Happy Thursday! As June nears its end, we’re wrapping up a half-year of Animation Obsessive. It’s been quite a ride.

This newsletter began in February 2021. Since then, we’ve refined a process that gets issues done on schedule, twice a week. We know it well — and yet each year brings new questions. One of 2024’s biggest questions has been, “How do we keep this project both fresh and accessible after three years?”

Only readers can say for sure whether we’ve succeeded, but we’ve done our best to nail that balance since January — across more than 45 issues. Through our widening research, we’ve gotten to tell animation stories from France, China, India, South Africa, Armenia and beyond. And we’ve come at this work from angles we haven’t before.

With July almost here, now feels like a good time to glance back at the past months: what we’ve discovered, what’s resonated and what trends have been lying beneath the surface of the newsletter.

Big articles

In 2024, a few issues have outdone the rest. But one stands as our most viewed of the year: Selling Ghost in the Shell.

That one, published in May, was a bit of a curveball. It tells the story of Ghost in the Shell (1995) not so much through its production, but through the financial reasons for its existence — and the success it had on video. The film was bankrolled (partly by a Western company) in an attempt to sell anime to the West. And it worked.

This piece got an amazing response. Historian Helen McCarthy called it “really excellent” (an honor) and we noticed a lot of discussion on Hacker News. In terms of traffic, it rose into our top five ever. We’re grateful for all the positivity.

Another May issue that drew extra notice, When Katsuhiro Otomo Learned, focused on The Order to Stop Construction (1987). We began our hunt for research material on this film in 2021. Thanks to animator Justin R. Hamrick, we finally found enough.

Hamrick showed us a rare essay in which Otomo admitted to watching Thieves Love the Peace (a Miyazaki episode of Lupin the 3rd) again and again on VHS. Its influence seeped into not just Construction but much of Otomo’s future work. Even the Akira bike slide kind of resembles a moment from this episode. Like Otomo wrote:

I think it’s fair to say that I learned a considerable part of how to create animation from this video, such as the number of shots (katto-su) and the cinematography and editing (katto-wari).

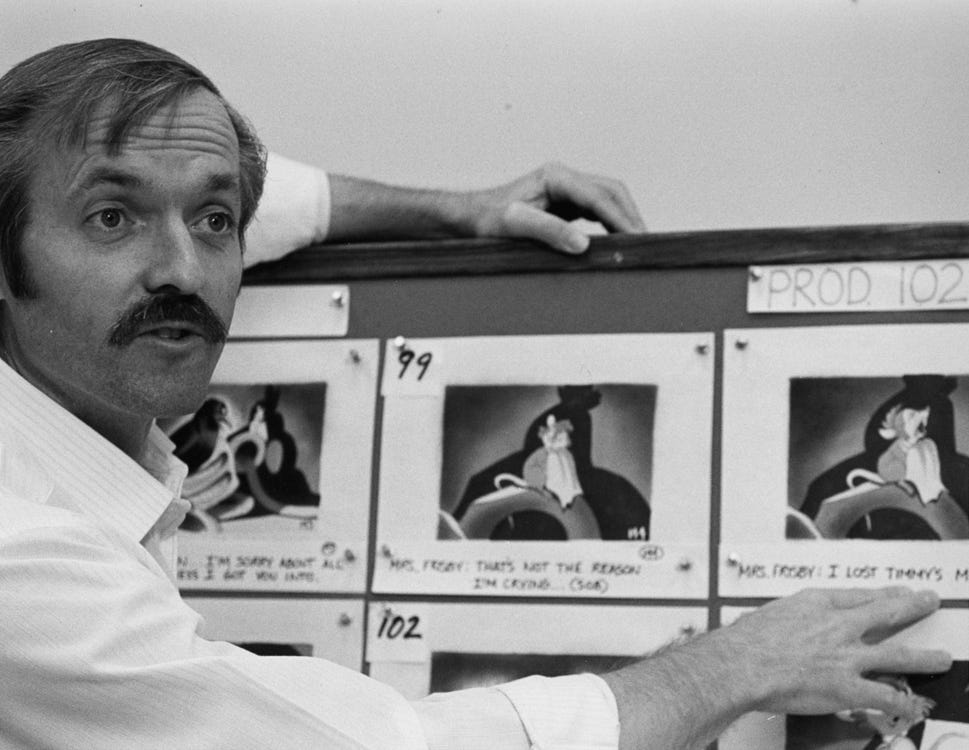

Not all of our big articles were anime-related, though. Rewinding to April, we have the trilogy about Don Bluth. It began with Don Bluth’s Garage Band, continued with The Process of NIMH and wound to a close with Not Living by Animation Alone.

After the popularity of the garage story, it felt like the right time to cover The Secret of NIMH — a years-old idea, always too large and scary to do. That fear turned out to be justified: long hours went into researching and writing the NIMH piece. Still, we’re really happy with it, and with the wonderful comments it received.

The Bluth series runs from his time at Disney in the ‘70s through his breakaway to create NIMH. It’s the tale of an artistic dispute. The Disney studio had fallen victim to “a kind of key-animator supremacism,” we wrote. Animators’ work was valued above all else, and many other elements of classic Disney filmmaking and storytelling were falling away. Bluth tried to save them — and he did. Soon, Disney itself followed suit.

Trends of the year so far

Speaking of Disney, it’s been a tricky subject for us in the past. After thousands of other articles and books, what’s left to say? In 2024, though, we’ve found a few angles — and the studio has shown up a lot in the newsletter, even beyond the Bluth pieces.

Setting the Stage for Mulan (for everyone) and Surviving Disney (for members) are two highlights. The first analyzes the production design of Mulan and includes its style guides in PDF form. In the second, we looked into the troubled time that Oskar Fischinger, a German animator, spent on Fantasia (1940). Disney nearly broke him, but he did important work at the studio. Per historian William Moritz:

Oskar brought prints of his films, which were screened every week for nine months for the entire Disney staff during lunch and breaks. Thus Oskar’s influence at Disney was pervasive, spilling over on to other films like Dumbo, the South American features and Pinocchio, for which Oskar actually animated the Blue Fairy’s magic wand.1

The one about Mulan’s production design landed in a second trend, too, besides Disney: technical analysis of filmmaking and animation. Two other favorites in this vein were Animation Without Movement and Miyazaki, Disney and Eisenstein, for members.

Those are sister articles, and they tie back to our older piece about Miyazaki’s use of time and space. Both also involve Disney. One follows the rise of stillness in animation — a break with Disney’s style that opened up new storytelling possibilities for UPA, Osamu Dezaki, Studio Ghibli and more. In the other, we explored the filmmaking differences between Disney and Miyazaki, how his staging got into Disney’s latter-day work and how the two styles differ from montage. As we wrote:

In Cagliostro, space is absolute. The characters look cartoony, but they inhabit a world that exists in three dimensions. Miyazaki’s camera choices, even during simple conversation scenes, put us right there with the characters in space. He stages shots almost like they weren’t drawn — like he was picking angles in physical locations as a scene played out in real time.

The Rescuers tends to take a different approach. Animation is the star here, and the filmmaking is designed around it. The team often trades an intimate sense of space for flatter staging, which allows the characters’ complex movements to read.

All that said, our main trend of 2024 might be our informal series on animation behind the Iron Curtain. It started in January and is still ongoing.

These stories can get niche — like the one about Fleischer employee Lucille Cramer, who helped to industrialize animation in Moscow during the ‘30s. But we’re proud of that piece and the ground it broke. The same goes for many of its siblings.

Among these are Beaten by Beginners and Moscow to Tokyo, Tokyo to Moscow. The first tackles the defeat of paint animator Alexander Petrov at the 1990 Oscars — the second, the impact of Soviet animation on Japan, and vice versa. The one about Robert Sahakyants, a Soviet Armenian hippie and rebellious innovator, we also found rewarding.

Rounding out this semi-series is a trio of issues dedicated to Jiří Trnka — the genius from communist Czechoslovakia. In particular, our public article The Grandmaster of Stop Motion is one of our favorites to date.

Outliers

But many issues from 2024 haven’t fallen cleanly into these trends or series. We like to keep Animation Obsessive’s topics a little scattershot, and we’ve been lucky to tell a number of out-of-the-way stories that (as with the Trnka piece) stand with our favorites.

A few more include:

The Nominee You Didn’t See — on the beautiful Funny Birds (2021).

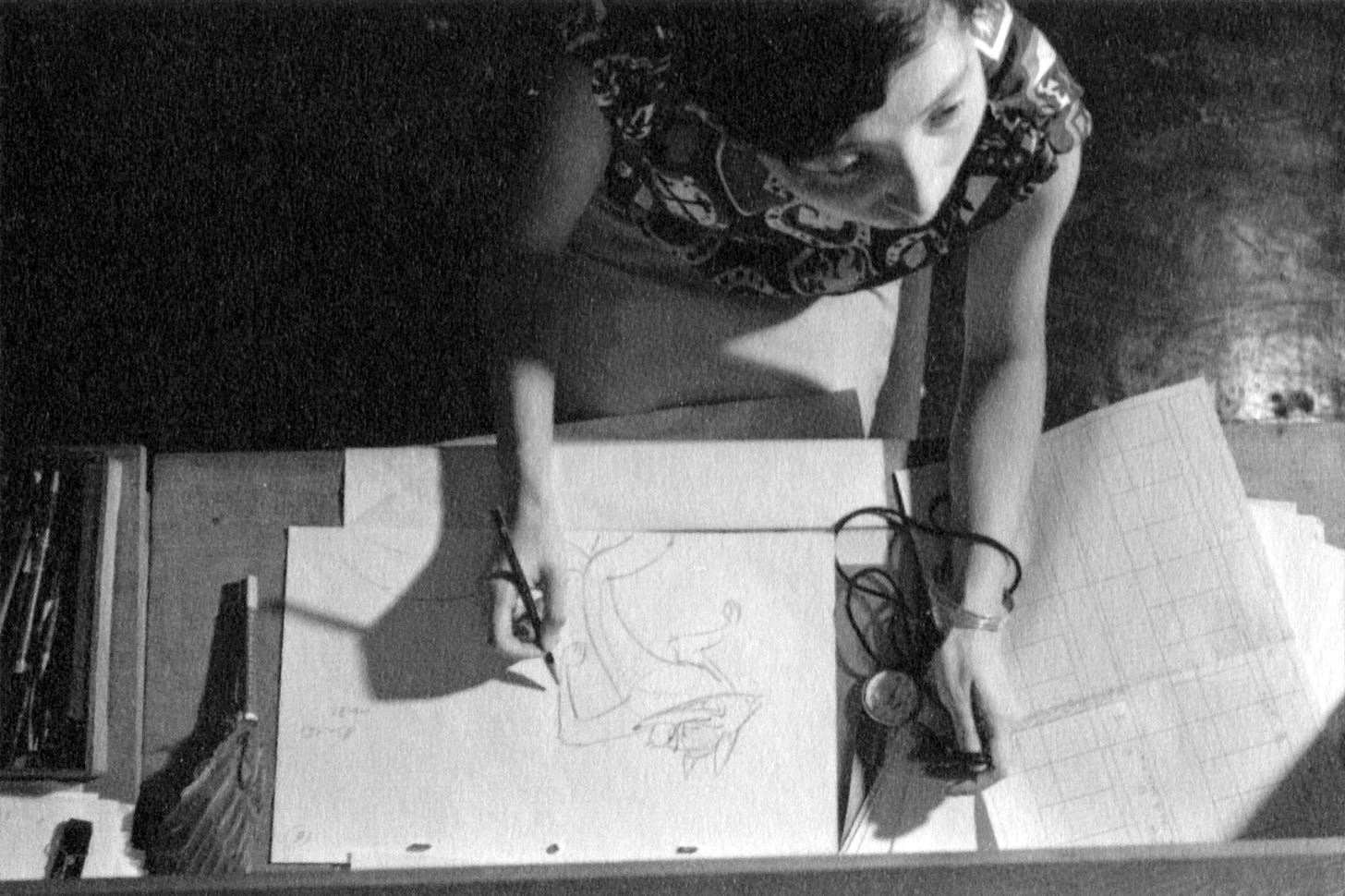

Reiko Okuyama, Commercial Artist — our tribute to one of Japan’s great animators.

“Simple, Clear and Appealing” — a story of cel animation.

In China, Behind the Camera — about camera operator Duan Xiaoxuan.

The Making of Chie the Brat — on Isao Takahata’s underrated feature.

Stick Fights — the hidden history of the Flash series Xiao Xiao.

Pivoting and Making It Work — a deep dive into The Big City by Ed Bell.

Seeing Music — on Suzie Templeton’s Peter and the Wolf (2006).

The Origin of a Master Painter — regarding the early career of Nizo Yamamoto.

Writing Teen Titans — inside the mechanics of screenwriting.

“Pleasurable Hell” and Leaving the “Monastery” — our two-part interview with British animator Tony White.

2024, part two

As the year’s second half approaches, we’ve got quite a bit planned. Some of it is already close to done — just awaiting final tweaks and approvals. Other projects, though, will need more time and attention than most.

On that note, we’re starting our usual mid-year break today. We’ll be back with a new issue next month — July 28.

Like always, this is a working vacation. These breaks give us time not just to relax, but to get ready — and to do the research and organization that’s too much to handle on a deadline. After each past break, we’ve come back more prepared than the last time, and more ready to take on the months and years ahead.

Before we go, we have to thank everyone who reads this newsletter — and all the people who’ve sent comments and emails in 2024 so far. Your support often overwhelms us.

We’ve said it before, but we never thought that this newsletter would or could reach so many (over 24,000 now). Getting to do this as a job is a privilege. We’re incredibly grateful — and we’ll return next month with more!

See you again soon!

From Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger.

Oh maaan, I didn’t know about your stupid break. July’s gonna suck! Kidding, but not - little I look forward to as much as Thursday/Sunday’s articles

I am truly fascinated by this newsletter, which has become one of my favorites. And not only for the topic, which has always been fascinating for me and stimulates my creativity to the maximum, but also for the sometimes 'playful' way in which you combine the concrete creation of animations and drawings with insights, background and analysis, all always in a 'juicy' way. Furthermore, I think these recapitulation issues are very important and you have probably inspired me for one in the near future regarding the many papers I talk about in my newsletter. Thanks for sharing.