, that you don’t need to understand all the specifics and references to feel the effect. The sense of freedom still comes through.

As David Ehrlich wrote, One Night:

… signaled to the Chinese audience that the bad times were over. And with the exuberance expressed by this film and the reception given it by audiences throughout China, One Night in an Art Gallery began the period that Chinese animators sometimes call their Second Golden Age.

2. Global animation news

The Ukraine-Russia update

While war rages, the business of animation continues. Ukraine’s industry is working to stay alive. We saw that this week when Glowberry, a studio based in Kyiv, announced an agreement with Warner to bring its cartoon series Brave Bunnies to 20 territories. Britain’s Aardman organized the deal.

And Ukraine has “a dedicated country pavilion” at MIPTV in Cannes, where businesspeople from across the globe are cross-pollinating right now. (MIPTV has banned Russian attendees.) Ukraine hopes to ink deals for projects like its animated feature Roxelana.

Here’s a quote from the pavilion’s coordinator, via World Screen:

The Ukrainian audiovisual industry is powerful […] These facilities did not disappear during the two-year COVID-19 pandemic. On the contrary, during this time, Ukrainian media produced many stories and projects for all tastes, which we are ready to offer to foreign partners. And now we need this cooperation more than ever to pass with honor our new terrible test of strength.

This kind of global outreach has, to put it mildly, decreased for Russia. The country’s animation industry is trying to rally, and to make up for the loss of international growth brought on by boycotts and sanctions. Survival hinges “on how much domestic animation will be supported by the state,” said TV producer Igor Shibanov this week.

Most recently, the government allocated one billion rubles to support cultural projects. It plans to extend the deadlines for state-funded films and to hold several extra “Cinema Fund competitions” in 2022. Roskino, the state film agency that covers international markets, is reorganizing to focus on India, Turkey, China and other countries that haven’t cut business ties with Russian media.

It’s all a little dry and technical — but the panic is real, and so is the damage to Russian animation. As Kommersant reports, much of the revenue of Russia’s biggest cartoons, like Kikoriki and Masha and the Bear, comes from outside Russia. Isolation hurts, and it’s brought along a loss of access to animation software.

As Russia’s invasion starves artists back home, the state also suppresses those who dare to speak up. This week, even the venerable Russian web cartoon Masyanya (2001–) had its site blocked. That came after its creator, the Israel-based Oleg Kuvaev, published a very forceful, and very popular, anti-war and anti-Putin episode.

“In less than 24 hours, more than 500,000 people watched the episode,” reported RFE/RL.

Best of the rest

News arrived this week that we’d lost Carl Bell (91), an animator whose four-decade career took him to almost every major studio in America.

American animator Ian Worthington, also known as Worthikids, dropped a very funny new episode of Bigtop Burger. (We explored his Blender animation process in a recent issue.)

The stage version of Spirited Away is a success. It premiered in Tokyo and will now travel across Japan. See Animation Magazine for great photos.

On the subject of MIPTV in France, Animation Magazine also has eight series from the event to keep an eye on.

At the Russian box office, the Riki Group’s animated feature Finnick took the #1 spot in its debut weekend. Sony Pictures was signed to distribute it, but a subsidiary of Gazprom has assumed that role.

We have a second teaser trailer for Sunao Katabuchi’s upcoming film about ancient Japan. Meanwhile, there’s talk on Twitter about the techniques he’s developing with the free software OpenToonz.

A trailer has emerged for the American film The Sea Beast, directed by Chris Williams (Big Hero 6).

Anime News Network has an in-depth feature on the American voice actors talking about a union. “Now that Funimation and Crunchyroll are merging, can we get some union dubs?” asks veteran actor Stephanie Sheh.

In Japan, Crunchyroll shared viewer data with anime producers to help them tailor their work for the global market. One takeaway? “Titles aimed at female audiences over-perform due to unmet demand,” ANN reports.

Lastly, we looked into the amazing career of the American animation legend R. O. Blechman, now in his 90s.

Hope you’re enjoying the issue! Thanks for reading so far.

The final part of today’s newsletter is for members (paying subscribers). Below, we dive into a retro commercial from the 1960s, starring the cast of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. It’s a fascinating slice of history.

Members, read on. For everyone else, we’ll see you in the next issue!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.