Welcome! We’re back with a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our slate today:

1) Videos of greats practicing their crafts.

2) China brings the year’s first animated box-office smash.

3) Animation newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – Five treasures

Few sights mesmerize like a great artist or artisan at work. Watching a master glassblower is something special. The same goes for footage of Kandinsky painting, or comic artist Alberto Breccia inking with a razorblade.

It’s in the casual deftness, the lifetime of experience that each movement reveals. It’s in the feeling that human hands, maybe your hands, can do these things. And it’s in the details: all the tiny decisions that get clearer the closer you look. Even if the person doesn’t explain their process, you can see it, and begin to understand how they think.

Until cameras, all of that had to be experienced in person. We’ll never get to watch Michelangelo sculpt. Animation, though, is lucky: many of the best artists ever to work in it have been captured on film.

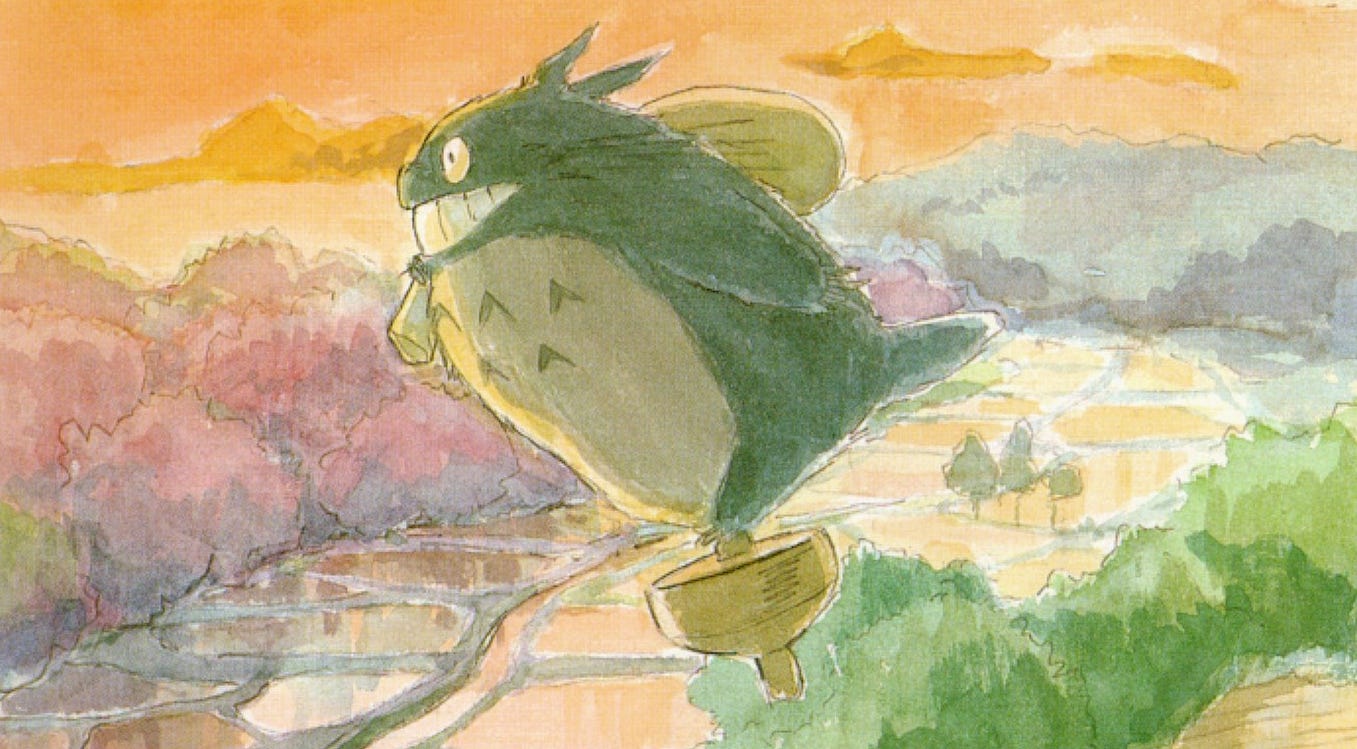

This footage is precious, but sometimes obscure. For that reason, today, we’ve brought together a few standout videos of animation masters painting, drawing and more. The first: a 45-second clip of Hayao Miyazaki with his watercolors.

1.1 – Miyazaki paints

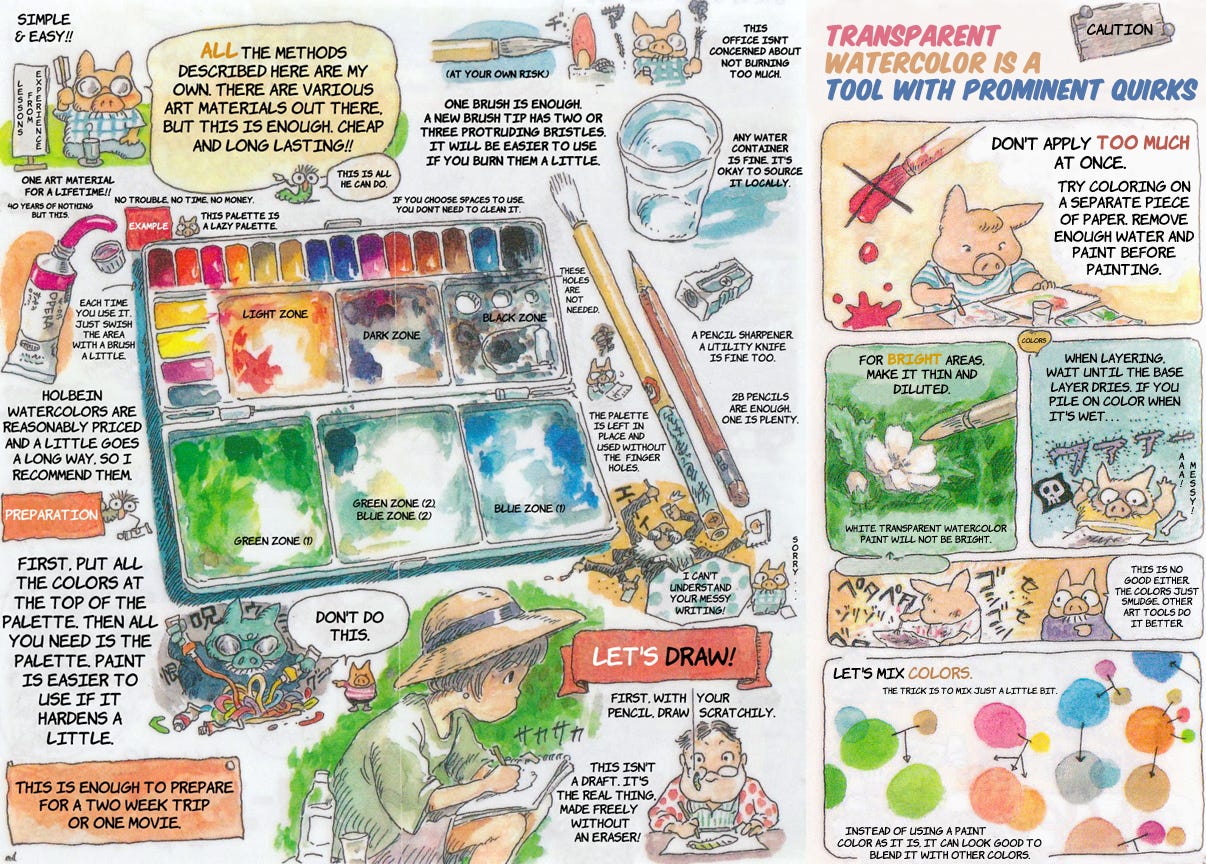

Miyazaki’s watercolor sketches are one of his signatures, and you’ve probably seen them before. He creates them quickly and roughly — it’s been his way since the ‘60s.

When he visualizes his ideas in “image boards” (concept art), he’s not looking for perfection. He uses inexpensive Holbein paints and the tools at hand. Per an article published in the ‘90s, he “grabs whatever paper they have” in the background department and “borrows some worn-out old brushes” to get started.1

The results are beautiful, and beautifully flawed. Here’s what Miyazaki once said about his method:

At the studio we’re always overwhelmed by deadlines, so the idea is not to spend an infinite amount of time creating these things, but to do them as quickly as possible. It’s a totally different approach than most people use when painting with transparent watercolors. In what is completely my own style of doing things, I first draw in pencil, and then quickly trace over that with watercolor, all while trying to render as many images as possible, with as little effort as possible [laughs], as fast as possible. …

A good watercolor painting is not determined by the number of paint colors you have. I once bought a really big palette, but then I always got lost trying to figure out where each color was. After using the same palette for over ten years, with each color always in the same place, my hand now goes to the right color without even thinking about it. …

With watercolors, once you apply them, there’s no way to make corrections, so I use really diluted colors on first brush, and then while painting other areas, if I notice something is too faint, I’ll go back and apply more paint. If I make a mistake I apply white and paint over it, but that totally changes the color, so that when we go to the printer I’m always in a state of despair.

The above clip aired back in 1999, on the British program Dope Sheet. You see Miyazaki’s breezy, imprecise style: he even allows the page to shift and buckle under his brush. He’d been refining his approach since Horus: Prince of the Sun (1968), around 30 years earlier, and you can tell.2

He continued to refine it after this point. Miyazaki speaks in the video about choosing to retire, losing his concentration, feeling his body shut down — he’s almost 60 here. Yet his biggest success was ahead of him.

Spirited Away hadn’t been made. There was no Howl’s Moving Castle or The Boy and the Heron. And those films (and more) would begin with Miyazaki’s watercolor sketches — with the effortless lines and brushstrokes he’d developed over decades.

1.2 – Jiří Trnka creates

In 2025, Jiří Trnka is something of an unknown. Even so, it’s not that much of a stretch to call him the Miyazaki of his own time. From the mid-1940s through the ‘60s, he was a creative leader in animation. Trnka was a Czech who lived behind the Iron Curtain, but artists around the world idolized, visited and copied him.

We published an introduction to his work last year. Trnka’s modernist cartoons, and his stop-motion films like The Hand (1965), changed things. During the ‘50s, a French director wrote about the studio UPA, which was revolutionizing animation at that time. He called it “the most advanced cartoon production center in the world, except for the Trnka team in Czechoslovakia.”3

Trnka was an illustrator, puppet-maker, painter and more. All of those talents appear in the three-and-a-half minutes of footage above, filmed in the ‘50s.4 We see him sketch a character design and a storyboard, create a puppet’s face, paint scenery. His hand is free and relaxed one minute, precise the next. He’s only in his 40s here, but his mastery is obvious.

“Trnka draws with the facility of Picasso; images and characters appear on the paper without hesitation, already seen as it were,” wrote one critic in 1959. “His shooting script for a film is a great picture book.”5

When Trnka worked, people would gather. His animator Vlasta Pospíšilová recalled:

The cameraman lit the scene for him, [Trnka] came and waited, and around him and behind him stood a crowd of people in awe, watching him create. They were people not only from the studio, but also from elsewhere. For me, he was the biggest personality that marked my life. Creative and personal strength emanated from him.6

That lion-like presence of Trnka’s comes through in the footage. Although few alive now saw him create in person, we’re fortunate that a little of the magic was recorded for posterity. Even on film, it’s hard to look away.

1.3 – Lotte Reiniger gives life to paper

Trnka isn’t the only hero of 20th century animation who’s obscure in the present. Lotte Reiniger (1899–1981) of Germany stands with him.

She was one of the first great animators. Reiniger started in the 1910s — her Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) is the oldest animated feature that survives today. Next year is its hundredth birthday.

That earliness makes Reiniger a bit niche: animation from the ‘10s and ‘20s isn’t popular anymore. Still, it’s a mistake to overlook her. Reiniger’s technique — cutout silhouettes animated in stop motion — is a timeless one, and she was a genius at it.

In 1970, a short documentary captured Reiniger’s whole process, from storyboard to design to animation. It’s embedded above. She was around her early 70s, and her scissors move with complete certainty through the paper. Then we see her creations jump to life under the camera.

It’s a vibrant, jittering life that few can match — all focused on character, rather than technical cleanliness. You find it in films like Achmed and Papageno (1935), and in the many she did later.

Across her life, Reiniger worked in this one way: the documentary shows us an animator who’d already spent 50-plus years moving in a single direction. She was an artist out of time, in the sense that she chased the best ideas of early movies long after they became unfashionable. As she once said:

In the days of the silent film the cinema set out to tell its stories by movement alone, and the good film actor invented his own rhythm and was loved for it. Those unforgettable steps of Chaplin which he used for walking into and out of his films were one of the greatest inventions of this phase of the cinema which has passed away only too quickly, becoming one of the lost arts. ... And all the other artists who discovered and developed the voices of their bodies — why have they had to disappear with the coming of sound?7

In our time, many see stop motion as the slowest, most laborious type of animation. Reiniger didn’t operate that way, as the documentary shows. She moved her characters boldly, even improvisationally, and allowed them to work with her. Reiniger wrote in the ‘50s:

People often say to me: “But this must be terribly boring!” On the contrary, it is most exciting. For you must not make a single mistake during that manipulation, however many figures you may have on the set; you must work with great concentration and have your wits about you all the time.

The main thing is to have a well-built-up movement in your figure; then the figure itself gives you the most pleasant surprises during the shooting, displaying unexpected possibilities. It is not a mechanical process at all, like the photographing of a pile of drawings, as is done for cartoons. Another thrilling fact is that during the shooting you never see the movement itself; you can only guess by experience how far your intentions will be carried out.8

Thanks to the documentary, we can see Reiniger’s characters as she saw them: paper puppets, shifting from one lively pose to the next. It offers a new perspective on this one-of-a-kind animator.

1.4 – Osbert Parker’s moving collage

Osbert Parker is the youngest artist on our list today. He’s a British animator, born in the ‘60s and active since the ‘80s, whose work is hard to summarize. Stop motion is his main thing — but he uses it in his own way.

He makes messes and invents. In the ‘90s, he did ads for Nike, Coca-Cola and Budweiser — mind-boggling collages of magazines and shoelaces and chalk. Some of his personal projects, like Film Noir (2006), star people cut frame by frame out of live-action movies. Looking at this stuff, you wonder how it can exist.

In his words:

A lot of directors are known by their style. I hope I won’t ever be associated with one. I always try for something a little new. Sometimes it doesn’t work out as well as I hoped, but it’s important to always keep evolving the work. …

I like the spontaneity of scissors. I like the rough edges and the naivete of the process. It’s not just about the outcome; it’s the process. You make a cut and it suggests something else which goes on to suggest another idea. It’s like children and their wonderfully uninhibited imagination. They don’t use rulers and straight edges to communicate beautiful things. Some of the best things come from accidents and mistakes.9

In the footage above, we find Parker on the set of Yours Truly (2006), one of his stranger experiments. Cutout frames of Humphrey Bogart animate behind the wheel of a toy car, with cops in pursuit. Flat frames of a mid-century woman move in a kitchen, itself assembled from odds and ends. Parker is, very visibly, in his element.

This is play, and few have pursued it as consistently or as masterfully in animation. Recent Parker projects like Scala!!! Programmes and High Street Repeat show that he’s still playing. “I would advise anyone that’s interested in animation, or in art, to just do it,” he’s said. He tells people to make their own messes and find inspiration in them. Watching him work, it’s an easy idea to get behind.

1.5 – Four Disney artists and a tree

Today’s last entry is a video we discovered a few months ago, thanks to writer Alex Dudok de Wit. He covered it at length in Move Madly, his newsletter — always a thoughtful, fascinating read.

This one comes from the ‘50s, and its premise is simple: four artists from Disney take their canvases outdoors and paint one tree, each in their own way. Among them are Eyvind Earle and Walt Peregoy, the artists who defined the looks of Sleeping Beauty and One Hundred and One Dalmatians (respectively), and Marc Davis of the Nine Old Men. We watch them paint, and listen to them explain their thoughts.

Like de Wit wrote:

Peregoy, who spiced Disney features of the era with his bold modernist artwork, here produces a characteristically abstracted and angular image. Davis, one of the great character animators in Disney history, comes up with something more grounded but also simplified, and very readable through its stark contrast. There is a more delicate interplay of light and shadow in [Joshua] Meador’s painting, as we might expect from the effects animator who conjured up the fairy dust in Sleeping Beauty. Earle, a painter with a remarkable feel for trees, focuses this time on the trunk, rendering its gnarled sinews in exquisite detail.

Disney TV broadcasts of the ‘50s often had a degree of squareness or phoniness to them, and this documentary is no exception (de Wit wrote that Walt Disney was “in full avuncular mode” here). But the value of it is undeniable. We’re shown not one but four top artists — in their prime — painting and talking process.

It’s a reminder, again, that animation is a lucky medium. The Disney studio thought to film, televise and archive these moments almost 70 years ago, and now we have them. We get to watch these artists, none of whom are with us anymore, and understand a little better how they did what they did. And it’s mesmerizing.

2 – Worldwide animation news

2.1 – Nezha 2 booms

Somehow, it’s happening again.

To date, China’s biggest animated film is Nezha (2019), a CG adventure rooted in myth. Its lead is a demonic troublemaker, Nezha himself, who becomes a hero. Viewers loved it — the film earned over $700 million in China. Its director, Jiaozi, came from the indie scene: he taught himself animation while living with his mother, then broke out with See Through (2008). Nezha turned him into a star filmmaker.

A sequel was inevitable. And this week, amid lots of hype, Jiaozi brought Nezha 2 to theaters. They were reportedly packed. The film’s first-day returns: 473 million yuan (around $65.8 million). Its five-day opening: above $430 million. For reference, that’s nearly double Moana 2’s domestic opening last year.

Now, forecasters say that it’s “only a matter of time” before Nezha 2 topples China’s highest-grossing movie, The Battle at Lake Changjin (2021). In fact, Deadline reports that it might become “the first movie to ever gross $1B in a single market.”

Nezha 2 took around five years and a team more than 4,000 strong, according to producer Wang Jing. Its budget was upward of 500 million yuan (over $69 million) — a massive sum for a Chinese film, but modest by Hollywood standards.

Yet the project’s size, hype and successful predecessor don’t explain its popularity alone. There’s another factor: as with the first film, viewers really, really like it. Just check Douban (think a mainstream Letterboxd). Its users are famously harsh, especially toward Chinese animation, but Nezha 2 is currently rated 8.5 out of 10 there.

Given all that, a third Nezha is guaranteed — and Jiaozi intends to take his time with it. The second one demanded a year or two more than planned, but the team wanted to do it right. “We’re in the animation business as a lifelong endeavor,” he told the press, “not to make quick money.”

2.2 – Newsbits

Speaking of China, it looks like Chang’an (2023) is coming westward at last, with screenings in Ireland and Britain later this month. It’s a well-regarded hit in China, but hard to see abroad.

In Russia, artist Francheska Yarbusova is suing the Central Bank over its use of her hedgehog character (the one from Yuri Norstein’s Hedgehog in the Fog) on a commemorative coin.

A cult French film, Gwen and the Book of Sand, is getting an English Blu-ray release by the ever-excellent Deaf Crocodile. It’s been restored, and the trailer is gorgeous.

Also from France: the César nominees were announced. Among them are Flow and The Most Precious of Cargoes, the latter by Michel Hazanavicius (The Artist).

In America, Common Side Effects has arrived on Adult Swim, and there’s reason to pay attention. Co-creator Joe Bennett was behind Scavengers Reign, and he notes that many “of the same artists that worked on that show also contributed” here.

British animator Tony White has published a memoir, Animation Me. It gets into his long career, including his time with Richard Williams. Find an excerpt via White’s newsletter. (Also, we put out a two-part interview with him last year.)

In America, Dog Man made $36 million this weekend.

One more French story. There’s a preview clip of The Little Run, by the people behind the wonderful Shooom’s Odyssey (2019), and it’s very much worth a look.

Mfinda, animated in Japan but drawn from Congolese stories, has a strong new promo image. Gisaburo Sugii (Night on the Galactic Railroad) is co-directing this one.

On that note, we explored the making of Night on the Galactic Railroad, one of our favorite anime films.

Until next time!

From Starting Point 1979–1996 (“The Pictures Are Already Moving Inside My Head”), the source for Miyazaki’s quotes today.

Miyazaki spoke about the origins of his image board practice in Hayao Miyazaki Image Board (1983).

This is Chris Marker (La Jetée) in the essay “Cinéma d'Animation: UPA,” published in Cinéma 53 à travers le monde.

The clips of Trnka come from the documentary Loutky Jiřího Trnky (1956), included in the Artus edition of Old Czech Legends.

The words of Bernard Orna in the article “A Dream of Puppets,” published in The Puppet Master (July 1959).

From Reiniger’s interview in Life and Letters Today (Spring 1936).

See the profile on Parker in Communication Arts (March/April 1996).

Solid Gold…again(duh)! I am always blown away by your Substacks! Lots of info, well organized, fun to read, and Animation! I do not have the capability to be a monthly subscriber, but is there a way to send a gift now and then? (monetary, cup of coffee, etc.)

These really are treasures you’ve shared— incredible views into how these artists work. It’s always fascinating and instructive to see what different types of shorthand people develop over time. Thank you!