Miyazaki's Sherlock

On 'Sherlock Hound,' plus news.

We’re back! Thanks for checking in. This is the first 2026 edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter — we’re fresh off our break, and ready to explore more stories from across the globe.

Here’s the plan for today:

1. How Sherlock Hound (1984–1985) came to be.

2. Animation newsbits.

Now, as always, let’s go!

1. Scrambling

At one point in his animation career, Hayao Miyazaki was looking for work. Ghibli wasn’t there. He took jobs as they turned up.

Directing wasn’t his dream, initially. “Even today I don’t like being pegged just as a ‘director,’ ” he said in the late ‘70s. By then, though, he’d already accepted and overseen Future Boy Conan, his first time in the spotlight. He followed it with The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), his debut feature, despite his reservations about that project.1

To Miyazaki, The Castle of Cagliostro was a rehash — leftovers of the old Lupin the 3rd era. He and his team threw the film together in under five months, and it bombed in theaters. “You can’t use a sullied middle-aged guy to create fresh work that will wow viewers. I realized I should never do this again,” he said.2

Yet Miyazaki kept taking the work in front of him. Soon, he accepted two more Lupin projects — suffering as he went.

He viewed himself as a bit washed up by 1980, more than 15 years after the start of his career. His “year of being mired in gloom,” he called it. Miyazaki was pushing 40 and having a mid-life crisis.3 “With every piece I made,” he said, “it was obvious that I was just trotting out everything I had done before.”

But the world saw things differently. Future Boy Conan and especially Cagliostro began to bring him a name.

In meetings abroad, Miyazaki’s work became a calling card for Tokyo’s Telecom, the studio behind Cagliostro. “You know, whenever I go to the US, I take The Castle of Cagliostro with me,” said company head Yutaka Fujioka in the early ‘80s. “Recently I invited 200 Disney staffers to see it — and, wow, there was applause, great applause.”4

Although he doubted his creations, Miyazaki put in a supreme amount of effort and care, always. It showed, and word of his ability spread. The Cagliostro screenings seem to have caught the attention of producers even in Italy.5 That was when the Sherlock Hound series came into Telecom, and into Miyazaki’s hands.

As it happened, Japanese animation was already big business in Italy. During the ‘70s, shows like Grendizer took over the country’s airwaves. The Italian theme song for Heidi: Girl of the Alps became a hit single. By 1980, animation from Japan was popular enough in Italy to be controversial — writers fretted about the effect of its allegedly “reactionary and very sinister” content on kids.6

Tied to this boom was an exec named Luciano Scaffa.7 And, when business grew, he thought to take it beyond licensing: he wanted to co-create shows with Japan. As early as 1980, Scaffa was developing a series planned by Marco Pagot and his sister Gi, two important people in Italian animation.8 In Marco’s words:

… Rai 1 director Luciano Scaffa decided that, in order to bring new ideas into the Italian market, the only way was to make co-productions with the most powerful market of the period, the Japanese one. He chose a series of Italian projects and brought them into Japan. Among them is one of my projects, which generates a certain degree of interest: Il Fiuto di Sherlock Holmes.

That title is a pun: fiuto refers to the sense of smell, but also to intuition. Basically, the Pagots imagined a cartoon-dog version of Sherlock Holmes, to be animated by Japanese talent. The idea wasn’t crazy. Europe was doing more and more co-productions with Japan back then — one, Dogtanian, had a similar angle.9

Yutaka Fujioka was involved in this co-production wave. In fact, he’d built Telecom to make animation with foreign studios. It was a training hub — and a site for Japan’s best animators to reach world-class quality. “[W]ith this ‘co-pro’ system, you can use more than twice as much money and time. There can be no greater advantage than this,” he argued. Extra resources, Fujioka believed, meant higher quality and higher profits.

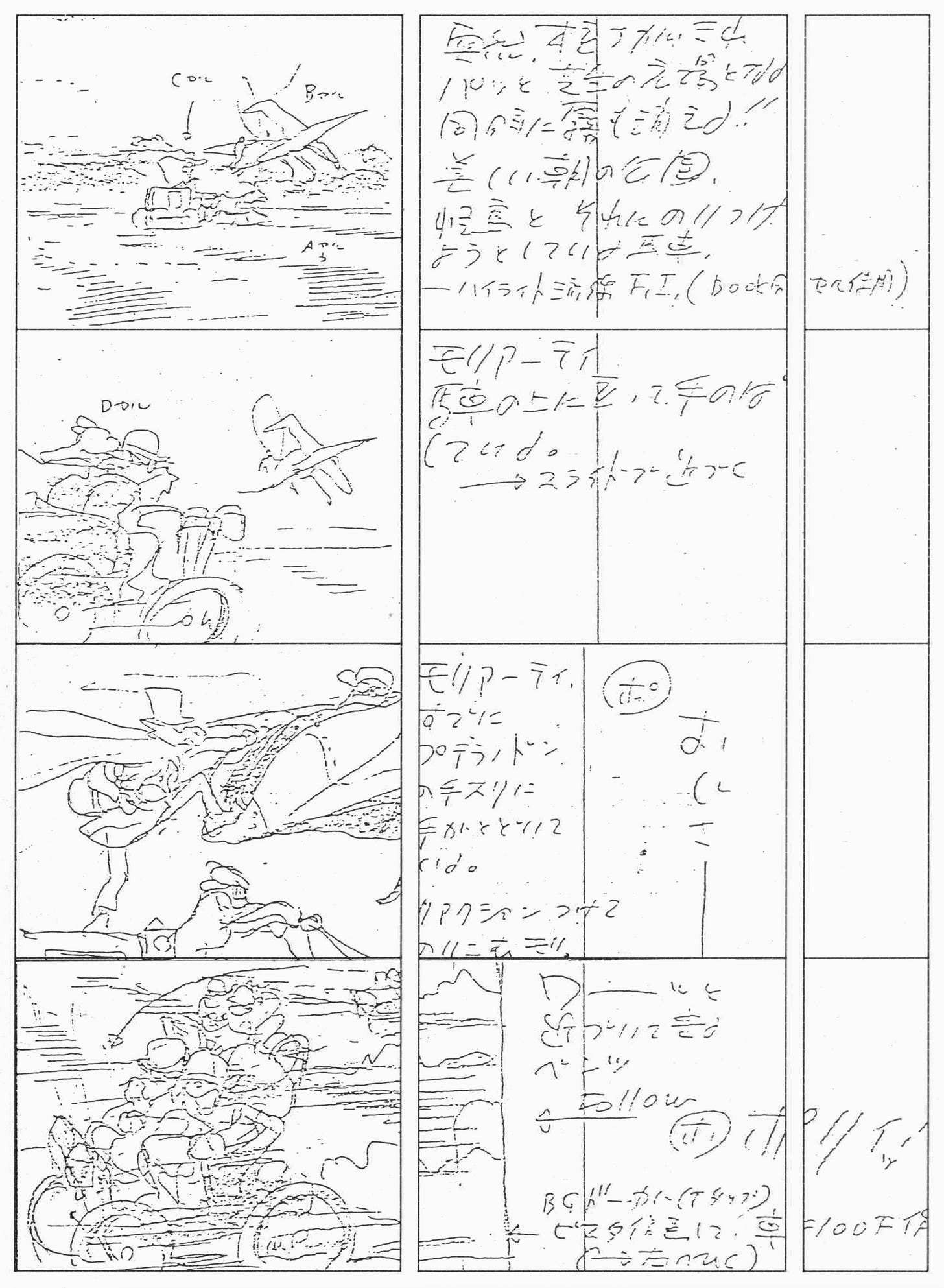

Telecom took the dog-Sherlock show, known today as Sherlock Hound, and put Miyazaki in charge. He began sketching ideas for it in April 1981.10

Right away, though, the outline worried him. Miyazaki approached art on a deep level — he thought about the worldview and meaning inside a story and its characters. “When the offer came, what struck me was the difficulty of the concept of a detective. These days, it’s hard for a knight in shining armor (seigi no mikata) to exist,” he argued. In the ‘80s, criminals and their messy motivations seemed to be more full of life than a good guy like Sherlock.

And why, Miyazaki kept wondering, did he need to be a dog?11

Miyazaki had been an idea guy since the ‘60s. Concept sketches flowed out of him — wild contraptions, zany stories. But he didn’t come up with Sherlock Hound all alone. He left a good deal of the prep to his crew, seemingly in an effort to train the new generation.12

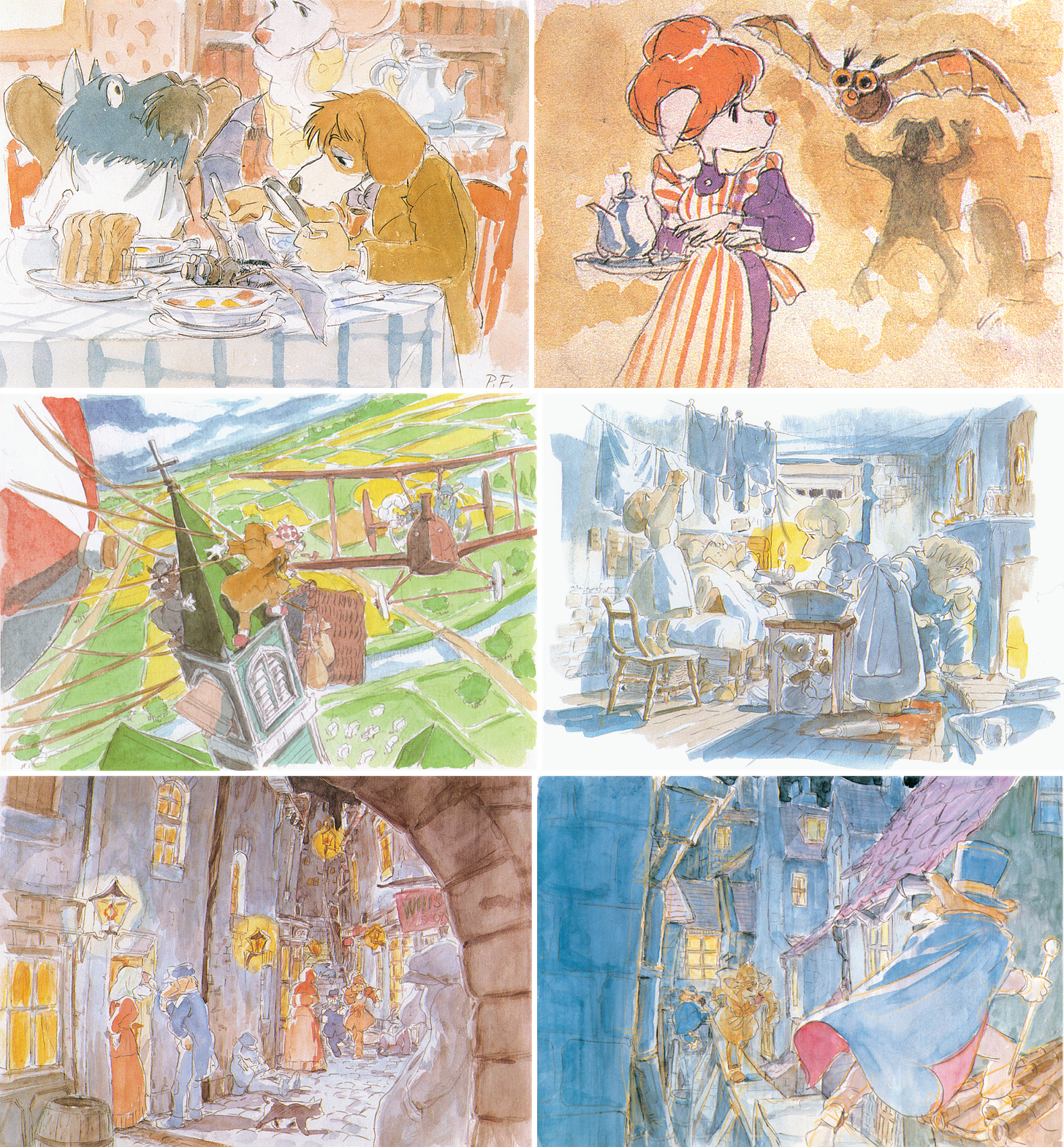

Doing concept art with him was Yoshifumi Kondo, who’d later direct Whisper of the Heart at Ghibli. Another was Kazuhide Tomonaga, animator of that iconic car chase from Cagliostro. They adopted Miyazaki’s pencil-and-watercolor style to illustrate the world of Sherlock Hound.

That world is a mashup of the late 19th century with 20th-century technology, Miyazaki said. Guided by research material from the British Council, the artists imagined the everyday lives of these dog-creatures.13 Still, they deviated. Miyazaki bent Sherlock Hound toward his own interests: flying machines, love, characters with complexes. He needed to be invested, even in a work-for-hire project.

“Even if it’s a co-pro, we have no choice but to create what we find interesting,” he said. “As long as Japanese children are happy [with it], we believe that Italian children will be pleased, too.”

In the process, the team scrapped the Italian plan for the look. Sherlock Hound was meant to be “flat” and “graphic” in the Pink Panther vein, Tomonaga said. Miyazaki wasn’t interested: “the other side was creating a two-dimensional world, but Miyazaki-san wanted to make a three-dimensional world.”14

Miyazaki’s goal was “space.” It had to feel like the characters were navigating real places of concrete sizes and shapes — every street, every room. In Tomonaga’s words:

If the perception of space is realistic, then, even if the characters do cartoony and comical things, it doesn’t look like a lie, right? The characters definitely feel like they’re moving with their feet firmly grounded.

It was an approach Miyazaki had picked up during his years as the right hand of Isao Takahata, on projects like Heidi. Takahata saw film as “a continuity of time and space,” Miyazaki said. The theory was that, when animation has a sense of realistic continuity, viewers treat even the absurd as believable.15

After going solo, Miyazaki stayed indebted to Takahata’s style. “I wonder what Paku-san would do in a situation like this?” he said often during Sherlock Hound, using Takahata’s nickname.16

In the summer of ‘81, after a few months of prep, an Italian delegation arrived to review Sherlock Hound. With it were Luciano Scaffa and co-creator Marco Pagot, then in his early 20s. “I was introduced to Hayao Miyazaki, who for me was still an unknown character, because he wasn’t yet so well known outside Japan,” Pagot said.17

Disputes broke out. From the beginning, Miyazaki was reportedly suspicious of Pagot, this “typical rich kid.”18 And the Italians weren’t happy about the new visual style, among other things. Miyazaki had even cooked up a plan to turn Sherlock’s landlady, Mrs. Hudson, into a human. Sherlock had feelings for her but was ultimately “just a puppy,” watching from the sidelines. (Mrs. Hudson reverted to a dog-person in the final show, which Miyazaki came to agree with.)

Still, after a few months, the two sides reached an understanding. Things like Sherlock’s drug addiction, shown in the concept art, were cut. But many of the team’s ideas, including that three-dimensional world, remained. And Miyazaki’s team got near-total control from there.

Production started at the end of ‘81. It was feature-level animation: the first episode used almost 10,000 cels by itself. Telecom’s artists appreciated that. These were people trained to animate and animate — it was their love. “They draw until they’re satisfied,” Miyazaki said. Late nights were the norm there.

But the workload was trouble for Miyazaki. Two of his deadlines ran into each other: as Sherlock Hound began, he was doing his new manga series Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Like he remembered:

It was standard operating procedure at Telecom to work till after midnight, but I used to sneak out around 11 p.m., worried that people would notice me leaving early, and drive home, switching my brain over to Nausicaä. Then I would sit at my desk in the middle of the night, desperately drawing manga pages and cursing. Then in the morning I would put my brain back on Sherlock Hound as I drove to the studio. I did this every day. While I was working at the studio I behaved as if I’d never heard of Nausicaä. If I saw a copy of Animage [where the manga ran] lying around I would flee the room.19

But he had a strong team to rely on. Yoshifumi Kondo’s character designs were undeniable, and his corrections to the animators’ work were top-notch. Nizo Yamamoto supervised the backgrounds with amazing care, down to the unique colors of individual bricks in the walls. Animators like Atsuko Tanaka drew relentlessly, even adding details that weren’t in the storyboards.

There was also a young student Miyazaki had brought in. His name was Sunao Katabuchi — and he had no screenplay experience until he pitched a script for Sherlock Hound. He submitted Blue Ruby (watch), which went into production. Then he did several more, and Miyazaki made him an assistant director. Sherlock Hound became a second school for Katabuchi, who learned everything from storyboarding to color design from the team.20

All of those people, and others on the Sherlock crew, later worked with Ghibli. Today, Katabuchi is one of Japan’s great directors, behind Princess Arete (2001) and In This Corner of the World (2016). Through this series, people got room to grow.

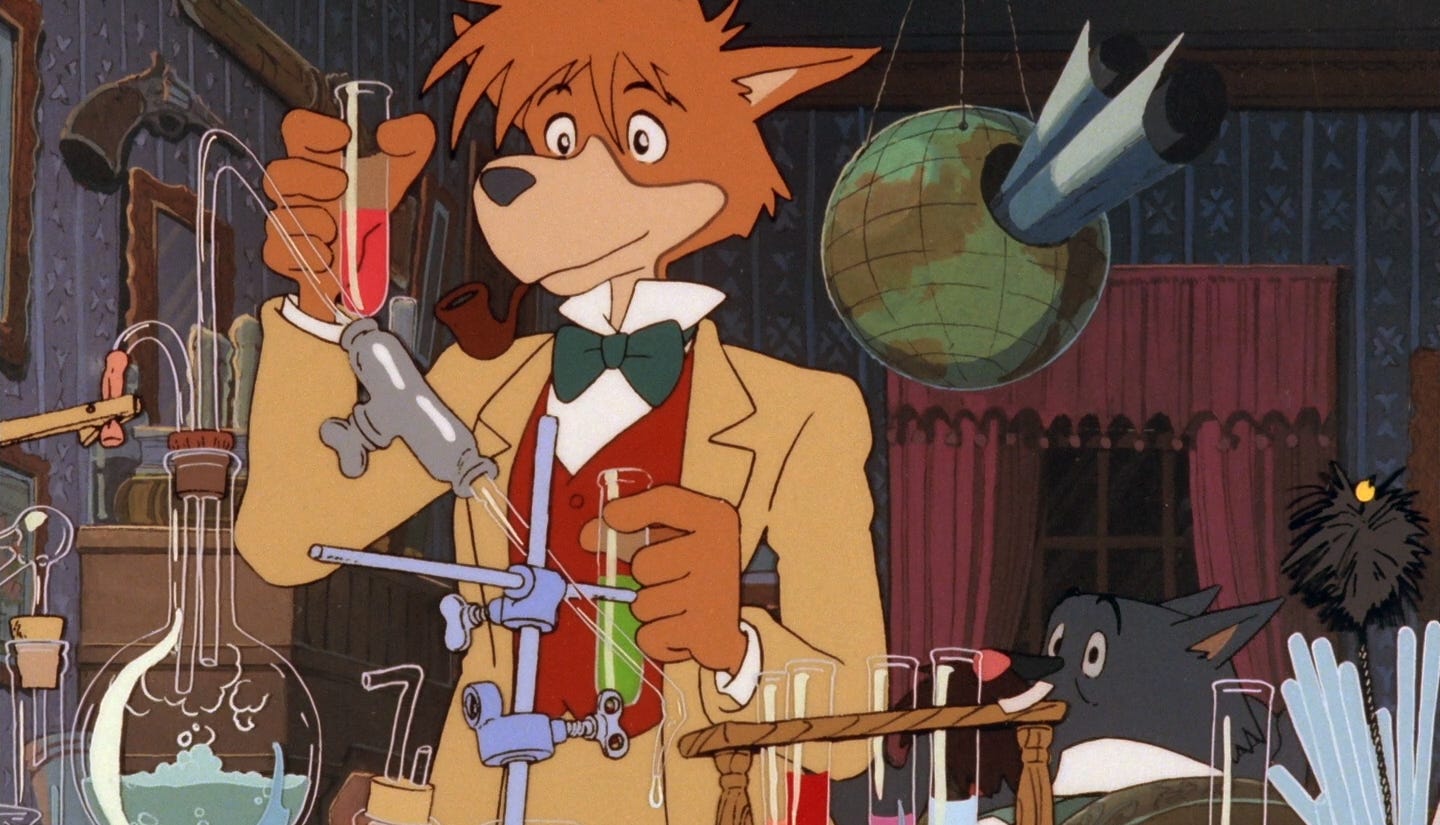

On the third and fourth floors of the Telecom building, in Tokyo’s Koenji district, the team created the first two episodes — Blue Ruby and A Small Client (watch). They were pilots. Both were examples of that world-class animation Yutaka Fujioka wanted to produce. These were true follow-ups to Cagliostro.

Miyazaki and the team weren’t working like most studios in Japan. He aimed to create old-fashioned slapstick adventures, and he used the dated term manga eiga (“cartoon movies”) to describe them. That term was popular in his childhood, when stuff like the Fleischer cartoons came over.21 It’s optimistic, zany, funny, exciting entertainment that owes a lot to Chaplin films like City Lights and Modern Times.

Katabuchi described the theory this way:

Animated films for children aren’t all “cartoon movies.” It’s more like… if I were to give you one similar example, it would be playing tag on the jungle gym as a child. Field athletics might also be close. I think there’s a kind of “mechanical environment” involved. A maze full of contrivances? A childlike sense of excitement for such a place. … Ah, yes, it feels like a “secret base.” It feels like the thrill and excitement of “kick the can.” Moreover, no matter what happens, no one dies or gets hurt.22

Those first two Sherlock Hound episodes are among the ultimate versions of this style of animation. When the Italians showed up again to review progress on the series, they were met with TV masterpieces.

But, again, there were concerns. Miyazaki’s series was becoming very, very expensive. And his auteurism didn’t mesh with the commercial approach planned for Sherlock Hound. The colors were too dark, the Italian side complained. And why was Smiley, Moriarty’s henchman, so weird-looking? And why was the series so wild?23

Miyazaki left one talk fuming. “They were doodling during the meeting, drawing things like a propeller on top of Holmes’ deerstalker cap,” he said, according to Katabuchi. “That kind of American TV cartoon nonsense was their intention all along.”

Notes from Italy led to edits in later episodes. The team had to redo part of Treasure Under the Sea, and the colors got brighter in all but Blue Ruby and A Small Client. But the trouble soon came to an end. In May 1982, production was interrupted due to a delay of funds from the Italian side. A few months later, Sherlock Hound shut down, with four episodes produced, two animated but unfinished and at least one partly storyboarded.24

It was a frustrating period. After the failure of Cagliostro, Miyazaki had been burned again. He and the team took this project and over-delivered — without much to show for it. Despite all its hype in the press, Sherlock Hound went into storage. Animage called it a “phantom masterpiece” in 1983.25

But the few who’d seen it knew what’d been achieved. Blue Ruby had a special showing in late ‘82, with no soundtrack, as none had been recorded yet. People were stunned anyway. This was something “fantastic,” one viewer recalled.26

In time, Miyazaki got another big chance: investors wanted him to adapt the Nausicaä manga into a movie. When that project reached theaters in 1984, Sherlock Hound screened with it in Japan. Two episodes — Blue Ruby and Treasure Under the Sea — were cut into a mid-length film. Even in a theater setting, the team’s work was strong enough to impress.27

Isao Takahata, too, got surprised by Miyazaki’s ability. It happened during the dubbing for the Blue Ruby section. There’s a pause in the dialogue when Sherlock speaks to Polly, the child thief, as she’s about to fall asleep. You feel it; the scene deepens. Takahata assumed it was an error on the team’s part. “Miya-san wouldn’t use a pause like that,” he insisted. But he and Katabuchi tracked down the instruction in the original storyboard. Miyazaki, clearly, had grown.28

Miyazaki kept growing, and he left Sherlock Hound behind. When the series resumed, after Italy started sending money again, it did so without his involvement. Another team came together — including some from the original group — and got the series on the air by the end of 1984. They followed many of the ideas laid down at the beginning, and his episodes sat beside theirs.29

This whole Sherlock project shouldn’t have been as interesting as it became. Miyazaki was scrambling from job to job in those years, taking what seemed doable, even if it didn’t sound promising. But he and the team put in so much care and effort that these projects — however unrealistic their deadlines, or questionable their outlines — were forced to be worthwhile.

It’s how a five-month movie like Cagliostro became a classic, and one of Disney’s and Pixar’s major influences. And it’s how people fell in love with a failed series like Sherlock Hound — whose charms still hit, more than four decades later.

2. Newsbits

Tonight at the Golden Globes, the animated film category went to KPop Demon Hunters.

In America, voting for the Oscar nominations in the animated short category starts on Monday. Two wonderful contenders are The Night Boots and Retirement Plan — on YouTube here and here, respectively.

Another from America: animator Coleen Baik released her film 엄마 나라 | Mother Land (2023) for free. It’s a haunting, personal piece that we recommend.

In Japan, while we were away, animator Tsuneo Goda spoke about his work with the Domo-kun character (his creation).

Empress Chung, a feature co-produced in South Korea and North Korea, disappeared after its theatrical run in 2005. That recently changed with its preservation on YouTube. (Thanks to Bryn for the tip!)

Next month in America, the Animation First festival will take place in New York, featuring Death Does Not Exist, restored shorts by Raoul Servais and more.

Also in America, and also in New York, Metrograph has been showing the films of Ugo Bienvenu (Arco) alongside the films that inspired him. Some of the screenings are over, but there’s still a chance to catch Princess Mononoke.

In Spain, animator José Martínez created a two-minute film in a five-day rush that he streamed continuously on Twitch. It’s now online, alongside its complete stream archive.

One last New York story from America: an animator, Rama Duwaji, is now the city’s first lady. See her work via her website.

Until next time!

The quote comes from “Speaking of Conan” in Starting Point, but is a revised reprint of the Future Boy Conan: Film 1/24 Special Issue interview from 1979. Yasuo Otsuka discussed his and Miyazaki’s concerns about Cagliostro in The Aspirations of Little Nemo, one of our key sources for this first part of the article.

From “Hayao Miyazaki on His Own Works” in Starting Point, used a few times.

Sunao Katabuchi has framed Miyazaki’s work from the late ‘70s as a mid-life crisis in the past as well.

From Animage (March 1982), used a lot today.

As Otsuka explained in Aspirations of Little Nemo, Fujioka had English subtitles made for Cagliostro and Takahata’s Chie the Brat (1981), which he showed many times in Hollywood. Otsuka claimed the screenings brought about the Italy deal.

The 1980 date comes from an article in Il Resto del Carlino (November 20, 1980), as quoted here. The Hollywood Reporter offered details about the Pagots. Those familiar with Porco Rosso will remember that Marco Pagot and Gina are key characters in the film — their names came from Miyazaki’s Italian co-creators here. He seems to have patched things up with Marco after that initial “rich kid” impression.

See Anime Cult #25 for the point about Dogtanian. Pagot confirmed that Sherlock was always meant to be a dog in a recent interview, included in the Il Fiuto di Sherlock Holmes comic published by Sprea Editori.

The date comes from The Art of Holmes, used many times today.

Miyazaki’s quote comes from the 1984 theatrical booklet for Sherlock Hound, via the Anim’Archive. His concerns about the dog-Sherlock were expressed in Animage (May 1983), and here, and elsewhere.

This is what Atsuko Tanaka suggested in her section of Collection of Memorial Texts for Yoshifumi Kondo (近藤喜文さん追悼文集).

Three-dimensionality came up in this roundtable talk.

The quote comes from Katabuchi on Twitter. He also discussed Miyazaki’s reliance on Takahata in this column.

See Cineforum 503 (2011).

This is according to the book Vita da cartoni.

Miyazaki shared this in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Watercolor Impressions.

For commentary about Miyazaki’s old-fashioned filmmaking, see here and The Art of Holmes. Per the latter:

One of the characteristics of Miyazaki anime is the rebirth of manga eiga in a modern context ... Many of the gags in Holmes are classic and traditional, using techniques that do not often appear in current TV anime (because they are thought to be dated).

The reasons for and timeline of the collapse of Sherlock Hound are a little murky, but Katabuchi clarified them on Twitter here and here.

As an aside, Katabuchi’s also revealed that Miyazaki wasn’t the true director of the two half-produced episodes, Mrs. Hudson Is Taken Hostage and The White Cliffs of Dover, despite having storyboarded them. His teammate Nobuo Tomizawa oversaw those.

The quote comes from Animage (June 1983).

See this article from Anime Style.

Katabuchi related this story in his Anime Style column.

For details on the revival of Sherlock Hound, see Animage (November 1984 and May 1985) and Monthly Out (January 1985).

Happy New Year! Glad to have you guys back! Missed your articles!

Whew! And what an inspirational read! It just goes to show you that you shouldn’t always underestimate the opportunities presented to you, even if it seems like nothing much will come of them. You never know, you could end up with the next big thing that inspires future generations, just like Cagliostro and Sherlock Hound!

Once again, thank you!

Adore this show, got it in disc boxset the moment I was aware of it's existence being a fan of both Miyazaki and Sherlock. It's so wonderful and fun!